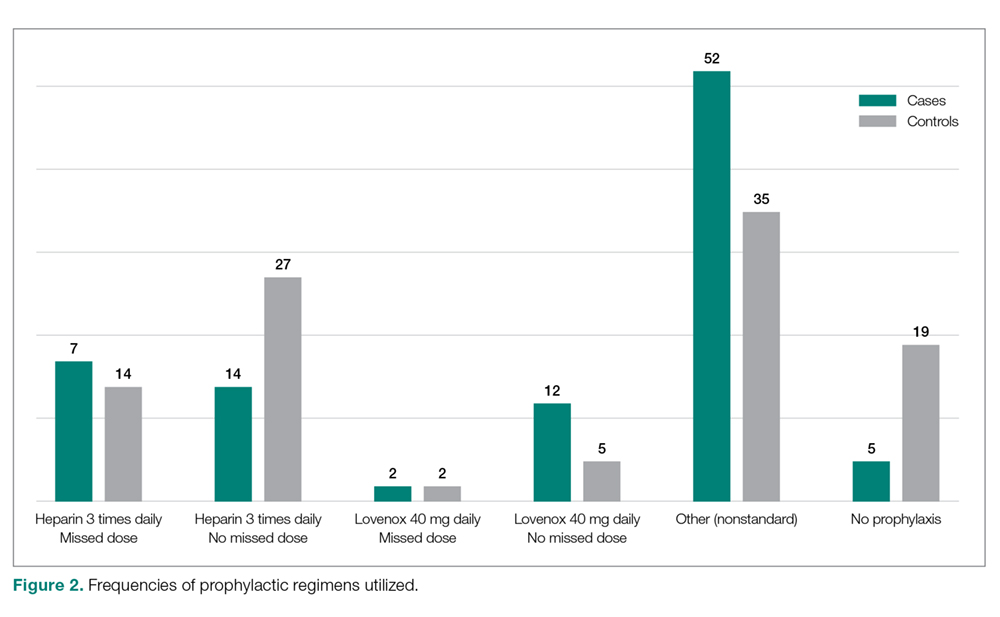

Seventeen cases received heparin on induction during their index procedure, compared to 23 controls (P = 0.24). Additionally, 63 cases began a prophylaxis regimen within 24 hours of surgery end time, compared to 68 controls (P = 0.24). The chemoprophylactic regimens utilized in cases and in controls are summarized in Figure 2. Of note, only 26 cases and 32 controls received standard prophylactic regimens with no missed doses (heparin 5000 units 3 times daily or enoxaparin 40 mg daily). Additionally, in over half of cases and a third of controls, nonstandard regimens were ordered. Examples of nonstandard regimens included nonstandard heparin or enoxaparin doses, low-dose warfarin, or aspirin alone. In most cases, nonstandard regimens were justified on the basis of high risk for bleeding.

Mechanical prophylaxis with pneumatic sequential compression devices (SCDs) was ordered in 93 (91%) cases and 87 (85%) controls; however, we were unable to accurately document uniform compliance in the use of these devices.

With regard to evaluation of our process measures, we found only 17% of cases and controls combined actually had a VTE risk assessment in their chart, and when it was present, it was often incomplete or was completed inaccurately.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to identify factors (patient characteristics and/or processes of care) that may be contributing to the higher than expected incidence of VTE events at our medical center, despite internal audits suggesting near perfect compliance with SCIP-mandated protocols. We found that in addition to usual risk factors for VTE, an overarching theme of our case cohort was their high complexity of illness. At baseline, these patients had significantly greater rates of stroke, thrombophilia, severe lung disease, infection, and history of VTE than controls. Moreover, the hospital courses of cases were significantly more complex than those of controls, as these patients had more procedures, longer lengths of stay and longer index operations, higher rates of postoperative bed rest exceeding 12 hours, and more prevalent central venous access than controls (Table 2). Several of these risk factors have been found to contribute to VTE development despite compliance with prophylaxis protocols.

Cassidy et al reviewed a cohort of nontrauma general surgery patients who developed VTE despite receiving appropriate prophylaxis and found that both multiple operations and emergency procedures contributed to the failure of VTE prophylaxis.11 Similarly, Wang et al identified several independent risk factors for VTE despite thromboprophylaxis, including central venous access and infection, as well as intensive care unit admission, hospitalization for cranial surgery, and admission from a long-term care facility.12 While our study did not capture some of these additional factors considered by Wang et al, the presence of risk factors not captured in traditional assessment tools suggests that additional consideration for complex patients is warranted.