Treatment

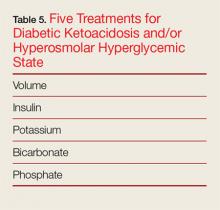

The goal of treatment for DKA and HHS is to correct volume deficits, hyperglycemia, and electrolyte abnormalities (Table 5). Three of the five therapies to manage DKA and HHS are mandatory: IV fluid resuscitation, IV insulin, and IV potassium. The other therapies, IV bicarbonate, and IV phosphate, should be considered, but are rarely required for DKA or HHS.

In general, management of HHS is less aggressive than that of DKA because HHS develops over a period of weeks—unlike DKA, which develops over only 1 to 2 days. Treatment of any underlying causes of HHS should occur simultaneously.

Intravenous Fluids

The goal of IV fluid therapy for patients with DKA is rehydration—not to “wash-out” ketones. Ketone elimination occurs through insulin-stimulated metabolism. When determining volume-replacement goals, it is helpful to keep in mind that patients with moderate-to-mild DKA typically have fluid deficiencies of 3 to 5 L, and patients with severe DKA have fluid deficiencies between 5 and 6 L. Patients with HHS present with significantly higher fluid deficiencies of around 9 to 12 L.

The initial goal of fluid management is to correct hypoperfusion with bolus fluids, followed by a more gradual repletion of remaining deficits. After bolus fluids are administered, the rate and type of subsequent IV fluid infusion varies depending on hemodynamics, hydration state, and serum sodium levels.2,3

Nonaggressive Vs Aggressive Fluid Management. One study by Adrogué et al9 compared the effects of managing DKA with aggressive vs nonaggressive fluid repletion. In the study, one group of patients received normal saline at 1,000 mL per hour for 4 hours, followed by normal saline at 500 mL per hour for 4 hours. The other group of patients received normal saline at a more modest rate of 500 mL per hour for 4 hours, followed by normal saline at 250 mL per hour for 4 hours. The authors found that patients in the less aggressive volume therapy group achieved a prompt and adequate recovery and maintained higher serum bicarbonate levels.9

Current recommendations for patients with DKA are to first treat patients with an initial bolus of 1,000 mL or 20 cc/kg of normal saline. Patients without profound dehydration should then receive 500 cc of normal saline per hour for the first 4 hours of treatment, after which the flow rate may be reduced to 250 cc per hour. For patients with mild DKA, therapy can start at 250 cc per hour with a smaller bolus dose or no bolus dose. Patients with profound dehydration and poor perfusion, should receive crystalloid fluids wide open until perfusion has improved. Overall, volume resuscitation in HHS is similar to DKA. However, the EP should be cautious with respect to total fluid volume and infusion rates to avoid fluid overload, since many patients with HHS are elderly and may have congestive heart failure.

Crystalloid Fluid Type for Initial Resuscitation. Normal saline has been the traditional crystalloid fluid of choice for managing DKA and HHS. Recent studies, however, have shown some benefit to using balanced solutions (Ringer’s lactate or PlasmaLyte) instead of normal saline. A recently published large study by Semler et al10 compared balanced crystalloid, in most cases lactated Ringers solution, to normal saline in critically ill adult patients, some of whom were diagnosed with DKA. The study demonstrated decreased mortality (from any cause) in the group who received balanced crystalloid fluid therapy and reduced need for renal-replacement therapy and reduced incidence of persistent renal dysfunction. The findings by Semler et al10 and findings from other smaller studies, calls into question whether normal saline is the best crystalloid to manage DKA and HHS.11,12 It remains to be seen what modification the American Diabetes Association (ADA) will make to its current recommendations for fluid therapy, which were last updated in 2009.

It appears that though the use of Ringers lactate or PlasmaLyte to treat DKA usually raises a patient’s serum bicarbonate level to 18 mEq/L at a more rapid rate than normal saline, the use of balanced solutions may result in longer time to lower blood glucose to 250 mg/dL.13 However, by using a balanced solution, the hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis often seen with normal saline treatment will be avoided.12

Half-Normal Saline. An initially normal or increased serum sodium level, despite significant hyperglycemia, suggests a substantial free-water deficit. Calculating a corrected serum sodium can help quantify the degree of free-water deficit.3 While isotonic fluids remain the standard for initial volume load, clinicians should consider switching patients to half-normal saline following initial resuscitation if the corrected serum sodium is elevated above normal. The simplest estimation to correct sodium levels in DKA is to expect a decrease in sodium levels at a rate of at least 2 mEq/L per 100-mg/dL increase in glucose levels above 100 mg/dL. For a more accurate calculation, providers can expect a drop in sodium of 1.6 mEq/L per 100 mg/dL increase of glucose up to a level of 400 mg/dL and then a fall of 2.4 mEq/L in sodium per every 100 mg/dL rise in glucose thereafter.14

Glucose. Patients with DKA require insulin therapy until ketoacidosis resolves. However, the average time to correct ketoacidosis from initiating treatment is about 12 hours compared to only 6 hours for correction of hyperglycemia. Since insulin therapy must be continued despite lower glucose levels, patients are at risk for developing hypoglycemia if glucose is not added to IV fluids. To prevent hypoglycemia and provide an energy source for ketone metabolism, patients should be switched to fluids containing dextrose when their serum glucose approaches 200 to 250 mg/dL.1,3 Typically, 5% dextrose in half-normal saline at 150 to 250 cc per hour is usually adequate to achieve this goal.