Statistical Analysis

IBM (Armonk, NY) Statistical Package for Social Sciences software was used to evaluate for differences in Fib-4, platelet count, prevalence of cirrhosis, prevalence of medical comorbidities, prevalence of mental health comorbidities, prevalence of the social issues defined in the Methods section, time from referral to time of appointment date, and SVR12 rate between the VA and Choice groups.

Exclusions

There were 15 veterans in the VA group who had a wait time of > 100 days. Of these, 5 (33%) were initially Choice referrals, but due to negative interactions with the Choice provider, the veterans returned to VALLHCS for care. Two of the 15 (13%) did not keep appointments and were lost to follow up. Six of the 15 (40%) had medical comorbidities that required more immediate attention, so HCV treatment initiation was deliberately moved back. The final 2 veterans scheduled their appointments unusually far apart, artificially increasing their wait time. Given that these were unique situations and some of the veterans received care from both Choice and VA providers, a decision was made to exclude these individuals from the study.

It has been shown that platelet count correlates with degree of liver fibrosis, a concept that is the basis for the Fib-4 scoring system.12 Studies have shown that platelet count is a survival predictor in those with cirrhosis, and thrombocytopenia is a negative predictor of HCV treatment success using peginterferon and ribavirin.13,14 Therefore, the VA memorandum automatically assigned the sickest individuals to the VA for HCV treatment. The goal of this study was to compare the impact of factors other than stage of fibrosis on HCV treatment success, which is why the 12 veterans with platelet count < 100,000 in the VA group were excluded. There were no veterans with platelet count < 100,000 in the Choice group.

When comparing SVR12 rates between the VA and Choice groups, every veteran treated at VALLHCS in FY 2016 was included, increasing the number in the VA group from 100 to 320 and therefore the power of this comparison.

Results

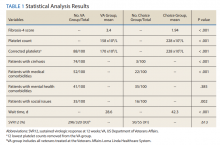

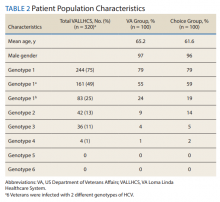

A summary of the statistical analysis can be found in Table 1. The genotype distribution was consistent with epidemiological studies, including those specific to veterans.15,16 There were statistically significant differences (P < .001) in mean Fib-4 and mean platelet count. The VA group had a higher Fib-4 and lower platelet count. Seventy-four percent of the VA population was defined as cirrhotic, while only 3% of the Choice population met similar criteria (P < .001). The VA and Choice groups were similar in terms of age, gender, and genotype distribution (Table 2).

The VA group was found to have a higher prevalence of comorbidities that affected HCV treatment. These conditions included but were not limited to: chronic kidney disease that precluded the use of certain medications, any condition that required medication with a known interaction with DAAs (ie, proton pump inhibitors, statins, and amiodarone), and cirrhosis if it impacted the treatment regimen. The difference in the prevalence of mental health comorbidities was not significant (P = .39), but there was a higher prevalence of social issues among the VA group (P = .002).

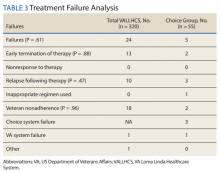

The mean wait time from referral to appointment was 28.6 days for the VA group and 42.3 days for the Choice group (P < .001), indicating that a Choice referral took longer to complete than a referral within the VA for HCV treatment. Thirty of the 71 (42%) veterans seen by a Choice provider accrued extraneous cost, with a mean additional cost of $8,561.40 per veteran. In the Choice group, 61 veterans completed a treatment regimen with the Choice HCP. Fifty-five veterans completed treatment and had available SVR12 data (6 were lost to follow up without SVR12 testing) and 50 (91%) had confirmed SVR12. The charts of the 5 treatment failures were reviewed to discern the cause for failure. Two cases involved early termination of therapy, 3 involved relapse and 2 failed to comply with medication instructions. There was 1 case of the Choice HCP not addressing simultaneous use of ledipasvir and a proton pump inhibitor, potentially causing an interaction, and 1 case where both the VA and Choice providers failed to recognize indicators of cirrhosis, which impacted the regimen used.

In the VALLHCS group, records of 320 veterans who completed treatment and had SVR12 testing were reviewed. While the Choice memorandum was active, veterans selected to be treated at VALLHCS had advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, medical and mental health comorbidities that increased the risk of treatment complications or were considered to have difficulty adhering to the medication regimen. For this group, 296 (93%) had confirmed SVR12. Eighteen of the 24 (75%) treatment failures were complicated by nonadherence, including all 13 cases of early termination. One patient died from complications of decompensated cirrhosis before completing treatment, and 1 did not receive HCV medications during a hospital admission due to poor coordination of care between the VA inpatient and outpatient pharmacy services, leading to multiple missed doses.

The difference in SVR12 rates (ie, treatment failure rates), between the VA and Choice groups was not statistically significant (P = .61). None of the specific reasons for treatment failure had a statistically significant difference between groups. A treatment failure analysis is shown in Table 3, and Table 4 indicates the breakdown of treatment regimens.