Benign fibrous histiocytoma (BFH) is a rare, well-recognized, primary skeletal tumor accounting for approximately 1% of all benign bone tumors. Spinal involvement is exceedingly rare with only 11 cases reported in the literature.1,2 We present a case of BFH located in the cervical spine of a pediatric patient that was successfully treated with curretage through an anterior surgical approach, along with a review of the literature and appropriate management concerning BFH of the spine.

Case Report

A 14-year-old boy was tackled while playing football and noticed immediate neck pain and subjective paresthesia in the upper extremities. Examination revealed a nontender spine (cervical, thoracic, lumbar) and normal strength and range of motion in all extremities. Sensation was diffusely intact, long tract signs were absent, and gait was normal. On questioning, the patient endorsed mild antecedent neck pain but denied prior history of any trauma. Neck pain did not radiate and was slightly worsened by activity but was mostly intermittent and random. As the neck pain was very mild and was not interfering with daily activities, the patient had not sought care before presenting to the emergency department. He had no pertinent past medical or surgical history.

The patient presented with a computed tomography (CT) scan of his head and cervical spine and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the cervical spine. A magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) scan of the neck was ordered after his arrival.

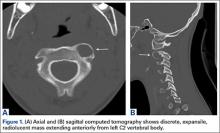

Axial and sagittal CT (Figures 1A, 1B) showed a 1×1.2-cm discrete, expansile, lytic, radiolucent mass extending anterior from the left C2 vertebral body. The mass appeared to abut the left vertebral artery foramen. The cortical bone surrounding the lesion was thin but uniform. Sagittal and axial T1-weighted MRI (Figures 2A, 2B) showed the discrete, expansile, homogenous lesion with the same intensity as normal bone marrow. Sagittal and axial T2-weighted MRI (Figures 2C, 2D) showed a discrete, expansile, homogenous lesion with primarily high signal intensity. Sagittal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) MRI (Figure 2E) again showed the lesion with primarily low intensity. Given the close proximity of the lesion to the vertebral foramen, MRA was ordered; it showed the lesion was not interfering with the vertebral artery (Figure 2F).

The tumor’s location, in the left anterior aspect of the C2 vertebral body, was not conducive to percutaneous biopsy for establishing tissue diagnosis, so the decision was made to surgically excise the lesion. A left-sided anterior incision was made 2 fingerbreadths inferior to the jaw line in a neck crease. A head and neck surgeon assisted with dissection. Dissection was carried down through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and platysma on to the anterior part of the spine medial to the carotid sheath. Superior thyroid nerve and vessels and superior laryngeal nerve were identified and preserved. Fluoroscopy confirmed correct location at C2. The tumor was easily visualized, and the outer shell broke easily with palpation. Gentle curettage was necessary when removing the tumor off the vertebral artery. A portion of the specimen was sent during surgery for frozen section, which showed infrequent mitotic figures and no other findings concerning for malignancy. No instability was created after curettage and excision of the tumor, so no grafting or instrumentation was necessary.

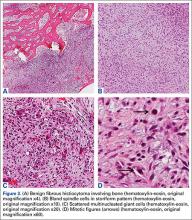

Grossly, the tumor was pale tan and firm. Histologic examination with hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed a bland spindle-cell neoplasm that focally involved bone. A storiform pattern was present. The cells had scant cytoplasm and oval to elongate nuclei with tapered ends. Significant nuclear pleomorphism was not seen. The stroma was loose, with focal myxoid change. Benign multinucleated giant cells were present. Mitotic activity was infrequent (Figures 3A–3D). Two attending pathologists reviewed the case material and the frozen and formalin-fixed specimens independently and concurred with the diagnosis of BFH. In addition, the case was reviewed at the surgical pathology consensus conference; the reviewers agreed on BFH, and additional studies were deemed unnecessary.

Given the patient’s complete clinical picture, the differential diagnosis included nonossifying fibroma (NOF), eosinophilic granuloma (EG), BFH, fibrous dysplasia, giant cell tumor (GCT), aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC), and osteoblastoma (OB).

Discussion

BFH is an extremely rare bone lesion, accounting for only 1% of all surgically managed bone tumors; not counting the present case, only 11 spine cases have been reported in the literature.1,2 BFH of the spine traditionally causes nonspecific, poorly localized pain. The Table lists the reported cases of spinal BFH and their presenting symptoms, location, and treatment. BFH usually occurs in young adults, but the age range is 5 to 75 years.2-4 Mean age of the 12 patients with spinal BFH in the literature (including ours) is 25 years.1 In addition, spinal BFH appears to have no predilection for sex.