Survey Results

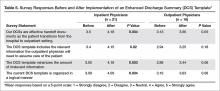

The inpatient provider response rate for the pre-intervention survey was 51/86 (59%) and 33/65 (51%) for the post-intervention survey, resulting in 21 paired responses. House officers represented the majority of paired respondents (14/21, 66%) with hospitalist faculty making up the remainder. Among outpatient physicians, the pre-intervention response rate was 19/25 (76%) and the post-intervention rate was 20/25 (80%), resulting in 16 paired responses. Half (8/16) of outpatient physicians provided only outpatient care, the other half practicing in a traditional model, providing both inpatient and outpatient care. Nearly half (7/16) had been in practice for over 15 years. Inpatient physicians’ agreement with all 4 statements related to discharge summary quality improved, including their perception of discharge summary effectiveness as a handoff document (P = 0.004). Inpatient providers estimated that the enhanced discharge summary took significantly less time to complete (19.3 vs. 24.6 minutes, P = 0.043). Outpatient providers’ perceptions of discharge summary quality trended toward improvement but did not reach statistical significance (Table 5).

Discussion

We found that a restructured note template in combination with physician education can improve discharge summary quality without sacrificing timeliness of note completion, document length, or physician satisfaction. The Joint Commission requires that discharge summaries include condition at discharge, but global assessments such as “good” or “stable” provide little clinically meaningful information to the next provider. Through our enhanced discharge summary we were able to significantly improve communication of several more specific elements relevant to discharge condition, including cognitive status. Similar to prior studies [7,13], cognitive condition was rarely documented prior to our intervention, but improved to 88% after introduction of the enhanced discharge summary. This is especially important, as we found that 25% of the post-intervention patients had a cognitive deficit at discharge. This information is critical for the next provider, who assumes responsibility for monitoring the patient’s trajectory.

Similarly, we improved the inclusion of patient preferences regarding advanced care planning. Whereas code status was rarely included the pre-intervention discharge summaries, we found that 1 in 5 patients in the post-intervention group did not want cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Beyond code status, we were also able to improve documentation of other advanced care conversations, such as end-of-life planning and power-of-attorney assignment. These conversations are increasingly common in the inpatient setting [28] but inconsistently documented [29,30].

To encourage inpatient-outpatient provider communication, the enhanced discharge summary template prompted documentation of communication with the PCP, with a resultant improvement from 25% to 72% (P < 0.001). The template also increased documentation of contact information for the hospital provider from 4% to 95% (P < 0.001). This improvement is notable, as hospital and outpatient physicians communicate infrequently [4,5], despite the fact that direct, “high-touch” communication is often preferred [10,11].

Our intervention builds upon prior research [23,24,31] through its deliberate focus on template formatting, evaluation of comprehensive clinical data elements using clearly defined scoring criteria, inclusion of teaching and non-teaching inpatient services, and assessment of inpatient and outpatient provider satisfaction. By restructuring the enhanced discharge summary template, we were able to improve documentation of clinical information, patient preferences, and physician communication, while keeping notes concise, prioritized, and timely. This restructuring included re-ordering information within the note, adding clear headings, devising intuitive drop-down menus, and removing unnecessary information. The amount of redundant information, document length, and perceived time required to write the discharge summary improved in the post-intervention period. Finally, our intervention was carried out with few resources and without financial incentives.

Although we found overall improvements following our intervention, there were several notable exceptions. Three content areas that were routinely documented in the pre-intervention period showed significant declines in the post-intervention phase: diet, activity, and procedures. Additionally, despite improvements in the post-intervention group, certain elements continued to be unreliably communicated in the discharge summary. Sporadic inclusion of pending tests (47%) was a particularly concerning finding. One possible explanation is that the addition of new elements and a focus on concise documentation encouraged physicians to skip or delete these areas of the enhanced discharge summary. It is also possible that reliance on drop-down menus and manual text entry, rather than auto-populated data, contributed to these deficits. As organizations re-design their electronic note templates, they should consider different content importing options [32] based on local institutional needs, culture, and EHR capabilities [33].

This study had several limitations. It was conducted at a single academic institution, so findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Although the magnitude and specificity of many of the measured outcomes suggests they were caused by the intervention, our pre/post study design cannot rule out the possibility that time-varying factors other than the intervention may have influenced our findings. We also used a novel scoring instrument, as a psychometrically tested discharge summary scoring instrument was not available at the time of the study [34]. Because it was based on similar concepts and evidence, the scoring instrument mirrored the data elements included in the intervention, which may have biased our results away from the null. However, the global rating score, which provided an overall appraisal of discharge summary quality unrelated to specific elements of the intervention, also showed significant improvement following the intervention. The distinct formatting of pre- and post-intervention templates meant that scorers were not blinded, thus making social desirability bias a possibility. We attempted to minimize the risk for bias by having all discharge summaries scored by 2 scorers, including one physician who was not a member of the research team. Small sample sizes, particularly with regard to the outpatient survey, may have contributed to type II errors. Additionally, although the discharge summary education was delivered during required meetings, we did not track attendance, so we were unable analyze for differences between providers who received the education and those that did not. Finally, while we evaluated discharge summaries for inclusion of key information, we did not perform chart reviews or contact PCPs to confirm the accuracy of documented information. Future study should evaluate the sustainability of our intervention and its impact on patient-level outcomes.

In conclusion, we found that revising our electronic template to better function as a handoff document could improve discharge summary quality. While most content areas evaluated showed improvement, there were several elements that were negatively impacted. Hospitals should be deliberate when reformatting their discharge summary templates so as to balance the need for efficient, manageable template navigation with accurate, complete, and necessary information.

Corresponding author: Christopher J. Smith, MD, 986430 Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE 68198-6430 Email: csmithj@unmc.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.