Missed Cervical Spine Injury

| An 83-year-old man presented to the ED via emergency medical services (EMS) with a chief complaint of neck pain. He was the restrained driver of a car that was struck from behind by another vehicle. The patient denied any head injury, loss of consciousness, chest pain, shortness of breath, or abdominal pain. His medical history was significant for hypertension and coronary artery disease, for which he was taking several medications. Regarding his social history, the patient denied alcohol consumption or cigarette smoking. |

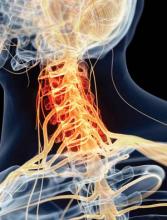

The patient’s physical examination was unremarkable. His vital signs were normal, and there was no obvious external evidence of trauma. The posterior cervical spine was tender to palpation in the midline, but no step-off signs were appreciated. The neurological examination, including strength and sensation in all four extremities, was normal.

Since the patient’s only complaint was neck pain and his physical examination and history were otherwise normal, the emergency physician (EP) ordered radiographs of the cervical spine. The imaging studies were interpreted as showing advanced degenerative changes but no fractures, and the patient was prescribed an analgesic and discharged home.

When the patient woke up the next morning, he was unable to move his extremities, and returned to the same ED via EMS. He was placed in a cervical collar and found to have flaccid extremities on examination. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the cervical spine revealed a transverse fracture through the C6 vertebra. Radiology services also reviewed the cervical spine X-rays from the previous day, noting the presence of fracture.

The patient was taken to the operating room by neurosurgery services but remained paralyzed postoperatively. He never recovered from his injury and died 6 months later. His family sued the EP and the hospital for missed diagnosis of cervical spine fracture at the first ED presentation and the resulting paralysis. The case was settled for $1.3 million prior to trial.

Discussion

The evaluation of suspected cervical spine injury secondary to blunt trauma is a frequent and important skill practiced by EPs. Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of spinal cord injury in the United States (42%), followed by falls (27%), acts of violence (15%), and sports-related injuries (8%).1 A review by Sekon and Fehlings2 showed that 55% of all spinal injuries involve the cervical spine. Interestingly, the majority of cervical spine injuries occur at the upper or lower ends of the cervical spine; C2 vertebral fractures account for 33%, while C6 and C7 vertebral fractures account for approximately 50%.1

There are two commonly used criteria to clinically clear the cervical spine (ie, no imaging studies necessary) in blunt-trauma patients. The first is the National Emergency X-Radiography Use Study (NEXUS), which has a sensitivity of 99.6% of identifying cervical spine fractures.1 According to the NEXUS criteria, no imaging studies are required if: (1) there is no midline cervical spine tenderness; (2) there are no focal neurological deficits; (3) the patient exhibits a normal level of alertness; (4) the patient is not intoxicated; and (5) there is no distracting injury.1

The other set of criteria used to clear the cervical spine is the Canadian Cervical Spine Rule. In these criteria, a patient is considered at very low risk for cervical spine fracture in the following cases: (1) the patient is fully alert with a Glasgow Coma scale of 15; (2) the patient has no high-risk factors (ie, age >65 years, dangerous mechanism of injury, fall greater than five stairs, axial load to the head, high-speed vehicular crash, bicycle or motorcycle crash, or the presence of paresthesias in the extremities); (3) the patient has low-risk factors (eg, simple vehicle crash, sitting position in the ED, ambulatory at any time, delayed onset of neck pain, and the absence of midline cervical tenderness); and (4) the patient can actively rotate his or her neck 45 degrees to the left and to the right. The Canadian group found the above criteria to have 100% sensitivity for predicting the absence of cervical spine injury.1

The patient in this case failed both sets of criteria (ie, presence of cervical spine tenderness and age >65 years) and therefore required imaging. Historically, cervical spine X-ray (three views, anteroposterior, lateral, and odontoid; or five views, three views plus obliques) has been the imaging study of choice for such patients. Unfortunately, however, cervical spine radiographs have severe limitations in identifying spinal injury. In a large retrospective review, Woodring and Lee,3 found that the standard three-view cervical spine series failed to demonstrate 61% of all fractures and 36% of all subluxation and dislocations. Similarly, in a prospective study of 1,006 patients with 72 injuries, Diaz et al,4 found a 52.3% missed fracture rate when five-view radiographs were used to identify cervical spine injury. In addition, radiographic evaluation of elderly patients was found to be even more challenging in identifying cervical spine injury due to age-related degenerative changes.