Trainees were educated about the use of the DT at time of diagnosis and across the disease trajectory. The 4-week CoE curriculum included 2 weeks of conference time to teach about the roles of psychologist, oncology social worker, and survivorship NP in assessing and initiating interventions to address the multidimensional components of the DT. Trainees working with a veteran who was distressed participated in the assessment(s) and intervention(s) for all components of distress that were endorsed.

Results

A total of 866 distress screenings were performed during the first 2 years of the project. Since all patients were screened at all visits, the 866 distress screenings reflect multiple screenings for 445 unique patients. Of the 866 screenings, 290 (33%) had distress scores of ≥ 4, meeting the criteria for intervention. Screenings reflected patient visits at any point in the disease trajectory. Because this was a new standard of care QI project rather than a research project, additional data, such as diagnosis or staging, were not collected, and IRB approval was not needed.

Because the NCCN Guideline recommendation for intervention is a score of ≥ 4, the descriptive statistics focused on those with moderate-to-severe distress. However, there were numerous occasions when the veteran would report a score of 0 to 3 and still endorse a number of the problems on the DT. The CNS and RN on the team discussed these findings with the appropriate discipline. For example, if the veteran reported a score of 1 but endorsed all 6 components on the emotional problem list, the nurses discussed the patient with the social worker or psychologist to determine whether behavioral health intervention was needed.

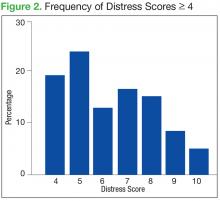

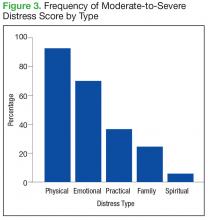

The mean distress score for the 290 screenings ≥ 4 was 6.3 on a 0 to 10 scale; median was 6.0 and mode 5.0. Two hundred ten of these screenings (72%) were categorized as moderate distress (4-7), and 80 patients (28%) reported severe distress (Figure 2). If the veteran left a box empty on the problem list, itwas recorded as missing. The frequency that patients reported each type of distress are reported in Figure 3.

The incidence of each component of distress, from those screenings with a score of ≥ 4 is described below, along with case study examples for each component. Team members involved in patient interventions provided these case studies to demonstrate clinical examples of the veteran’s distress from the problem list on the DT.

Practical/Family Distress

Practical issues were reported in 38% of the screenings (109/290). Intervention for moderate-to-severe distress associated with practical problems and family issues was provided by the team social worker. The social worker frequently addressed transportationrelated distress. Providing transportation was essential for adherence to clinic appointments, follow-up testing, treatments, and ultimately, disease management. Housing was also a problem for many veterans. It is critical that patients have access to electricity, heating, food, and water to be able to safely undergo adjuvant therapy. Thus, treatments decisions could be impacted by the veterans’ housing and transportation issues; immediate access to social work support is essential for quality cancer care.