Emergent Initial Therapy: First-Line Agents

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are the mainstay of emergent treatment for status epilepticus. The choice of benzodiazepine may be dependent on the clinical setting and availability of IV access or other resources. In the United States, diazepam, lorazepam, and midazolam are the common formulations used for abortive emergent initial therapy.

Diazepam. One of the advantages of diazepam is that it is has the advantage of being water soluble at room temperature, which allows rectal rescue kits for home treatment. Although diazepam is efficacious for status epilepticus, variable pharmacokinetics leading to repeat dosing and further sedation make other benzodiazepines safer.

Lorazepam. Generally accepted as the preferred IV formulation for seizure, lorazepam requires refrigeration and has a short shelf life, making its use challenging in the prehospital setting. When administered via the IV route, lorazepam works as rapidly as diazepam in treating seizures but with a longer duration of effectiveness, resulting in a decreased need to re-dose or administer an alternative antiepileptic drug (AED).5

Midazolam. Newer studies suggest that buccal, intranasal, and IM midazolam may be superior to buccal, intranasal, and IM diazepam in treating GCSE.6 The Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial demonstrated IM midazolam to be at least as efficacious as IV lorazepam in the prehospital setting for treating GCSE.2

Efficacy, Route, and Dosing

A meta-analysis of all three benzodiazepines in pediatric patients with seizure showed midazolam to have the highest probability of aborting seizure activity, while lorazepam had the least likelihood of causing respiratory depression.7The authors concluded that IV lorazepam and non-IV midazolam were superior to IV and non-IV diazepam in the treatment of pediatric seizures.7

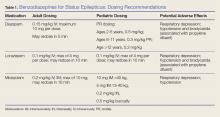

A recent retrospective study that analyzed benzodiazepine use in the emergency setting noted underdosing of benzodiazepines in the ED for nonprotocol-driven treatment of status epilepticus, resulting in the increased potential for adverse outcomes and intubations.8 Table 1 provides benzodiazepine dosing recommendations by route for adult and pediatric patients, along with potential adverse effects.

Adverse Effects

As noted previously, benzodiazepines can cause respiratory depression. Anecdotally, respiratory depression is often related to the rate at which the benzodiazepine is administered. For example, most treatment recommendations advise giving IV lorazepam over a 2-minute time period—not as an IV push.7

With respect to other adverse effects, it is important to note that IV formulations of diazepam and lorazepam contain propylene glycol as a diluent, which may lead to hypotension and bradycardia, especially when large volumes are infused over short periods of time.9

Second-Line Agents

While emergent initial therapy with benzodiazepines is well established, the preferred second-line agent, or urgent control therapy, continues to be a subject of controversy due to a lack of conclusive evidence for a superior agent.10 The Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT) is currently conducting a head-to-head study to determine if any of the commonly used second-line agents (ie, fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid) will prove to be more efficacious.11 Recently, the adult arm of the ESETT trial was halted due to futility.