New Diffuse Glioma Classification

Since the issuance of the previous edition of the WHO classification of CNS tumors in 2007, several sentinel discoveries have been made that have advanced our understanding of the underlying biology of primary CNS neoplasms. Since a detailed review of these findings is beyond the scope and purpose of this manuscript and salient reviews on the topic can be found elsewhere, we will focus on the molecular findings that have been incorporated into the recently revised WHO classification.10 The importance of providing such information for proper patient management is illustrated by the recent acknowledgement by the American Academy of Neurology that molecular testing of brain tumors is a specific area in which there is a need for quality improvement.11 Therefore, it is critical that these underlying molecular abnormalities are identified to allow for proper classification and treatment of diffuse gliomas in the veteran population.

As noted previously, based on VA cancer registry data, diffuse gliomas are the most commonly encountered primary CNS cancers in the veteran population. Several of the aforementioned seminal discoveries have been incorporated into the updated classification of diffuse gliomas. While the recently updated WHO classification allows for the assignment of “not otherwise specified (NOS)” diagnostic designation, this category must be limited to cases where there is insufficient data to allow for a more precise classification due to sample limitations and not simply due to a failure of VA pathology laboratories to pursue the appropriate diagnostic testing.

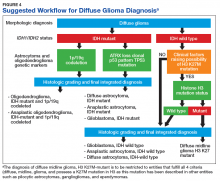

Figure 4 presents the recommended diagnostic workflow for the workup of diffuse gliomas. As illustrated in the above cases, a variety of different methodologies, including immunohistochemical, FISH, loss of heterozygosity analysis, traditional and NGS may be applied when elucidating the status of molecular events at critical diagnostic branch points.

Each of these methods has their individual strengths and weaknesses. In addition, tests like assessment of mutations within selected histone genes probably are applied best to cases where such entities commonly occur (ie, midline tumors) and not in every case. Similarly, although in the cases presented above several different redundant methodologies were employed to answer questions critical in the proper classification of diffuse gliomas (eg, immunohistochemical, pyrosequencing, and NGS analysis of IDH1 mutational status), these were presented for illustrative purposes only. Once a given test identifies the genetic changes that allow for proper classification of diffuse gliomas, additional confirmatory testing is not mandatory. Although not recommended, due to the rarity of non-R132H IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in GBM occurring in the elderly, immunohistochemistry for R132H mutant IDH1 may be considered sufficient for initial determination of IDH mutational status in this patient population (eg, appropriate histology for the diagnosis of GBM in an elderly patient). However, caution must be exercised in cases where other entities lower grade lesions, such as pilocytic astrocytoma, pleomorphic astrocytoma, and ganglioglioma, enter the histologic differential diagnosis. In such scenarios, additional sequencing of IDH1 and IDH2 genes, as well as sequencing of other potentially diagnostically relevant alterations (eg, BRAF) may be reasonable. This decision may be aided by a web-based application for calculating the probability of an IDH1/2 mutation in a patient’s diffuse glioma (www.kcr.uky.edu/webapps/IDH/app.html).12 Finally, once the diagnosis of a high-grade diffuse glioma has been reached, assessment of the methylation status of the MGMT promoter should be performed, particularly in elderly patients with GBM, to provide important predictive and prognostic information.6,13,14