Discussion

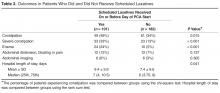

Patients initiated on opioid therapy were not prescribed prophylactic laxatives in 64% of our cohort in the inpatient setting. When prescribed, current laxative strategies did not effectively prevent constipation with 49% experiencing OIC. Our data serves as a strong reminder of the magnitude of the problem of OIC in the inpatient setting.

The strength of our paper lies in its role as a magnitude assessment. This retrospective review reveals for that among a diverse group of patients hospitalized within a large academic institution, OIC remains prevalent. Furthermore, the high incidence of severe constipation indicates the potential for increased health care costs and patient discomfort secondary to OIC emphasizing the importance of prevention of OIC. Recent guidelines have made a push toward prophylactic laxative utilization earlier. Specifically, the European Palliative Research Collaborative offers a “strong recommendation to routinely prescribe laxatives for the management or prophylaxis of opioid-induced constipation” [10]. Additionally, the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians suggests that “a physician should consider the initiation of a bowel regimen even before the development of constipation and definitely after the development of constipation” [11]. Our manuscript serves as a reminder that OIC remains a very prevalent problem and that prophylactic laxatives are still being underutilized.

This is a retrospective study and thus has inherent limitations. Specifically, we are limited to those cases of constipation that were documented in the medical record. The presentation of constipation is varied between patients. This variation in presentation of OIC is inherent to the disease process as is demonstrated in the broad definition for OIC [1]. The cases of constipation that we are reporting clearly were bothersome enough to warrant documentation in the medical record, and while there may have been cases that escaped documentation, we can be confident that the cases of OIC we are reporting are true cases of OIC. The numbers we report can therefore be taken to represent a minimum number of cases of constipation occurring in our study population.

It has been suggested that OIC prevalence varies with type of opioid and duration of opioid therapy [24]. We did not compare dose, type, or duration of opioid therapy in this study. This could certainly account for the seemingly higher rate of constipation within the group treated with prophylactic laxatives as compared with those not treated with prophylactic laxatives. Physicians likely have a higher propensity to prescribe prophylactic laxatives to patients receiving high doses of opioids who are in turn at higher risk for OIC. We cannot say whether differences in efficacy exist between prophylactic laxative regimens or which opioids (dose and duration) cause the most constipation based upon our data. Future studies incorporating dose, duration, and opioid type along with the variables we collected in this study could potentially construct successful logistic regression models with predictive power to identify those at highest risk of OIC.