Systemic sclerosis (SSc), also called scleroderma, is a rare but serious autoimmune connective tissue disease that has multiple fluctuating pathologic manifestations throughout its temporal course. Estimates have shown that the incidence is 10 to 20 cases per 1 million, and the prevalence is 4 to 253 cases per 1 million.1,2 Given the rarity of this incurable condition, it is vital that primary care providers (PCPs) are able to recognize its unique features early to limit and prevent acute and chronic complications. This case report discusses a patient’s journey with late-diagnosed scleroderma in order to convey these broad manifestations and what providers can do to manage it with their patients.

Case Presentation

Mr. P is a 60-year-old African American male with a history of hypertension, recurrent digital ulcers, pulmonary hypertension (PH), interstitial lung disease (ILD), kidney involvement, congestive heart failure (CHF), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Mr. P’s workup began in his late 40s with resistant hypertension, resistant GERD, and multiple hospitalizations for hypertensive urgency. It was not until he was 54 years old that he was diagnosed with mixed connective tissue disorder with sclerodermatous predominance.

Review of systems throughout his medical examinations in his 50s were notable for skin tightening over his hands and shoulders, skin hypopigmentation over his scalp and face, and hair loss. Mr. P was found to have Raynaud phenomenon beginning with his original presentation and digital ulceration without complications of gangrene or autoamputation. Aggregate physical examinations were notable for digital ulceration, skin tightening/sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. Serologic markers were notable for the following:

- Positive ANA (antinuclear antibody) with titer of 1:1,280/homogenous pattern;

- Positive anti-RNP (antiribonucleoprotein) with titer of 171.2;

- Positive anti-Scl-70 (antitopoisomerase I) with titer of 108.1;

- Positive anti-SM (anti-Smith antibody) with titer of 30.2;

- Positive anti-Ro (SSA) with titer of 107.6;

- Negative anti-La (SSB) with titer of 1.3;

- Negative anti-dsDNA (anti-double stranded DNA) with titer of 9; and

- Negative ACA (anticentromere antibody).

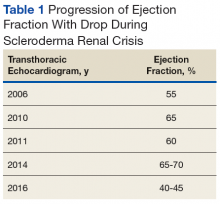

Early transthoracic echocardiograms revealed an ejection fraction (EF) initially at 55% with evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy. Following treatment with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE-5 inhibitors) and endothelin-1 antagonists for pulmonary hypertension, serial transthoracic echocardiograms showed improvement in his EF.

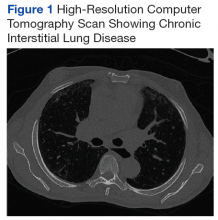

At age 60 years, Mr. P's EF dropped to 40% and he was hospitalized for hypertensive urgency (Table 1).A chest X-ray did not show signs of ILD, but a subsequent high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan was consistent with chronic ILD with a main pulmonary artery diameter of 3 cm (Figure 1).

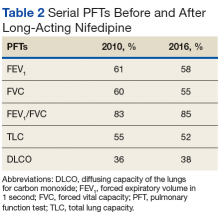

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) conducted in 2010 (Table 2) revealed a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) at 61% of normal and a forced vital capacity (FVC) at 60% of normal, with an FEV1/FVC ratio at a normal value of 83%. His total lung capacity (TLC) was 55% of normal with a diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) at 36% of normal. These findings confirmed restrictive lung disease, which was compatible with a diagnosis of chronic ILD. Mr. P was started on long-acting nifedipine, a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, to control blood pressure.Six years later, another PFT showed a FEV1 at 58%, FVC at 55%, FEV1/FVC ratio at 85%, TLC at 52%, and DLCO at 38% of normal (Table 2).In subsequent years, Mr. P was hospitalized several times, secondary to digit pain, ulcerations, and osteomyelitis. His first episode was 1 year after his scleroderma diagnosis, when he was hospitalized for 6 days for complications of SSc and finger pain. The following year, he had a 3-day hospitalization for hypertensive urgency and right third-digit osteomyelitis, treated initially with IV fluids, levofloxacin, and vancomycin, and then ceftaroline for 1 month. Throughout the next 6 years, Mr. P presented multiple times with fingertip ulcerations and was followed in the Infectious Disease clinic for recurrent osteomyelitis. He found some relief with systemic antibiotics, including augmentin, minocycline, moxifloxacin, and doxycycline.

At age 59, he was hospitalized for scleroderma renal crisis (SRC). Early in his disease, his kidney function was normal, but the SRC was discovered after an abrupt rise in his blood pressure (BP) and an increase in serum creatinine (SCr) from 1.2 mg/dL at baseline to 3.06 mg/dL. The presence of brown granular cast in his urine prompted a renal biopsy that showed thrombotic microangiopathy with schistocytes. Mr. P was started on captopril and remained stable with outpatient follow-up for this renal complication.