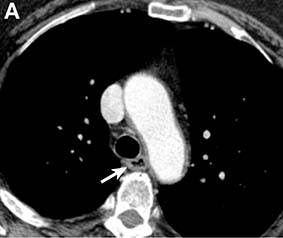

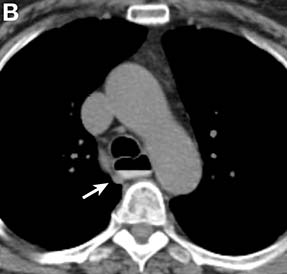

Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page X: Pseudoachalasia in paraneoplastic syndrome, with radiographic documentation of onset and evolution

A barium esophagogram revealed an esophagus with characteristic features of achalasia: dilatation, retention of air and fluid, and a “bird’s beak” configuration distally (Figure E). Botulinum injection into the distal esophagus provided the patient with partial relief of her swallowing symptoms.

Evidence supporting the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia associated with paraneoplastic syndrome in this patient is 1) the development of characteristic features of achalasia in association with SCLC, the cancer that is most often associated with paraneoplastic achalasia;1 2) a serum antibody characteristic of SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndrome; 3) peripheral neuropathy attributed to paraneoplastic syndrome; and 4) absence of an obstructive neoplasm at the gastroesophageal junction.

Pseudoachalasia associated with malignancy may occur by one of three mechanisms1-3: 1) Primary or secondary carcinoma located at or near the gastroesophageal junction, 2) neural invasion of the esophagus, or 3) as a component of the paraneoplastic syndrome. Pseudoachalasia associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome is rare (an estimated 1 in 750,000), although it may be becoming more common.1 The relatively rapid onset of dysphagia is a reported feature of pseudoachalasia, in contrast with the more gradual onset in primary achalasia. Our report documents radiographically the progression within a few months from a normal-diameter esophagus to a very dilated, poorly functioning esophagus. We know of no similar report. Botulinum toxin injection has been reported effective in a few cases.1

References

1. Katzka, D.A., Farrugia, G., Arora, A.S., et al. Achalasia secondary to neoplasia: a disease with a changing differential diagnosis. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:331-6.

2. Liu, W., Fackler, W., Rice, T.W., et al. The pathogenesis of pseudoachalasia (A clinicopathological study of 13 cases of a rare entity). Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:784-8.

3. Gockel, J., Eckardt, V.F., Scmitt, T., et al. Pseudoachalasia: a case series and analysis of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:378-85.