Do hospitalists, or anyone who spends time practicing within the hospital setting, feel well equipped to deal with all aspects of an inpatient’s chronic pain? In palliative care, we have training and interest in this field, our program has some resources earmarked for this, and we face chronic pain multiple times a day. Yet, it is difficult to recall a patient encounter in which some piece of the pain plan did not seem bereft of a key element.

Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) data, government agencies and legislation, media, and other avenues call more attention to the escalating problem of the culture and care of chronic pain. And, because the Joint Commission, HCAHPS, and other trackers of pain in the hospital do not distinguish between acute pain and chronic pain, we are challenged with creating approaches to a problem that in many ways is out of our control.

At Seton Medical Center in Austin, Tex., we have proposed and performed a short pilot of a model that allowed us to see where our gaps exist and to think through how to shrink them. Importantly, it made an impression on our leadership to the degree that they are considering a business plan we put forward to make this a permanent part of our institution.

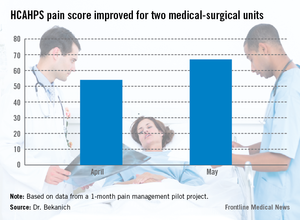

Our pilot project produced data that made us proud as well as demonstrated areas that need improvement. For pain specialties that are hospital based, the response times were excellent. These consults were typically seen within 4 hours of the order being placed. For those specialties that do not have a regular inpatient presence, new consults were often not seen until the next day causing patient frustration. HCAHPS rose during that month (see graphic).

But before exploring the model we have proposed and piloted in conjunction with hospitalists, it is worth examining what we call "pain truths" for chronic pain (CP):

• CP is the most common symptom of many serious or advanced illnesses. While often thought of as a condition associated with cancer, it is now recognized as a part of almost every major illness arising from the failure, or damage to, each major organ. We also have a host of patients with painful conditions that have no clear etiology in areas such as the back, abdomen, and extremities.

• In most cases, CP began long before the patient was hospitalized and has no cure. It is frustrating to be on either side of this equation, because the patient does not always appreciate our limitations, and we can be left feeling less than our best for not being able to solve the problem.

• Hospital operations have not been well equipped to deal with chronic pain. The history of pain control in the hospital is such that we’ve excelled in the perioperative realm and in controlling other forms of acute pain. This is not the case with chronic pain. Whether it is a lack of useful measurements (how helpful is it to use a 10-point pain scale for CP who "feel fine" at a 9 or 10 and rate their pain at 100 out of 10 when they are having an exacerbation?), inadequate access to procedures for CP, or an absence of teams that specialize in tackling it, the number of hospitals fully prepared for CP are indeed few in number.

• No one specialty or provider deals with all facets or forms of pain. This statement frequently elicits surprise. However, no single training tract is available that teaches how to manage medications in medically complex patients, perform procedures, use a variety of counseling techniques, attend to the psychosocial barriers, and improve function via different physical therapies. It takes a diverse team to cover CP from tip to tail.

• The educational and cultural gaps in pain evaluation and management for health care providers are vast. The medical literature is flush with testimonials of this.

• Inpatient incentives for excellence in pain management are evolving from unfavorable to favorable. With reimbursements tied to HCAHPS and readmission, along with a shift toward rewarding value, we have an opportunity to change the balance sheet in resourcing pain teams.

• Comprehensive inpatient management is not possible without a complimentary outpatient component. Without the "safe place to land," patients may as well run into roundabouts that have an equal chance of spilling them out back in the direction of the hospital. These long-term problems need long-term solutions. Frequently, the best we can hope for in the hospital is to deliver a CP patient an experience that highlights the expression of empathy, demonstrates our commitment to continuously trying to help them, and cools off their pain to a tolerable level. The bulk of the work needs to be done outside the hospital walls.