The variety of employment models available to gastroenterologists reflects the dynamic changes we are experiencing in medicine today. Delivery of gastrointestinal (GI) care in the United States continues to evolve in light of health care reform and the Affordable Care Act.1 Within the past decade, as health systems and payers continue to consolidate, regulatory pressures have increased steadily and new policies such as electronic documentation and mandatory quality metrics reporting have added new challenges to the emerging generation of gastroenterologists.2 Although the lay press tends to focus on health care costs, coverage, physician reimbursement, provider burnout, health system consolidation, and value-based payment models, relatively less has been published about emerging employment and practice models.

Here,

Background

When the senior author graduated from fellowship in 1983 (J.I.A.), gastroenterology practice model choices were limited to essentially 4: independent community-based, single-specialty, physician-owned practice (solo or small group); independent multispecialty physician-owned practice; hospital or health system–owned multispecialty practice; and academic practice (including the Veterans Administration Medical Centers).

In the private sector, young community gastroenterologists typically would join a physician-owned practice and spend time (2–5 y) as an employed physician in a partnership track. During this time, his/her salary was subsidized while he/she built a practice base. Then, they would buy into the Professional Association with cash or equity equivalents and become a partner. As a partner, he/she then had the opportunity to share in ancillary revenue streams such as facility fees derived from a practice-owned ambulatory endoscopy center (AEC). By contrast, young academic faculty would be hired as an instructor and, if successful, climb the traditional ladder track to assistant, associate, and professor of medicine in an academic medical center (AMC).

In the 1980s, a typical community GI practice comprised 1 to 8 physicians, with most having been formed by 1 or 2 male gastroenterologists in the early 1970s when flexible endoscopy moved into clinical practice. The three practices that eventually would become Minnesota Gastroenterology (where J.I.A. practiced) opened in 1972. In 1996, the three practices merged into a single group of 38 physicians with ownership in three AECs. Advanced practice nurses and physician assistants were not yet part of the equation. Colonoscopy represented 48% of procedure volume, accounts receivable (time between submitting an insurance claim and being paid) averaged 88 days, and physicians averaged 9000 work relative value units (wRVUs) per partner annually. By comparison, median wRVUs for a full-time community GI in 1996 was 10,422 according to the Medical Group Management Association.3 Annual gross revenue (before expenses) per physician was approximately $400,000, and overhead reached 38% and 47% of revenue (there were 2 divisions). Partner incomes were at the 12% level of the Medical Group Management Association for gastroenterologists (personal management notes of J.I.A.). Minnesota Gastroenterology was the largest single-specialty GI practice in 1996 and its consolidation foreshadowed a trend that has accelerated over the ensuing generation.

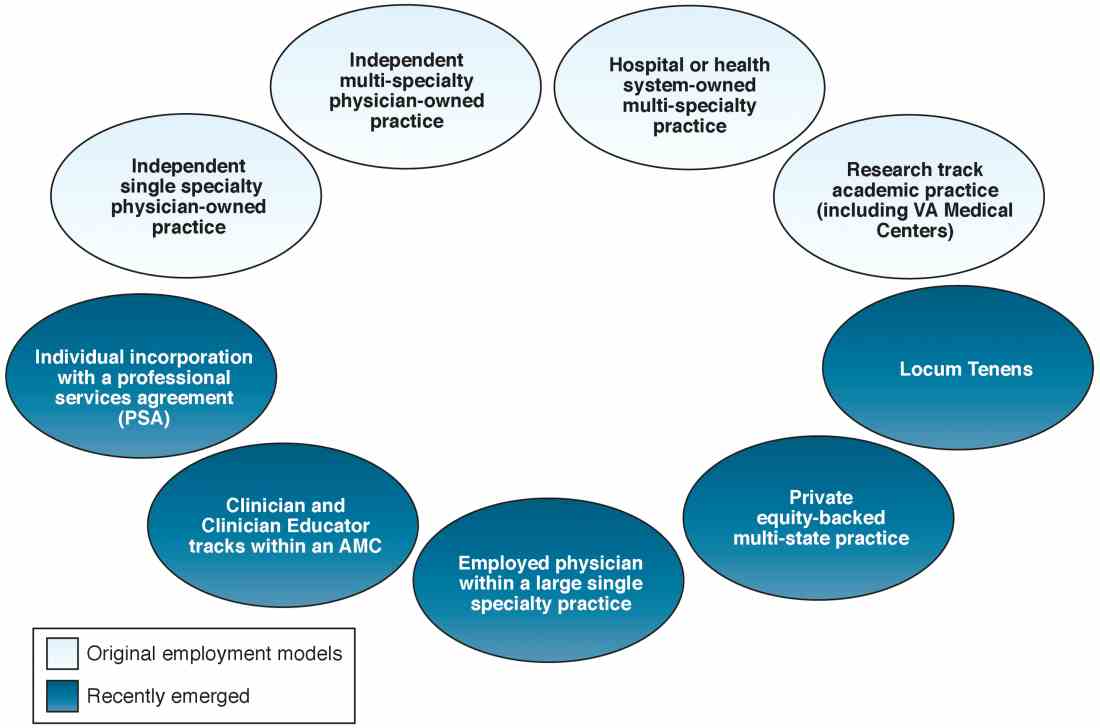

When one of the authors (N.K.) graduated from the University of California Los Angeles in 2017, the GI employment landscape had evolved considerably. At least five new models of GI practice had emerged: individual incorporation with a Professional Services Agreement (PSA), a clinician track within an AMC, large single-specialty group practice (partnership or employee), private equity-backed multistate practice, and locum tenens (Figure 1).

Employment models (light blue) available in the 1980s and those that have emerged as common models in the last decade (dark blue).

An individual corporation with a professional services agreement

For gastroenterologists at any career stage, the prospect of employment within a corporate entity, be it an academic university, hospital system, or private practice group, can be daunting. To that end, one central question facing nearly all gastroenterologists is: how much independence and flexibility, both clinically and financially, do I really want, and what can I do to realize my ideal job description?

An interesting alternative to direct health system employment occurs when a physician forms a solo corporation and then contracts with a hospital or health system under a PSA. Here, the physician provides professional services on a contractual basis, but retains control of finances and has more autonomy compared with employment. Essentially, the physician is a corporation of one, with hospital alignment rather than employment. For full disclosure, this is the employment model of one of the authors (N.K.).

A PSA arrangement is common for larger independent GI practices. Many practices have PSA arrangements with hospitals ranging from call coverage to full professional services. For an individual working within a PSA, income is not the traditional W-2 Internal Revenue Service arrangement in which taxes are removed automatically. Income derived from a PSA usually falls under an Internal Revenue Service Form 1099. The physician actually is employed through their practice corporation and relates to the hospital as an independent contractor.

There are four common variants of the PSA model.4 A Global Payment PSA is when a hospital contracts with the physician practice for specific services and pays a global rate linked to wRVUs. The rate is negotiated to encompass physician compensation, benefits, and practice overhead. The practice retains control of its own office functions and staff.