Methods

Ethical Issues

This work met criteria for operational improvement activities and as such was exempt from ethics review. The team engaged patients who had undergone spinal surgery to serve as representatives to ensure that the improvements studied were important to them.

Setting and Patients

Our institution is a District General Hospital that serves a population of over 340,000 and has 3 consultant spinal surgeons. They work with 5 anesthesiologists on a regular basis and the patients are cared for by 3 clinical nurse practitioners. The patients are cared for on an elective orthopedic ward with nursing staff, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists who work regularly with spinal surgery patients. The mean age of our spinal surgery patients is 55 years and 55% are female. By age-group, 6.6% are aged 1–16 years, 50.8% aged 17–65 years, and 42.6% over 65 years. We define elective spinal surgery as non-emergency surgery, including discectomy, decompression, fusion and realignment operations to the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine.

Developing the Pathway

To develop the new pathway, input from the expert team of anesthesiologists and surgeons, other clinicians and staff, as well as patients were sought. Four patients were approached prior to surgery and asked for their thoughts on the existing clinical pathway. They were then shadowed during their journey by clinical staff to see where improvements to their clinical care could be made.

In addition to gathering input from staff and patients, we reviewed the literature for the best available evidence. We found a Cochrane review of 27 trials involving 1976 surgical patients that concluded that preoperative carbohydrate drinks reduced length of stay [6]. Similarly, although laxatives have not been shown to improve length of stay [7], it is known that constipation is exacerbated by opioid analgesia and causes distress [8].

Finally, we examined the ERPs for patients undergoing hip and knee replacement that already existed in our institution. We found they used standardized anesthetic regimens as well as “patient passports,” leaflets given to give patients telling them what to expect during and following joint replacement surgery. They were also implementing methods to help patients set daily aims on the ward.

A driver diagram was used to visualize the components of the process and the changes required to reach the intended aim of reduced length of stay and improved patient experience. We arrived at a list of 21 change ideas for modifying the standing pathway ( Table 1 ). All interventions were then tested using PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) cycles. After each PDSA cycle we reviewed how well the plan had gone and implemented suggestions for improvement in the next test cycle.PDSA Cycles

We began PDSA testing in November 2013. Below we describe selected pathway changes that we expected to be challenging because they involved many staff from different groups. Interventions that involved fewer people or a smaller group (eg, a change in anesthetic regimen or surgical technique) were easier to implement.

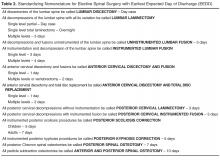

Standardizing Nomenclature

The spinal consultants agreed to 12 descriptions of elective spinal surgery to improve communication between team members ( Table 2 ). They were able to reduce the number of procedure descriptions from 135 to just 12. Theatre staff could determine from the procedure descriptions which equipment was required for the operation and ensure it was available at the time needed. Anesthetic staff felt better able to prepare for their operating lists with a prescription for preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative analgesia.