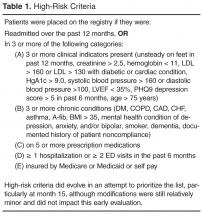

Initially the CCT care managers forwarded the high-risk registry to each provider to review and identify the top patients for proactive care management outreach. CCT care managers then called the identified patients and/or coordinated outreach with patients through office appointments scheduled in the near future. At the same time as the registry outreach began, on-site clinician referrals to the CCT and hospital discharge reconciliation calls to patients by the CCT care manager commenced. Clinician referrals did not have to meet any formal criteria in order for that patient to receive CCT services. Ideally, the program was designed to service high-risk patients on the registry; however, the majority of patient contacts for care management emerged through day-to-day clinician referrals (not necessarily high-risk) and discharge reconciliation calls to high-risk patients for months 2 through 8 of the pilot phase. Patients' care was managed with continued, ongoing services until either patient goals were met or the patient was transferred to another practice or nursing home, expired, or declined further care management assistance. The CCT behavioral health specialist addressed short-term issues or bridged the gap or need until long-term services could be coordinated, sometimes requiring 6 to 8 meetings with a patient. CCT social worker services were assigned on a case-by-case basis and occasionally provided longer-term or intermittent need management, such as medication assistance.

Study Design and Sample

A naturalistic longitudinal study design was used to evaluate the CCT’s preliminary effectiveness. The CCTs were evaluated at 2 levels. First, based on the assumption that the CCT would off-set some of the practice workload and allow the practices to proactively manage more of their patient population, the effectiveness of the CCTs was evaluated at the practice level, ie, patients who did not receive CCT services but belonged to practices with CCTs. Second, the effectiveness of the CCTs was evaluated at the patient level, ie, patients receiving CCT services. At both levels, the CCT groups were contrasted with “non-CCT” comparison groups of convenience.

Participants were 30,287 outpatients (of which 5% were high-risk) from 6 primary care practices served by 2 CCTs. Of these patients, 406 received CCT services (of which 68% were high-risk): 176 care management (CCT-MNGT)and 230 hospital discharge reconciliation calls (CCT-DCREC). CCT-MNGT patients may have received a hospital discharge reconciliation phone call as part of their management. The comparison group for the practice level analyses (all patients from CCT practices that were not engaged with CCT, n = 29,881) included 22,350 patients (of which 5% were high-risk) from 3 non-CCT practices which were also transforming towards PCMH. While these 3 comparison practices were specifically selected due to their involvement in PCMH endeavors and use of disease registries, no other formal matching criteria were utilized. At the practice level, patient outcomes from 12 months before and after the CCT was introduced into the practice (July 2011–July 2013) were compared with those of patients from the 3 non-CCT practices. The comparison group for the patient level analyses (patients who received CCT services) was patients from the same CCT practice who did not receive CCT services ( Table 2