SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Despite being as common as asthma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often remains undiagnosed and untreated in primary care.1 In brief, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines PTSD as persistent and long-term changes in thoughts or mood following actual or threatened exposure to death, serious injury, or sexual assault that leads to re-experiencing, functional impairment, physiologic stress reactions, and avoidance of thoughts or situations associated with the original trauma.2 More than one in 10 women and one in 20 men experience PTSD in their lifetime.2,3 Population-based studies have not yet determined the prevalence among children.3 Almost 40% of US adults report having experienced a trauma before age 13, and about one-third of these go on to develop PTSD.4

Individuals with PTSD have higher rates of somatic complaints, overall medical utilization, prescription use, physical and social disability, attempted suicide, and all-cause mortality.3,5-7 PTSD is associated with increased risk for cardiac, gastrointestinal, metabolic, and immunologic illnesses, other psychiatric illnesses, risky health behaviors, and decreased medical adherence.4,6 Additionally, prevention and treatment efforts for STDs and obesity are less effective among those with trauma histories.4 Thus, detection and treatment of PTSD improves the likelihood of successfully treating other health concerns.

THE ESSENTIALS OF A PTSD DIAGNOSIS

DSM-5 diagnosis of PTSD requires the experience of a trauma and resultant symptoms from each of 4 symptom-clusters:2

- one or more re-experiencing symptoms (eg, intrusive memories or recurrent distressing dreams, psychological distress or physiologic reactions to reminders of the trauma)

- one or more avoidance symptoms (eg, avoidance of trauma memories or of people and places that trigger a reminder of the trauma)

- two or more changes in thoughts or mood (eg, negative beliefs about self or others, social detachment, anhedonia)

- two or more changes in arousal activity (eg, sleep problems, hypervigilance, inability to concentrate).

Since many people experiencing traumas do not develop PTSD,5,8 symptoms must last at least one month to meet the criteria for diagnosis.2 Sexual trauma, experiencing multiple traumas, and lack of social support increase the risk that an individual will develop PTSD.9-11 Notably, symptom onset will be delayed 6 months or more in some individuals,2,8 making it more difficult for those patients and clinicians to connect symptoms to the trauma.12

Differential diagnosis

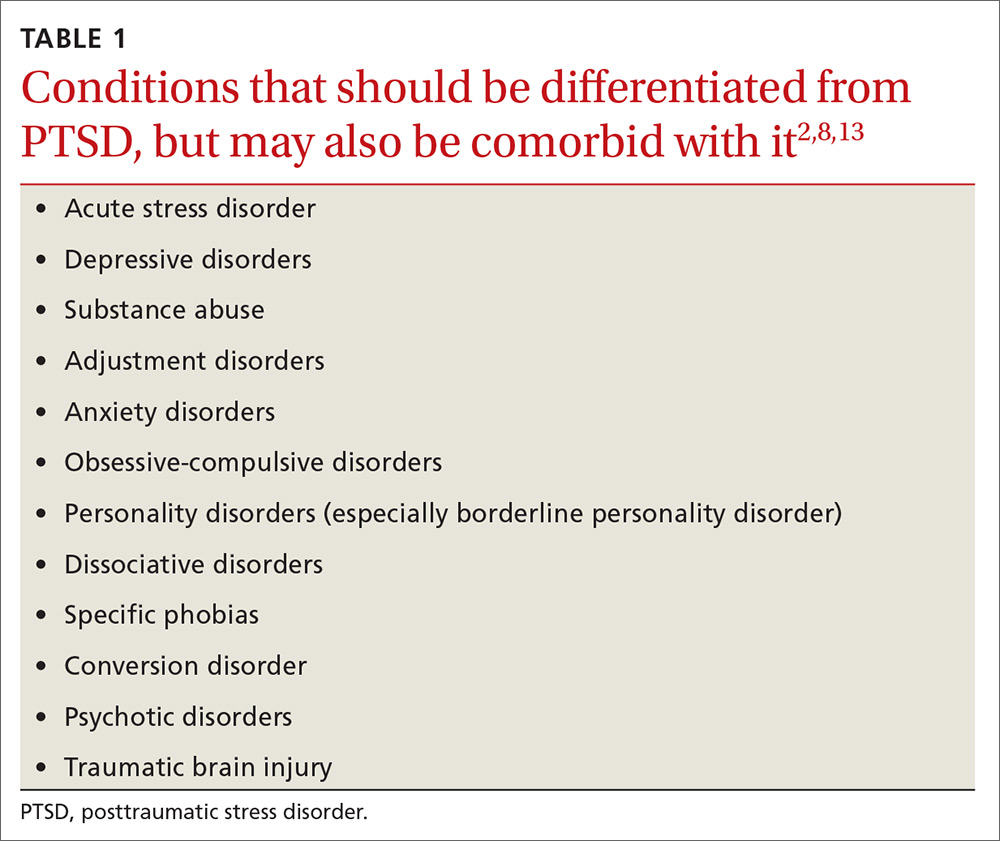

PTSD must be differentiated from other mental health conditions with overlapping symptoms (TABLE 12,8,13), but it may also be comorbid with one or more of these other conditions. When patients with PTSD do report mental health symptoms, providers often focus on the depressive symptoms that overlap with PTSD, and on substance use, which often accompanies PTSD, leaving PTSD undetected.9

Given that depressed/irritable mood, decreased participation in pleasurable activities, negative views of the world, attention difficulties, sleep difficulties, feelings of guilt, and agitation/restlessness are symptoms of both depression and PTSD,2 it is particularly important to screen patients with depressive symptoms for trauma history.

Why PTSD is often missed

Due to the impact of PTSD on overall health, the rates of PTSD in primary care clinics may be higher than in the general population.14 Thus, primary care clinicians are likely seeing PTSD more often than they realize. In fact, a systematic review showed that clinicians detected 0% to 52% of their patients with PTSD, missing at least half of all PTSD diagnoses.9

Detecting PTSD can be challenging for several reasons. Symptoms can span the emotional, social, physical, and behavioral aspects of an individual’s life, so patients and clinicians alike may regard symptoms as unrelated to PTSD.8 Primary symptom presentation may vary, with some people reporting anxiety symptoms, others mostly depressive symptoms, and others arousal, dissociative, or—as in our patient’s case—somatic symptoms.2 In affected children, parents may report emotional or behavioral problems without mentioning the trauma.2 Additionally, for traumas that were not a single event, such as long-term child abuse, patients may have difficulty identifying symptom onset.2