The provision of home-based ventilatory support has been the purview of the pulmonologist for more than 50 years. Before the birth of sleep medicine as a dedicated specialty, the focus of home ventilation was on the care of patients with neuromuscular disease (NMD), who were required to use full-sized mechanical ventilators, nonvented masks, and bulky tubing sets with double-lumen active circuits served by an external pressure line, since this was the only equipment available at the time. These large devices were cumbersome and limiting in their lack of portability but were well suited to the needs of patients with NMD. They used volume-cycled ventilation, ensuring full ventilatory support with a guaranteed inspiratory time and respiratory rate. Although effective, they lacked many of the conveniences that are now the norm, including integrated humidifiers and a wide range of mask options.

In the 1980s, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) became widely available as therapy for OSA (Shepard et al. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2005;1[1]:61). The large number of patients with OSA spawned a revolution in home respiratory therapy, driven by a rapid expansion in resources, including the development of outpatient facilities dedicated to diagnosing and treating sleep-related breathing disorders, smaller and lighter equipment with novel ventilator modes, improved options for facial appliances, and other comfort-oriented features. While a new generation of practitioners pursued training in the management of sleep-disordered breathing, it was largely focused on OSA, with very limited experience managing the special needs of the NMD patient population.

Sleep laboratories often lacked the necessary amenities and frequently performed inappropriate diagnostic studies that delayed the time to initiation of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) (Boitano and Benditt. Respir. Care 2011;56[6]: 878). Titration studies were often performed without defined protocols that would guarantee adequate patient ventilation; the first such protocol for sleep labs to use as a guide to titrating patients with NMD was not published until 2010. (Berry et al. J Clin. Sleep Med. 2010;6[5]:491).

In addition to the issues related to a lack of resources, there were other barriers delaying the marriage between sleep medicine and these patients. For example, although the American Academy of Neurology recommends the use of NIV as standard of care for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, they do not recommend the involvement of a sleep laboratory, choosing instead to rely upon guidance from pulmonary function testing (Miller et al. Neurology. 2009;739[15]:1218). This recommendation is based on several studies, including a prominent randomized control trial, which demonstrated a mortality and quality of life benefit from NIV, though it did not use polysomnography to optimize the treatment (Bourke et al. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5[2]:140). For years, many clinicians caring for NMD patients avoided referring them to sleep programs, trying to provide care with minimal support from pulmonary physicians. In a survey of Muscular Dystrophy Association clinics from 2000, polysomnography was only provided by a third of programs; the authors subsequently call the procedure unnecessary, as well as "uncomfortable and often painful" (Bach and Chaudhry. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2000;79[2]:193).

Advances in sleep medicine therapeutics

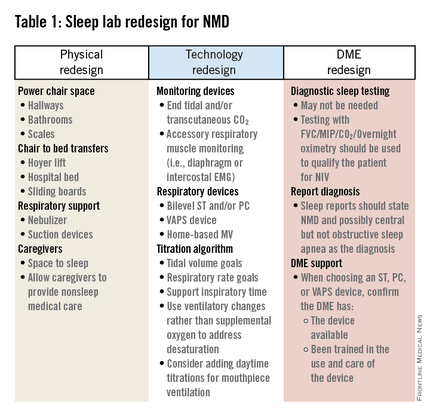

New developments seem likely to bring these previously discordant groups into a more harmonious relationship, driven by changes on two fronts. First, the role of the sleep lab is changing, as home sleep testing combined with auto-titrating CPAP machines play a larger role in the management of OSA. For brick-and-mortar labs needing to reinvent themselves, one option is to expand care to aggressively address the needs of those with non-OSA forms of sleep-disordered breathing, including nocturnal hypoventilation due to NMD. Though less prevalent, these conditions will continue to require in-lab sleep testing, although labs will need to adapt to meet the additional needs of these patients, as outlined in Table 1. The physical design of the lab will need to better accommodate power chairs, with additional space for caregivers. Polysomnographic technologists will need to have equipment to facilitate bed-to-chair transfers. Respiratory assist device options will need to be expanded to include those more capable of supporting ventilation, while study montages will need to include parameters to better assess ventilation, work of breathing, and/or accessory muscle use. Lastly, labs will need to develop more productive relationships with durable medical equipment providers to help them understand that patients with NMD have different needs than those with OSA.

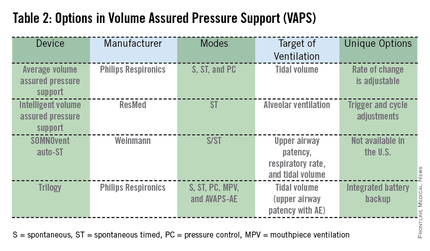

The second major development that may allow sleep providers to better service these patients is the advent of new technology for home-based ventilation. Many of the advantages previously available only with CPAP devices have now been made available for use with noninvasive ventilators. These new NIV devices are smaller, and use lighter, single-lumen passive circuits that can utilize any of the commonly available CPAP masks instead of requiring a nonvented mask. By eliminating the complex circuitry and limited mask choices of traditional home-based mechanical ventilators and replacing them with systems that are familiar to sleep medicine physicians and durable medical equipment providers, access to care becomes more realistic for all patients with NMD.