SAN FRANCISCO – As the availability of more sensitive diagnostic methods such as reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction testing become more widespread, noroviruses are increasingly being recognized as important enteric pathogens in diverse populations.

"In the past, much of our knowledge about noroviruses has been hindered because we don’t have a good animal model or method for culturing norovirus," Dr. Hoonmo L. Koo said at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. "The majority of our current understanding has come from studying human outbreaks, volunteer challenge studies, and evaluating surrogate caliciviruses such as feline and murine caliciviruses, which don’t cause human infection but can be cultured."

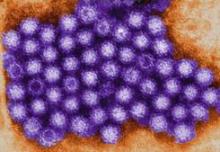

Noroviruses (NoVs) are classified into five genetic groups based on their RNA capsid sequences, with genogroup I (GI) and genogroup II (GII) NoVs causing the most human NoV infections. GII.4 NoV strains are the predominant circulating genotype in the United States and worldwide, said Dr. Koo of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. As reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction testing (RT-PCR) has become more available in recent years, NoVs "are now recognized as the most definable common cause of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis worldwide," he said. "They account for approximately half of all food-borne illness in the United States.

"Each year, NoVs cause about 21 million cases of infection in the United States. They occur throughout the year, but they peak in the winter season."

NoV outbreaks are common in children, travelers, restaurant patrons, military personnel, patients, and health care staff at hospitals, nursing homes, and other medical facilities. Dr. Koo and his associates conducted an 8.5-year surveillance study at Texas Children’s Hospital (TCH) investigating NoV, rotavirus (RV), and adenovirus prevalence at the facility before and after introduction of the RV vaccine in 2006. The study evaluated 8,173 stool samples from inpatients and outpatients at TCH from February 2002 to June 2010. The samples were evaluated for RV by antigen detection or electron microscopy and adenoviruses by electron microscopy. In addition, a subset of 3,222 stools were evaluated for NoV by RT-PCR (J. Ped. Infect. Dis. 2012 Aug. 3 [doi:10.1093/jpids/pis070]).

"We found that RV prevalence decreased significantly after the introduction of the RV vaccine in 2006," Dr. Koo said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology. "In more recent years, it decreased from about 9% in 2007 to 3% in 2010." At the same time, he continued, "NoV prevalence increased in 2004 and was consistently between 11% and 17% from 2004 to 2010. There was no significant increase in NoV prevalence after the RV vaccine was introduced in 2006."

The researchers concluded that NoVs have emerged as the most common viral gastroenteritis pathogen at TCH, which is one of the largest pediatric hospitals in the United States. "We believe that as RV prevalence continues to decline with vaccination, NoVs will soon eclipse rotaviruses as the most important cause of pediatric gastroenteritis in the United States and other countries where the RV vaccine is successfully administered," Dr. Koo said.

In a separate study, he and his associates evaluated stools from 571 international travelers who acquired diarrhea in Guatemala, India, and Mexico (J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:1673-6). NoVs were identified in 10% of cases of travelers’ diarrhea, and overall were the second most common pathogen following diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. "We concluded that NoVs are important pathogens of travelers’ diarrhea in multiple developing regions of the world," Dr. Koo said. "However, there was significant variation evident in the prevalence of NoV diarrhea and in the predominant genogroup infecting the travelers, depending on the specific geographic location and time period we looked at."

Immunocompromised patients also have been affected by NoVs. One report described 12 hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients with NoV gastroenteritis who were hospitalized for a median of 73 days (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1069-71). Half of the patients required supplemental feeding with enteral or parenteral nutrition, and two patients died: one secondary to malnutrition and chronic NoV gastroenteritis. "Future areas of NoV study include further defining the burden of disease in pediatric and immunocompromised populations," Dr. Koo said. "We need development of sensitive diagnostic assays that can be used by clinical laboratories. Unfortunately, the ELISA assay that we have now for NoV detection is relatively insensitive, and most clinical laboratories cannot perform RT-PCR. We need effective therapeutic agents to be developed, and we need an effective NoV vaccine."

Results from a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of an investigational NoV vaccine found a significantly lower frequency of viral gastroenteritis among vaccine recipients, compared with placebo recipients (37% vs. 69%, respectively; P = .006). It was found to be safe and well tolerated, and no severe adverse events were reported (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:2178-87). "The vaccine was also found to be immunogenic, with 70% of vaccine recipients producing a fourfold rise in serum total antibody and serum IgA," Dr. Koo said. "However, there are significant challenges to the development of NoV vaccines. In the NEJM study, the frequency and magnitude of serum antibody response with the vaccine was lower than what’s been observed with natural infection. Previous studies have shown that acquired immunity with natural infection may be short-lived: less than 2 years. So how long will the vaccine protection last?"