Answer to “What’s your diagnosis?” on page 2: Arteriovenous fistulas arising from the subclavian and coronary arteries

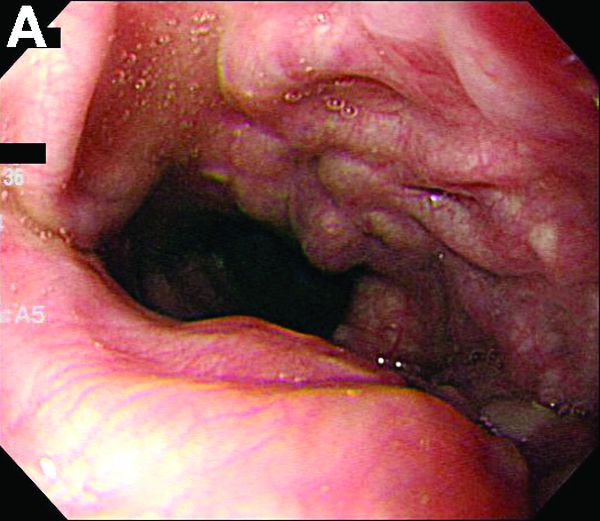

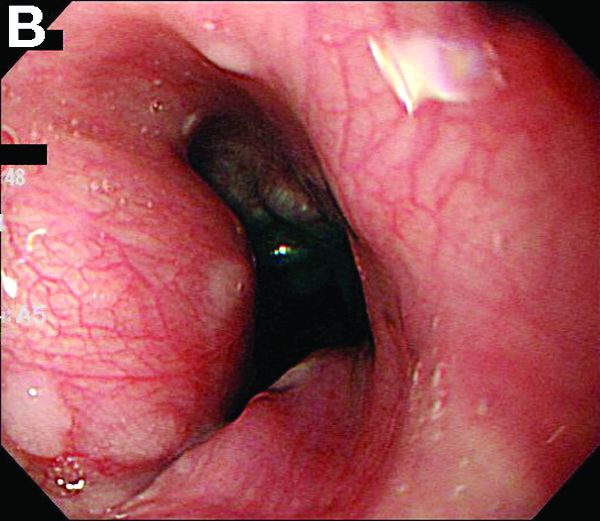

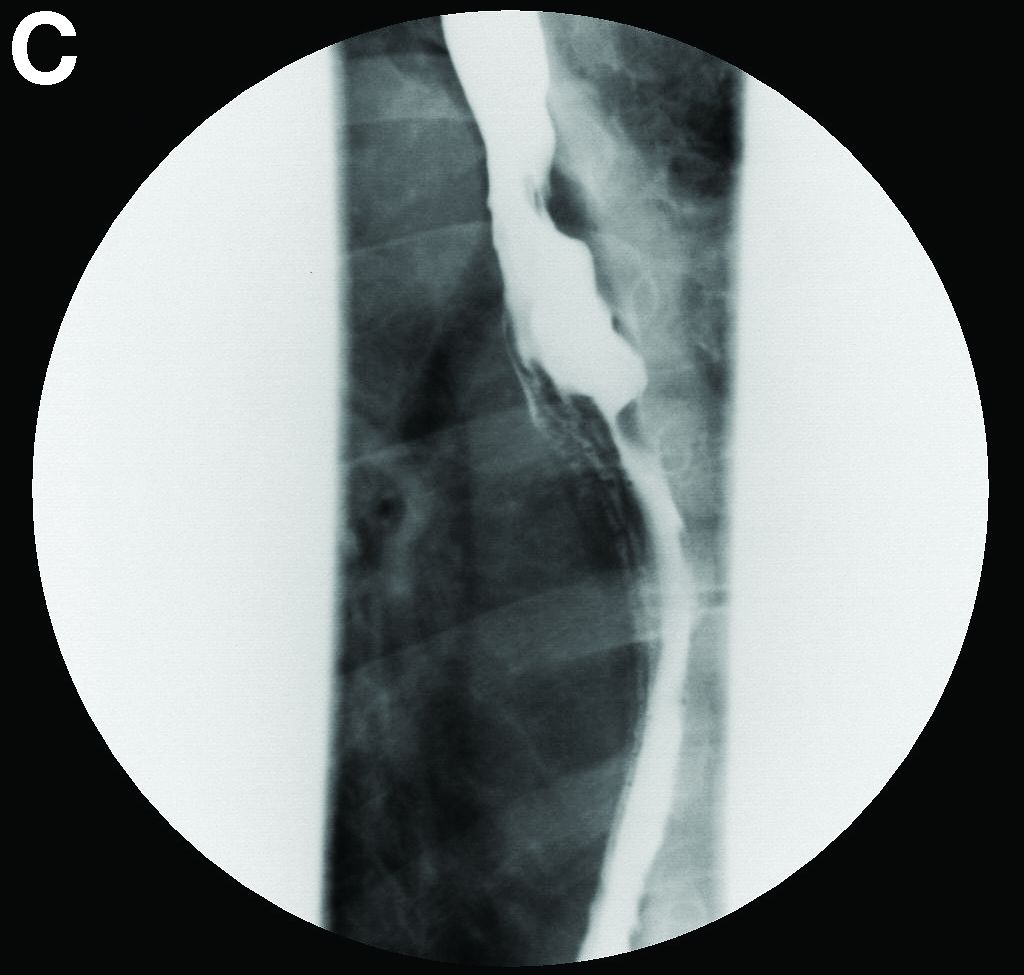

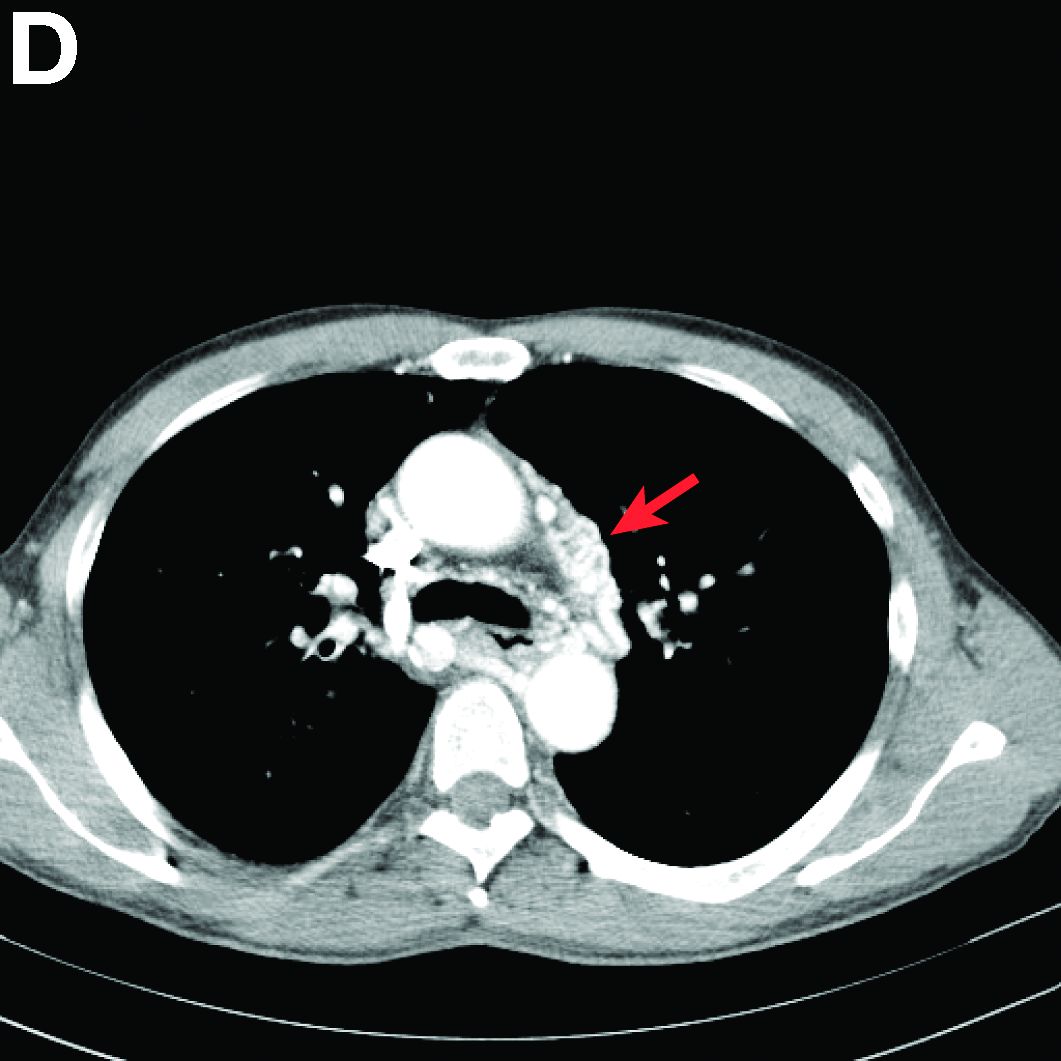

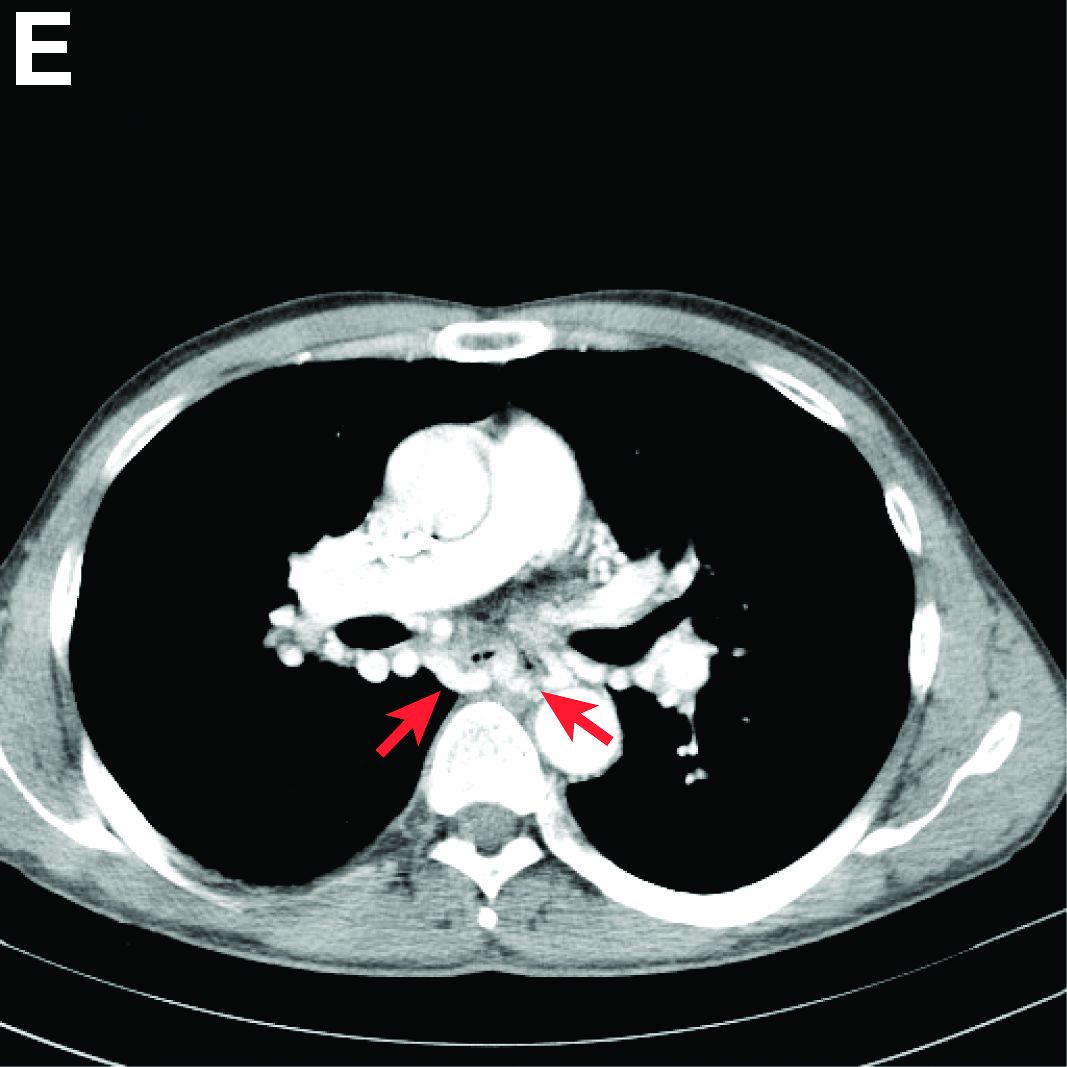

We performed aortography along with coronary angiography to find the feeding vessels for the vascular bundle (). There was an arteriovenous fistula that arose from the left subclavian artery, ran over the left mediastinum with the complex plexus, and emptied into the venous system of the left thorax. Multiple coronary artery fistulas originated in the left coronary artery, traversed the left and right mediastinum, and eventually emptied into the venous system of the mediastinum. The left anterior oblique view revealed a coronary artery fistula that arose from the distal right coronary artery and drained into the venous system of the thorax. In transthoracic echocardiography, the sizes of the left atrium and left ventricle were mildly dilated, but left ventricular systolic functions were preserved with an ejection fraction of 61%. We recommended surgery to the patient, but he refused invasive treatment. He will be followed with close observation.

A coronary artery fistula is usually of congenital origin, and connects a major coronary artery directly with the cardiac chamber, coronary sinus, superior vena cava, or pulmonary artery. However, its connection with a systemic venous system is extremely rare. Congenital subclavian arteriovenous fistulas are rare because they usually occur as a complication of previous trauma, percutaneous catheterization, or surgery.1 Complications include “steal” from the adjacent myocardium causing myocardial ischemia, thrombosis/embolism, cardiac failure, atrial fibrillation, rupture, endocarditis/endarteritis, and arrhythmia.2 Treatment options include close medical observation, surgical ligation, and catheter embolization.3

References

1. Brountzos, E.N., Kelekis, N.L., Danassi-Afentaki, D. et al. Congenital subclavian artery-to-subclavian vein fistula in an adult: treatment with transcatheter embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:675-7.

2. Wilde, P., Watt, I. Congenital coronary artery fistulae: six new cases with a collective review. Clin Radiol. 1980;31:301-11.

3. Mangukia, C.V. Coronary artery fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:2084-92.