Bilateral lower extremity edema is a common condition with a broad differential diagnosis. New, severe peripheral edema implies a more nefarious underlying etiology than chronic venous insufficiency and should prompt a thorough evaluation for underlying conditions, such as congestive heart failure (CHF), cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, hypoalbuminemia, or lymphatic or venous obstruction. We present a case of a patient with sudden onset new bilateral lower extremity edema due to a rare adverse drug reaction (ADR) from valproate.

Case Presentation

A 63-year-old male with a history of seizures, bipolar disorder type I, and memory impairment due to traumatic brain injury (TBI) from a gunshot wound 24 years prior presented to the emergency department for witnessed seizure activity in the community. The patient had been incarcerated for the past 20 years, throughout which he had been taking the antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) phenytoin and divalproex and did not have any seizure activity. No records prior to his incarceration were available for review.

The patient recently had been released from prison and was nonadherent with his AEDs, leading to a witnessed seizure. This episode was described as preceded by an electric sensation, followed by rhythmic shaking of the right upper extremity without loss of consciousness. His regimen prior to admission included divalproex 1,000 mg daily and phenytoin 200 mg daily. His only other medication was folic acid.

Neurology was consulted on admission. An awake and asleep 4-hour electroencephalogram showed intermittent focal slowing of the right frontocentral region and frequent epileptiform discharges in the right prefrontal region during sleep, corresponding to areas of chronic right anterior frontal and temporal encephalomalacia seen on brain imaging. His seizures were thought likely to be secondary to prior head trauma. While the described seizure activity involving the right upper extremity was not consistent with the location of his prior TBI, neurology considered that he might have simple partial seizures with multiple foci or that his seizure event prior to admission was not accurately described. The neurology consult recommended switching from phenytoin 200 mg daily to lacosamide 100 mg twice daily on admission. His prior dose of divalproex 1,000 mg daily also was resumed for its antiepileptic effect and the added benefit of mood stabilization, as the patient reported elevated mood and decreased need for sleep on admission.

Eight days after changing his AED regimen, the patient was found to have new onset bilateral grade 1+ pitting edema to the level of his shins. He had no history of dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, dysuria, or changes in his urination. Although medical records from his incarceration were not available for review, the patient reported that he had never had peripheral edema.

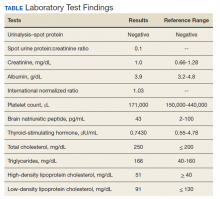

On physical examination, the patient had no periorbital edema, jugular venous pressure of 8 cm H2O, negative hepatojugular reflex, unremarkable cardiac and lung examination, and grade 2+ posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses bilaterally. He underwent extensive laboratory evaluation for potential underlying causes, including nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, hypothyroidism, and CHF (Table). Valproate levels were initially subtherapeutic on admission (< 10 µg/mL, reference range 50-125 µg/mL) then rose to within therapeutic range (54 µg/mL-80 µg/mL throughout admission) after neurology recommended increasing the dose from 1,000 mg daily to 1,500 mg daily. His measured valproate levels were never supratherapeutic.

An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm unchanged from admission. Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular (LV) size and estimated LV ejection fraction of 55 to 60%. Abdominal ultrasound showed no evidence of cirrhosis and normal portal vein flow. Ultrasound of the lower extremities showed no deep venous thrombosis or valvular insufficiency. The patient was prescribed compression stockings. However, due to memory impairment, he was relatively nonadherent, and his lower extremity edema worsened to grade 3+ over several days. Due to the progressive swelling with no identified cause, a computed tomographic venogram of the abdomen and pelvis was performed to determine whether an inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombus was present. This study was unremarkable and did not show any external IVC compression.

After extensive evaluation did not reveal any other cause, the temporal course of events suggested an association between the patient’s peripheral edema and resumption of divalproex. His swelling remained stable. Discontinuation of divalproex was considered, but the patient’s mood remained euthymic, and he had no further seizure activity while on this medication, so the benefit of continuation was felt to outweigh any risks of switching to another agent.