Methods

Setting

The study was conducted on 3 IM nursing units with a total of 83 beds at a large tertiary care academic medical center in the midwestern United States, and was approved by the organization’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included all non-pregnant patients aged 18 years or older who received care from an IM primary service. These patients were admitted directly to an IM team through the emergency department (ED) or transferred to an IM team after an initial stay in the intensive care unit.

Data Source

Microbiology laboratory reports generated from the electronic health record were used to identify all patients with a collected UC sample who received care from an IM service prior to discharge. Urine samples were collected by midstream catch or catheterization. Data on urine Gram stain and urine dipstick were not included. Henceforth, the phrase “urine culture order” indicates that a UC was both ordered and performed. Data reports were generated for the month of August 2016 to determine the baseline number of UCs ordered. Charts of patients with positive UCs were reviewed to determine if antibiotics were started for the positive UC and whether the patient had signs or symptoms consistent with a UTI. If antibiotics were started in the absence of signs or symptoms to support a UTI, the patient was determined to have been unnecessarily treated for ASB. Reports were then generated for the month after each intervention was implemented, with the same chart review undertaken for positive UCs. Bacteriuria was defined in our study as the presence of microbial growth greater than 10,000 CFU/mL in UC.

Interventions

Initial analysis by our study group determined that lack of electronic clinical decision support (CDS) at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs were the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs, respectively. We reviewed the work of other groups who reported interventions to decrease treatment of ASB, ranging from educational presentations to pocket cards and treatment algorithms.8-13 We hypothesized that there would be a decrease in UC orders with CDS embedded in the computerized order entry screen, and that we would decrease unnecessary treatment of positive UCs by educating clinicians on indications for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in the setting of a positive UC.

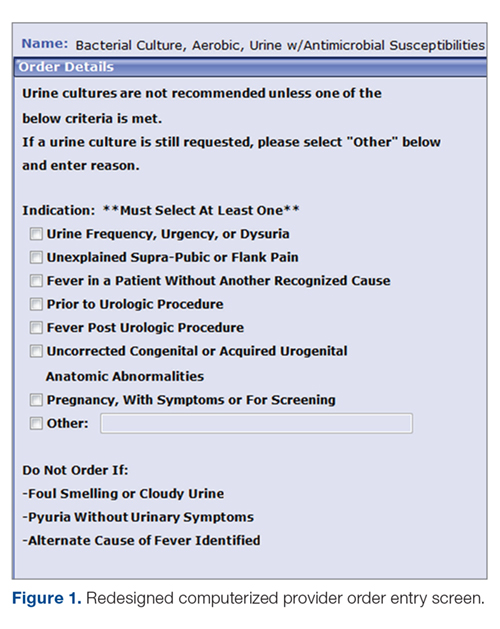

Information technology intervention. The first intervention implemented involved redesign of the UC ordering screen in the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system. This intervention went live hospital-wide, including the IM floors, intensive care units, and all other areas except the ED, on February 1, 2017 (Figure 1). The ordering screen required the prescriber to select from a list of appropriate indications for ordering a UC, including urine frequency, urgency, or dysuria; unexplained suprapubic or flank pain; fever in patients without another recognized cause; screening obtained prior to urologic procedure; or screening during pregnancy. An additional message advised prescribers to avoid ordering the culture if the patient had malodorous or cloudy urine, pyuria without urinary symptoms, or had an alternative cause of fever. Before we implemented the information technology (IT) intervention, there had been no specific point-of-care guidance on UC ordering.

Educational intervention. The second intervention, driven by clinical pharmacists, involved active and passive education of prescribers specifically designed to address unnecessary treatment of ASB. The IT intervention with CDS for UC ordering remained live. Presentations designed by the study group summarizing the appropriate indications for ordering a UC, distinguishing ASB from UTI, and discouraging treatment of ASB were delivered via a variety of routes by clinical pharmacists to nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, medical residents, and staff physicians providing care to patients on the 3 IM units over a 1-month period in March 2017. The presentations contained the same basic content, but the information was delivered to target each specific audience group.

Medical residents received a 10-minute live presentation during a conference. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and staff physicians received a presentation via email, and highlights of the presentation were delivered by clinical pharmacists at their respective monthly group meetings. A handout was presented to nursing staff at nursing huddles, and presentation slides were distributed by email. Educational posters were posted in the medical resident workrooms, nursing breakrooms, and staff bathrooms on the units.