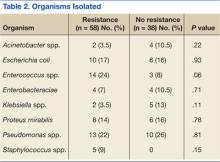

No significant differences in the types of organisms isolated were noted between the groups (Table 2). The most common pathogens isolated were Pseudomonas aeruginosa (24%), Enterococcus spp. (18%), Escherichia coli (17%), Proteus spp. (14%), Klebsiella spp. (7%), and Acinetobacter spp. (6%).

Thirty-six percent of the pathogens in the first cultures were not treated with any antibiotics, because they were considered as colonizers or contaminants. Only 61% of pathogens in the no resistance group vs 78% in the resistance group were exposed to antimicrobial treatment. In those veterans who were treated, antibiotic usage on the first urine culture was assessed to determine whether any relationship existed between receipt of a particular antimicrobial class and development of resistance. Fluoroquinolones were the most commonly prescribed antimicrobials in both the resistance and no resistance groups (Table 3).

Four risk factors (ASIA grade, antibiotic treatment duration, prior use of a cephalosporin, and prior use of penicillin) were initially identified by logistic regression analyses as being associated with resistance development. Since veterans in the resistance group were significantly older than those in the no resistance group, the analysis was repeated with age as a covariate to independently assess the association between the risk factors and resistance. After controlling for age, no significant association between the ASIA grade and resistance was identified (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.03; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.66 – 1.6). Median duration of antibiotic treatment was 6 days in all patients, 3.5 days in the no resistance group, and 9 days in the resistance group. Longer duration of treatment significantly predicted resistance (adjusted OR, 1.07; P = .03; 95% CI: 1.01 – 1.03). For every additional day the patient was on an antibiotic, he or she was 7% more likely to develop resistance.

The incidence of resistant organisms after exposure to a cephalosporin was not statistically different between groups (adjusted OR, 1.74; P = .36; 95% CI: 1.0 – 1.2). In the resistance group, 28% of the antibiotics prescribed were cephalosporins (cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, and cefepime), which were used for Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In the no resistance group, 17% of the antibiotics prescribed were cephalosporins (cefepime only) and were used for Proteus mirabilis.

Organisms treated with penicillin were significantly less likely to become resistant (adjusted OR, 0.26; P = .04; 95% CI: 0.07 - 0.96). In the resistance group, 16% of the antibiotics were penicillins (piperacillin/tazobactam), which were used for Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. In the no resistance group, 22% of the antibiotics were penicillins (amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate and piperacillin/tazobactam), which were used for Proteus mirabilis, Enterococcus faecalis, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Discussion

Longer duration of treatment significantly increased resistance on the subsequent culture in this study. For every additional day the patient was on an antibiotic, he or she was 7% more likely to develop a resistance. However, the potential impact of using a given antibiotic class on the acquisition of resistance in patients with SCI who had a UTI was not demonstrated. Surprisingly, the use of a cephalosporin was not associated with an increased incidence of resistance in this study, which was inconsistent with the findings from other studies.10 Weber and colleagues evaluated nosocomial infections in the intensive care unit. The authors suggested that restriction on the use of third-generation cephalosporins might decrease antibiotic resistance, especially in extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing gram-negative bacilli.11

The difference in this study may be explained by the lower incidence of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, which are known to exhibit inducible resistance on exposure to third-generation cephalosporins. Conversely, it was found that patients treated with a penicillin were significantly less likely to develop resistant organisms from subsequent cultures. The most common penicillin used in this study’s patient population was piperacillin/tazobactam.

For complicated UTIs including pyelonephritis, the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines for the management of urinary and male genital tract infections recommend treatment for 3 to 5 days after defervescence or control of complicating factors.12 These recommendations could lead to much shorter treatment durations than the traditional 14-day “standard” course often prescribed. One meta-analysis recommends a 5-day course for UTIs without fever in patients with SCI vs a 14-day course for patients with fever.13 Due to the lack of data, care often varies based on the patient’s clinical status, provider experience, and opinions. The Pannek study surveyed 16 centers that specialized in SCI care. When compared with the recommendations in the EAU guidelines, the study found providers in > 50% of the responding facilities overtreated UTIs.14