Vaccine efficacy2,3

Vaccine efficacy measures how the vaccine performs under ideal circumstances in a regimented protocol in relatively normal hosts – likely the best-case-scenario benefit. Vaccine efficacy is the percent difference in confirmed influenza episodes in vaccinees getting the “experimental” vaccine vs. episodes in nonvaccinees (or vaccinees getting an established vaccine). Vaccine efficacy, therefore, is usually calculated based on prospective well-controlled studies under ideal circumstances in subjects who received their vaccines on time per the recommended schedule. Most such studies are performed on otherwise healthy children or adults, with most comorbidities excluded. The “experimental” vaccine is generally from a single manufacturer from a single lot, and chain-of-custody is well controlled. The vaccine is administered at selected research sites according to a strict protocol; vaccine storage is ensured to be as recommended.

Confidence intervals

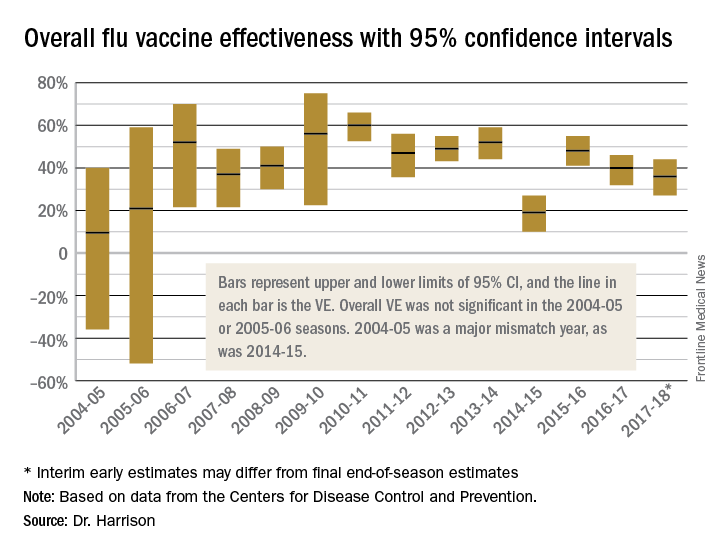

To assess whether the “protection” is “significant,” the calculations derive 95% confidence intervals (CI). If the 95% CI range is wide, such as many tens of percents, then there is less confidence that the calculation is correct. And if the lower CI is less than 0, then the result is not significant. For example, a VE of 20% is not highly protective, but can be significant if the 95% CI ranges from 10 to 28 (the lower value of 10 is above zero). It would not be significant if the 95% CI lower limit was –10. Values for seasons 2004-2005 and 2005-2006 were similar to this. Consider however that a VE of 55% seems great, but may not be significant if the 95% CI range is –20 to 89 (the lower value is less than zero). In the ideal world, the VE would be greater than 50% and the 95% CI range would be tight with the lower CI value far above zero; for example, VE of 70% with 95% CI ranging from 60 to 80. The 2010-2011 season was close to this.

Type and age-specific VE

Aside from overall VE, there are subset analyses that can be revealing. This year there are the concerning mid-season VE estimates of approximately 25% for the United States and 17% in Canada, for one specific type, H3N2, which unfortunately has been the dominant circulating U.S. type. That number is what everybody seems to have focused on. But remember influenza B becomes dominant late in most seasons (increasing at the time of writing this article). Interim 2017-2018 VE for influenza B was in the mid 60% range, making the box plot near 40% overall.

Age-related VE analysis can show difference; for example, the best benefit for H3N2 this season has been in young children and the worst in elderly and 9- to 17-year-olds.

Take-home message

The simplest way to think of overall VE is that it is the real-world, worst-case-scenario value for influenza protection by vaccine against the several circulating types of influenza.

While this year’s vaccine seems less protective than we hoped, we should still feel good recommending a vaccine that can prevent 40% of overall influenza cases and that provides an additional benefit of lessening severity in many breakthrough infections. That said, we still need a better and universal influenza vaccine.Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. Children’s Mercy Hospital receives grant funding for Dr. Harrison’s work as an investigator from GSK for MMR and rotavirus vaccine studies, from Merck for in vitro and clinical antibiotic studies, from Allergan for clinical antibiotic studies, from Pfizer for pneumococcal seroepidemiology studies, and from Regeneron for RSV studies. Dr. Harrison received support for travel and to present seroepidemiology data at one meeting. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. MMWR Weekly. 2017 Feb 17;66(6):167-71.