In 2009, the VA announced a goal of ending veteran homelessness by 2015.1 The primary focus of this new policy has been housing veterans experiencing chronic homelessness, many of whom languish outside the VA housing system. Since that time, progress has been made with point-in-time enumerations indicating that veteran homelessness has decreased nationally. Despite this progress, however, more than 55,000 veterans are still estimated to experience homelessness each night.2

Historically, the VA has offered an array of services specifically meant to alleviate veteran homelessness (grant, per diem, and other transitional housing programs; vocational rehabilitation, etc).3 The majority of these programs require some period of veteran abstinence as a condition for providing housing services. The recent move toward permanent “housing first” programs with few conditions for enrollment and participation provides new opportunities for housing veterans experiencing chronic homelessness, who are the specific target of the goal of ending veteran homelessness.4

Because veterans experiencing chronic homelessness have additional, substantial need for medical, psychiatric, and substance-abuse services, the VA also offers these services to this population.5-7 Veterans experiencing homelessness also may access parallel non-VA services.8 Information about veterans outside of traditional VA housing services, specifically those housed in low-demand shelters, is needed to develop services for this population and will be critical to success in ending veteran homelessness.

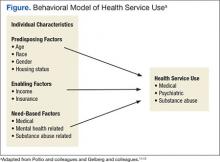

The Behavioral Model of Health Services Use9-11 and its later refinement, the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Persons,12 have been used to conceptualize health care service use (Figure). In these models, health service use is predicted by 3 types of factors: predisposing factors (eg, age, race, gender, residential history), enabling factors (eg, availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability), and service need factors (eg, substance-use disorders, mental health problems, physical health problems).

Studies applying these models of health care service use to both general homeless populations and, specifically to populations of veterans experiencing homelessness have found that service use is most influenced by need-based factors (eg, drug abuse, poor health, mental health problems).6,12-20 These same studies indicate that predisposing factors (eg, age, race, and gender) and enabling factors (eg, insurance, use of other services, and usual place of care) are also associated with service use, though less consistently.

Studies focused on veterans experiencing homelessness, however, included only treatment-seeking populations, which are not necessarily representative of the broader population of veterans experiencing homelessness. Additionally, none of these prior studies focused on the unique subset of veterans residing in low-demand shelters (characterized by unlimited duration of stay, no government ID or fee required for entry, and no requirement for service participation). This is a population that seems to be less engaged in services but nevertheless is challenged.21 This study, therefore, is focused on nontreatment seeking veterans residing in a low-demand shelter. The study applied the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use and the Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Persons to examine use of VA and non-VA services.

Study Parameters

This study was conducted in Fort Worth, Texas, the 17th largest city in the U.S. with more than 810,000 residents.22 In 2013, a biennial point-in-time count identified about 2,300 individuals who were homeless in Fort Worth. Most were found in emergency shelters (n = 1,126, 50%) or transitional housing (n = 965, 40%). Slightly more than 10% (n = 281) were found to be unsheltered: sleeping on the streets or in encampments, automobiles, or abandoned buildings.23 Although national estimates identify 12% of all adults who are homeless as veterans,2 only 8% (n = 189) of people experiencing homelessness in Fort Worth reported military service.23

Access to the full array of VA emergency department (ED), inpatient, and outpatient medical, psychiatric, and substance-abuse services are available to veterans experiencing homelessness at the Dallas VA Medical Center (DVAMC), located 35 miles away. Only VA outpatient medical, psychiatric, and substance-related services are available in Fort Worth through the VA Outpatient Clinic and Health Care for the Homeless Veterans (HCHV) program. If veterans experiencing homelessness seek care outside of the VA system, a comprehensive network of emergency, inpatient and outpatient medical, psychiatric, and substance-related services is available in Fort Worth.

Sample

The study sample included 110 adult male veterans randomly recruited as they awaited admission to a private, low-demand emergency shelter. The study excluded veterans with a dishonorable discharge to ensure participants were eligible for VA services. Institutional review board approvals were obtained prior to the study from the University of Texas at Arlington and DVAMC. All participants provided informed consent and were given a $5 gift for their involvement.