Outcome

The patient was treated with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) delivered simultaneously to both the prostate and high-risk retroperitoneal margins of the DDLPS, as well as concurrent androgen deprivation therapy. Five months after completed radiotherapy, resection of the DDLPS was attempted. However, palliative tumor debulking was instead performed due to extensive locoregional invasion with involvement of the posterior peritoneum and ipsilateral quadratus, iliopsoas, and psoas muscles, as well as the adjacent lumbar nerve roots.

At present, the patient is undergoing surveillance imaging every 3 months to reevaluate his underlying disease burden, which has thus far been radiographically stable. Current management at the primary care level is focused on preserving quality of life, particularly maintaining mobility and functional independence.

Discussion

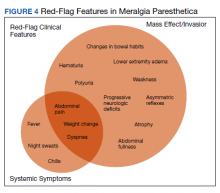

Although generally a benign entrapment neuropathy, MP bears well-established associations with multiple forms of must-not-miss pathology. Here, we present the case of a veteran in whom MP was the index presentation of a massive retroperitoneal liposarcoma, stressing the importance of a thorough history and physical examination in all patients presenting with MP. The case presented herein highlights many of the red-flag signs and symptoms that primary care physicians might encounter in patients with retroperitoneal pathology, including MP and MP-like syndromes (Figure 4).

In this case, the pretest probability of a spontaneous and uncomplicated MP was high given the patient’s sex, age, body habitus, and DM; however, there important atypia that emerged as the case evolved, including: (1) the progressive course; (2) proximal right lower extremity weakness; (3) asymmetric patellar reflexes; and (4) numerous clinical stigmata of intraabdominal mass effect. The patient exhibited abnormalities on abdominal examination that suggested the presence of an underlying intraabdominal mass, providing key diagnostic insight into this case. Given the slowly progressive nature of liposarcomas, we feel the abnormalities appreciated on abdominal examination were likely apparent during the initial presentation.18

There are numerous cognitive biases that may explain why an abdominal examination was not prioritized during the initial presentation. Namely, the patient’s numerous risk factors for spontaneous MP, as detailed above, may have contributed to framing bias that limited consideration of alternative diagnoses. In addition, the patient’s physical examination likely contributed to search satisfaction, whereby alternative diagnoses were not further entertained after discovery of findings consistent with spontaneous MP.19 Finally, it remains conceivable that an abdominal examination was not prioritized as it is often perceived as being distinct from, rather than an integral part of, the neurologic examination.20 Given that numerous neurologic disorders may present with abdominal pathology, we feel a thorough abdominal examination should be considered part of the full neurologic examination, especially in cases presenting with focal neurologic findings involving the lower extremities.21

Collectively, this case alludes to the importance of close clinical follow-up, as well as adequate anticipatory patient guidance in cases of suspected MP. In most patients, the clinical course of spontaneous MP is benign and favorable, with up to 85% of patients experiencing resolution within 4 to 6 months of the initial presentation.22 Common conservative measures include weight loss, garment optimization, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed for analgesia. In refractory cases, procedural interventions such as with neurolysis or resection of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, may be required after the ruling out of alternative diagnoses.23,24

Importantly, in even prolonged and resistant cases of MP, patient discomfort remains localized to the territory of the LFCN. Additional lower motor neuron signs, such as an expanding territory of sensory involvement, muscle weakness, or diminished reflexes, should prompt additional testing for alternative diagnoses. In addition, clinical findings concerning for intraabdominal mass effect, many of which were observed in this case, should lead to further evaluation and expeditious cross-sectional imaging. Although this patient’s early satiety, polyuria, bilateral lower extremity edema, weight gain, and lumbar plexopathy each may be explained by direct compression, invasion, or displacement, his report of progressive exertional dyspnea merits further discussion.

Exertional dyspnea is an uncommon complication of soft tissue sarcoma, reported almost exclusively in cases with cardiac, mediastinal, or other thoracic involvement.25-28 In this case, there was no evidence of thoracic involvement, either through direct extension or metastasis. Instead, the patient’s exertional dyspnea may have been attributable to increased intraabdominal pressure leading to compromised diaphragm excursion and reduced pulmonary reserve. In addition, the radiographic findings also raise the possibility of a potential contribution from preload failure due to IVC compression. Overall, dyspnea is a concerning feature that may suggest advanced disease.

Despite the value of a thorough history and physical examination in patients with MP, major clinical guidelines from neurologic, neurosurgical, and orthopedic organizations do not formally address MP evaluation and management. Further, proposed clinical practice algorithms are inconsistent in their recommendations regarding the identification of red-flag features and ruling out of alternative diagnoses.22,29,30 To supplement the abdominal examination, it would be reasonable to perform a pelvic compression test (PCT) in patients presenting with suspected MP. The PCT is a highly sensitive and specific provocative maneuver shown to enable reliable differentiation between MP and lumbar radiculopathy, and is performed by placing downward force on the anterior superior iliac spine of the affected extremity for 45 seconds with the patient in the lateral recumbent position.31 As this maneuver is intended to force relaxation of the inguinal ligament, thereby relieving pressure on the LFCN, improvement in the patient’s symptoms with the PCT is consistent with MP.

Conclusions

Spontaneous MP is a generally benign condition secondary to LFCN entrapment at the level of the inguinal ligament and is encountered frequently in the context of comorbid obesity and DM. However, MP bears known associations with high-risk pathologies that engender specific diagnostic and therapeutic considerations, including retroperitoneal mass lesions. The case presented herein highlights the utility of: (1) a focused history and review of systems to aid in the identification of red-flag symptoms and signs that might suggest a secondary etiology; and (2) a thorough abdominal examination in all patients who present with MP, especially in atypical presentations, cases with additional focal neurologic findings, or in patients who report progressive symptoms. Given the progressively aging population within the United States, coupled with an expanding prevalence of obesity and diabetes mellitus, recognition of the typical and atypical features of MP may be of progressive importance.