Medical knowledge is growing faster than ever, as is the challenge of keeping up with this ever-growing body of information. Clinicians need a system or method to help them sort and evaluate the quality of new information before they can apply it to clinical care. Without such a system, when facing an overload of information, most of us tend to take the first or the most easily accessed information, without considering the quality of such information. As a result, the use of poor-quality information affects the quality and outcome of care we provide, and costs billions of dollars annually in problems associated with underuse, overuse, and misuse of treatments.

In an effort to sort and evaluate recently published research that is ready for clinical use, the first author (SAS) used the following 3-step methodology:

1. Searched literature for research findings suggesting readiness for clinical utilization published between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019.

2. Surveyed members of the American Association of Chairs of Departments of Psychiatry, the American Association of Community Psychiatrists, the American Association of Psychiatric Administrators, the North Carolina Psychiatric Association, the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, and many other colleagues by asking them: “Among the articles published from July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019, which ones in your opinion have (or are likely to have or should have) affected/changed the clinical practice of psychiatry?”

3. Looked for appraisals in post-publication reviews such as NEJM Journal Watch, F1000 Prime, Evidence-Based Mental Health, commentaries in peer-reviewed journals, and other sources (see Related Resources).

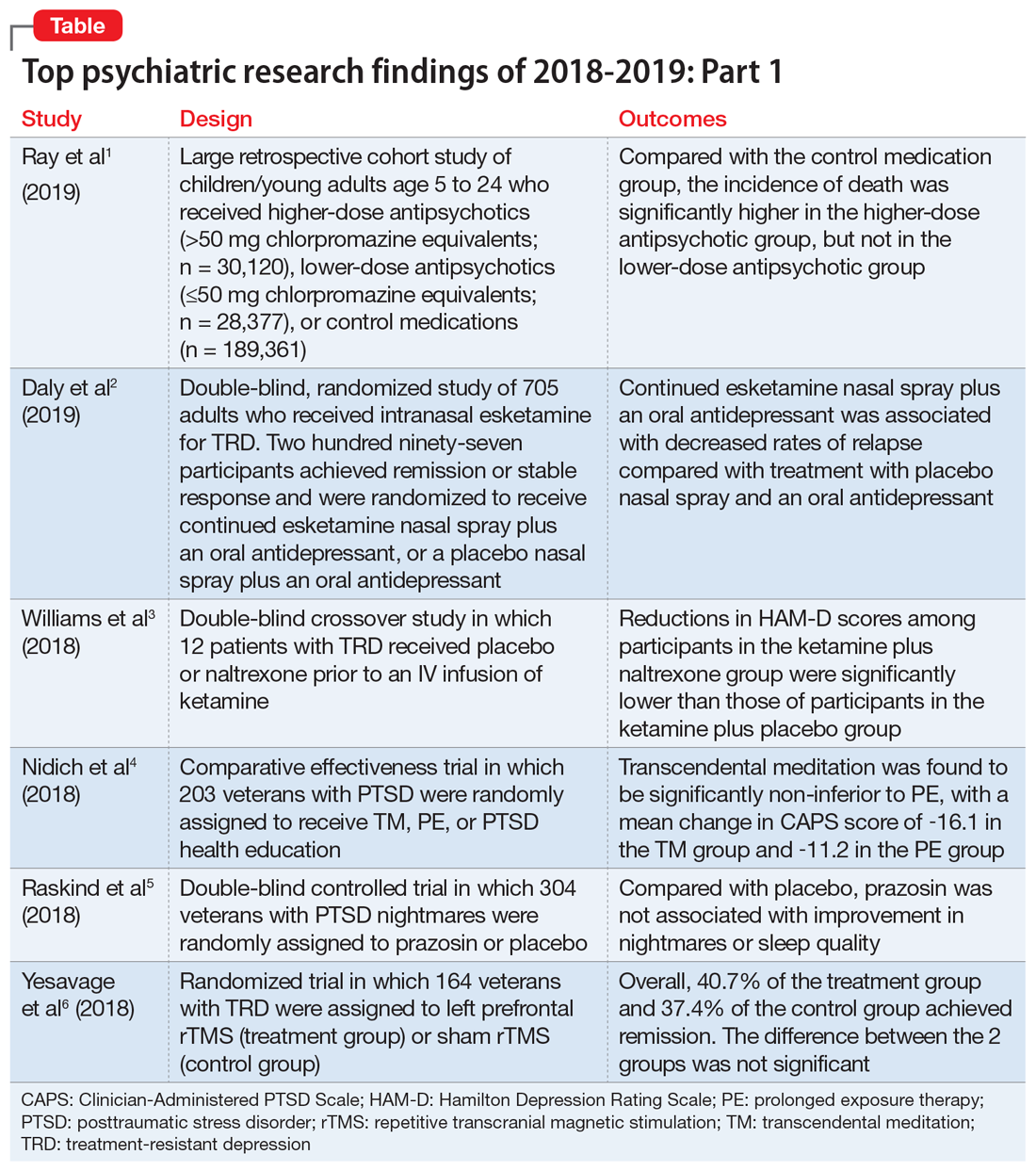

We chose 12 articles based on their clinical relevance/applicability. Here in Part 1 we present brief descriptions of the 6 of top 12 papers chosen by this methodology; these studies are summarized in the Table.1-6 The order in which they appear in this article is arbitrary. The remaining 6 studies will be reviewed in Part 2 in the February 2020 issue of Current Psychiatry.

1. Ray WA, Stein CM, Murray KT, et al. Association of antipsychotic treatment with risk of unexpected death among children and youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):162-171.

Children and young adults are increasingly being prescribed antipsychotic medications. Studies have suggested that when these medications are used in adults and older patients, they are associated with an increased risk of death.7-9 Whether or not these medications are associated with an increased risk of death in children and youth has been unknown. Ray et al1 compared the risk of unexpected death among children and youths who were beginning treatment with an antipsychotic or control medications.

Study design

- This retrospective cohort study evaluated children and young adults age 5 to 24 who were enrolled in Medicaid in Tennessee between 1999 and 2014.

- New antipsychotic use at both a higher dose (>50 mg chlorpromazine equivalents) and a lower dose (≤50 mg chlorpromazine equivalents) was compared with new use of a control medication, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers.

- There were 189,361 participants in the control group, 28,377 participants in the lower-dose antipsychotic group, and 30,120 participants in the higher-dose antipsychotic group.

Outcomes

- The primary outcome was death due to injury or suicide or unexpected death occurring during study follow-up.

- The incidence of death in the higher-dose antipsychotic group (146.2 per 100,000 person-years) was significantly higher (P < .001) than the incidence of death in the control medications group (54.5 per 100,000 person years).

- There was no similar significant difference between the lower-dose antipsychotic group and the control medications group.

Continue to: Conclusion