From the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health (Dr. Janevic) and the Medical School (Dr. Sanders), University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: Asthma prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are all greater among adult women compared to men. Appropriate asthma self-management can improve asthma control. We reviewed published literature about sex- and gender-related factors that influence asthma self-management among women, as well as evidence-based interventions to promote effective asthma self-management in this population.

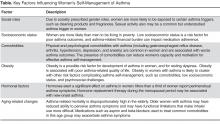

- Design: Based on evidence from the published literature, factors influencing women’s asthma self-management were categorized as follows: social roles and socioeconomic status, comorbidities, obesity, hormonal factors, and aging-related changes.

- Results: A number of factors were identified that affect women’s asthma self-management. These include: exposure to asthma triggers associated with gender roles, such as cleaning products; financial barriers to asthma management; comorbidities that divert attention or otherwise interfere with asthma management; a link between obesity and poor asthma outcomes; the effects of hormonal shifts associated with menstrual cycles and menopause on asthma control; and aging-associated barriers to effective self-management such as functional limitations and caregiving. Certain groups, such as African-American women, are at higher risk for poor asthma outcomes linked to many of the above factors. At least 1 health coaching intervention designed for women with asthma has been shown in a randomized trial to reduce symptoms and health care use.

- Conclusion: Future research on women and asthma self-management should include a focus on the relationship between hormonal changes and asthma symptoms. Interventions are also needed that address the separate and interacting effects of risk factors for poor asthma control that tend to cluster in women, such as obesity, depression, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

In childhood, asthma is more prevalent in boys than in girls. In adolescence and adulthood, however, asthma becomes a predominantly female disease, with hormonal factors likely playing a role in this shift [1,2]. Fu et al [3] reviewed daily asthma symptom diaries of 418 children. From age 5 to 7, boys had more severe symptoms, but by age 10 girls’ symptoms were becoming more severe. By age 14, the girls’ symptoms continued increasing while the boys’ symptoms began to decline. A meta-analysis by Lieberoth et al [4] found a 37% increased risk of post-menarchal asthma in girls with onset of menarche < 12 years. Together, these studies implicate female sex hormones in both the increased incidence and severity of asthma after puberty. In 2012, nearly 10% of adult women reported current asthma, compared to only 6% of men [5]. Among adults with asthma, women have a 30% higher mortality rate than men [6]. Disparities that disadvantage women are also evident across a range of other asthma-related outcomes, including disease severity, rescue inhaler use, activity limitations, asthma-related quality of life, and health care utilization [7–12].

Chronic disease self-management refers to the tasks that individuals must carry out in order to minimize the impact of the disease on their daily lives [13]. In the case of asthma, these behaviors—such as medication adherence, identification and management of environmental triggers, and use of an asthma action plan—play a key role in successful asthma control. Limited evidence suggests that women have a tendency to be more adherent to certain aspects of recommended asthma self-care regimens [7,8,14], yet they are also subject to a number of specific challenges in doing so that are linked to both biological sex and socially defined gender roles [15,16]. In this article, we will first review evidence that social roles and status, comorbidities, obesity, hormonal factors, and aging-related changes all shape the context in which women manage their asthma (Table). Next, we will highlight evidence-based asthma self-management support interventions for women that are designed to address some of these factors. Finally, we will offer some tentative conclusions about what is needed to effectively support asthma self-management in women and suggest several potentially fruitful areas for future research in this area.Factors Influencing Asthma Self-Management in Women

Social Roles and Socioeconomic Status

Traditional gender roles involve various responsibilities, such as household cleaning, cooking, and care of young children, that are associated with exposures to precipitants of asthma symptoms [17]. Gender norms also promote the use of personal care products, like fragrances and hair sprays, which are potential asthma triggers [17]. Recent observational studies in Europe have examined the link between women’s use of cleaning products and asthma. Bédard and colleagues [18] found an association between weekly use of cleaning sprays at home and asthma among women, and Dumas and colleagues [19] found that workplace exposure to cleaning products among women with asthma was related to increased symptoms and severity of asthma. These researchers conclude that “while domestic exposure is much more frequent in the general population, exposure levels are probably higher at the workplace” and therefore both contribute to asthma disease burden [19]. Although little-discussed in the literature, sexual activity is another common trigger of asthma symptoms in women. Clark et al [15] found that more than one-third of women taking part in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an asthma self-management intervention reported being bothered by symptoms of asthma during sexual activity. This topic was rarely discussed, however, by their health care providers [20].

Socioeconomic factors also play a significant role in asthma management. There is a well-recognized and persistent gender gap in income in the U.S. population such that women who work full-time only earn three-quarters of what their male counterparts earn [21]. Challenges related to low socioeconomic status (SES) may contribute to poor medication adherence among asthma patients [22]. Although a comprehensive review of the impact of SES-related factors on asthma prevalence, severity, and disease-management behaviors is beyond the scope of this article, recent research demonstrates the impact of financial stress on women’s asthma self-management. Patel et al (2014) studied health-related financial burden among African-American women with asthma [23]. Despite the fact that the majority of women in this qualitative study had health insurance, they felt greatly burdened by out-of-pocket expenses such as high co-pays for medications or ambulance use, lost wages due to sick time, and gaps in insurance coverage. These financial concerns—and related issues such as time spent navigating health care insurance and cycling through private and public insurance programs—were described as a significant source of ongoing stress by this group of vulnerable asthma patients [23]. Focus group participants reported several strategies for dealing with asthma-related financial challenges, including stockpiling medications when feasible (eg, when covered by current insurance plan) for future use by the patient or a family member, seeking out and using community assistance programs, and foregoing medications altogether during periods when they could not afford them [23].

Comorbidities

The 2010 publication of Multiple chronic conditions: a strategic framework by the US Department of Health and Human Services [24] brought the attention of the medical and research communities to the scope and significance of multimorbidity in the US population, including the challenges that individuals face in managing multiple chronic health conditions. Although the prevalence of specific comorbidities with asthma differs by age, some that are most commonly associated with asthma and that may complicate asthma control are obstructive sleep apnea, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), rhinitis, and sinusitis [25,26]. Among women with asthma, multimorbidity appears to be the rule, not the exception. Using nationally-representative data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Patel et al [27] found that more than half of adults with asthma reported also being diagnosed with at least 1 additional major chronic condition. A recent study found that asthma/arthritis and asthma/hypertension were the second and third most prevalent disease dyads among all US women aged 18–44 years [28]. Studies have found that comorbidities among asthma patients are associated with worse asthma outcomes, including increased symptoms, activity limitations and sleep disturbance due to asthma [27], and ED use for asthma [15,27].

Qualitative research yields insight into the patient perspective of multimorbidity, that is, how women with asthma and coexisting chronic diseases perceive the effect of their health conditions on their ability to engage in self-management. Janevic and colleagues [29] conducted face-to-face interviews with African-American women participating in a randomized controlled trial of a culturally and gender-tailored asthma-management intervention to learn about their experiences managing asthma and concurrent health conditions. Interviewees had an average of 5.7 chronic conditions in addition to asthma. Women reported that managing their asthma often “took a backseat” to other chronic conditions. Participants also discussed reduced motivation or capacity for asthma self-management due to depression, chronic pain, mobility limitations or combinations of these, and reduced adherence to asthma medications due to the psychological and logistical burdens of polypharmacy.

Depression and anxiety are common comorbidities that are associated with worse asthma outcomes [26,30–32] and reduced asthma medication adherence [33,34]. In general population studies as well as among asthma patients, women are more likely than men to report depression and anxiety [30,35–37]. Screening for and treating depression and anxiety are indicated in women with asthma and may lead to improved adherence and outcomes [30].