Editor's Note:

The Case Challenge series includes difficult-to-diagnose conditions, some of which are not frequently encountered by most clinicians but are nonetheless important to accurately recognize. Test your diagnostic and treatment skills using the following patient scenario and corresponding questions. If you have a case that you would like to suggest for a future Case Challenge, please contact us .

Background

A 58-year-old woman seeks medical attention after she discovered a new mass in her left axilla during a routine monthly breast self-examination while showering. She has not noted any changes in either of her breasts. The mass in her left axilla is not tender, and she has not felt any other abnormal masses, including in her right axilla. She reports no other symptoms and specifically has no pain anywhere in her body. She also does not have shortness of breath, fever, night sweats, fatigue, rash, or abdominal discomfort or bloating.

Fifteen years earlier, the patient was diagnosed with high-grade, stage 1 cervical cancer and underwent surgery and chemoradiation. She has been closely monitored since that time with physical examinations and abdominal CT, with no evidence of recurrent disease. The patient has not had any other surgical procedure, except for removal of two basal cell carcinomas on her neck 4 years ago. She has had yearly routine mammograms for at least the past 15 years.

The patient has hypertension, which has been well controlled with the same medications for the past 10 years. She also has a 25-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, which is currently managed with diet alone. She had a "silent myocardial infarction" sometime within the past 5 years but has had no cardiac symptoms and is not taking any cardiac medications. She smoked approximately one pack of cigarettes a day for less than 2 years when she was "in her teens" but has not had any tobacco products since that time.

Pancreatic cancer was diagnosed in the patient's father at age 49 years, and breast cancer was diagnosed in her aunt on her father's side at age 67 years. Her paternal grandmother is reported to have died in her 60s after diagnosis of a "cancer in her stomach." No further information is available regarding either the actual diagnosis or the medical care provided to this individual.

To the best of the patient's knowledge, her mother's side of the family and her two brothers have no history of cancer. She has no sisters. Her mother is in her 80s and has mild dementia. The patient is not aware of any member of her family having undergone genetic testing.

Physical Examination and Workup

The patient appears well and is in no acute distress. The patient is afebrile, with a blood pressure of 135/85 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min, and a pulse of 72 beats/min. Her weight is 148 lb (67 kg), and she has no reported recent weight loss.

Examination of the skin reveals no suspicious lesions. Scars from the previous removal of the basal cell carcinomas are noted, but no evidence suggests recurrence.

Results of the head and neck examination are unremarkable; specifically, no abnormal cervical lymphadenopathy is detected. The cardiac and chest examination results are normal. The lungs are clear to percussion and auscultation. The breast examination reveals no abnormal masses. The right axilla is unremarkable; however, a single 3 × 2 cm, nontender, firm, movable but partially fixed mass is noted in the left axilla.

The abdomen appears normal, with no ascites or enlargement of the liver. The pelvic examination reveals evidence of previous surgery and local radiation but no signs of recurrence of cervical cancer. The lymph nodes appear normal, except for the findings noted above. Results of the neurologic examination are unremarkable.

Complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte levels, renal function tests, and urinalysis are all normal. Liver function tests are normal except for a mildly elevated serum alkaline phosphatase level. The fecal occult blood test result is negative.

Chest radiography reveals a suspicious small left-sided pleural effusion. No other abnormalities are observed, and no prior chest radiographs are available to compare with the current findings.

Chest CT confirms the presence of a possible small pleural effusion, with no other abnormalities noted. The radiologist suggests it will not be possible to obtain fluid safely through an interventional procedure, owing to the limited (if any) amount of fluid present. Furthermore, the radiologist recommends PET/CT to look for other evidence of metastatic cancer in the lungs or elsewhere.

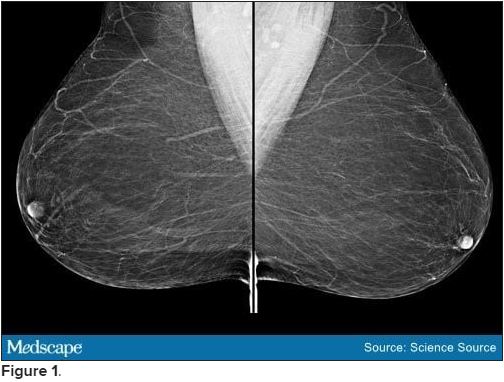

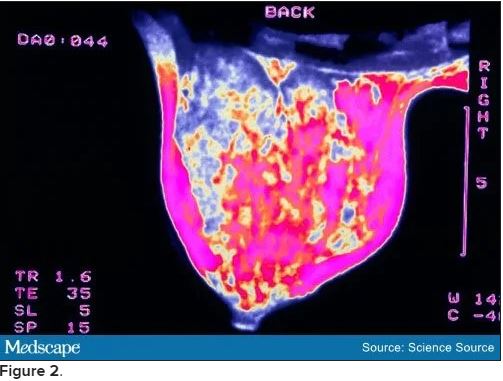

Bilateral mammograms reveal no suspicious abnormalities, and the results are unchanged from a previous examination 11 months earlier. Figure 1 shows a similar bilateral mammogram in another patient. Breast MRI shows no evidence of cancer. Figure 2 shows similar breast MRI findings in another patient.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis reveals no changes compared with a scan obtained 2 years earlier for follow-up of the previous diagnosis of cervical cancer. Specifically, no evidence suggests ascites or any pelvic masses.

An incisional biopsy sample is obtained from the left axillary mass. Light microscopy reveals a moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Immunostaining shows the cancer to be cytokeratin (CK) 7 positive and CK 20 negative (CK 7+/CK 20-, thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) negative, thyroglobulin negative, napsin A negative, and mammaglobin positive. The tumor is estrogen receptor positive (2% staining), progesterone receptor negative, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative.

Discussion

The correct answer: Breast.

This case is a classic example of cancer of unknown primary site or origin (CUP). CUP represents approximately 5% of cancers diagnosed in the United States (50,000 to 60,000 cases each year), with various series reporting that the site of origin is not diagnosed in between 2% and 6% of all cancer cases.[1] Worldwide, the incidence of CUP is even higher, resulting from the limited availability of sophisticated (and expensive) diagnostic technology in many regions. The median age at diagnosis of CUP is 60 years, and men and women are equally likely to be affected.

A cancer is considered a CUP if, after routine clinical assessment, physical and laboratory examination, standard imaging studies, and routine pathologic evaluation (biopsy or surgical removal of a metastatic mass lesion), a site of origin cannot be defined. With the availability of more sophisticated imaging technologies (eg, MRI), the overall percentage of cancers that are defined as a CUP has been reduced. However, even at autopsy, the site of origin of such cancer is often unable to be determined if the location was unknown before the patient's death.

Several theories have been proposed for why a metastatic lesion becomes clinically evident despite the site of origin of the cancer remaining obscure. These include (1) very slow growth of the primary cancer compared with that of the metastasis; (2) spontaneous regression of the primary cancer; (3) a prominent vascular component of the cancer, which enhances the rate of spread; and (4) unique molecular events associated with the cancer, which result in rapid progression and the growth of metastatic lesions.

Approximately 60% of CUPs are adenocarcinomas (well or moderately well differentiated); 25%-30% are poorly differentiated (including poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas); 5% are completely undifferentiated, with no defining histologic features; 5% are squamous cell cancers; and approximately 1% are carcinomas, with evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation.[1]

Immunohistochemical staining of biopsy material can be helpful in narrowing the possible anatomical sites of origin. The results are particularly relevant in the selection of therapeutic strategies and in ensuring that a rare, potentially highly curable cancer is not missed (eg, lymphoma, germ cell tumor).[2]

A critical initial test is examination of several CK subtypes that are more likely to be expressed in certain carcinomas than in others. For example, the CK 7+/CK 20- staining seen in this patient is characteristic of breast and lung cancers (among others), whereas CK 7+/CK 20+ staining would be expected in pancreatic, gastric, and urothelial cancers. A CK 7-/CK 20+ finding would be more suggestive of colon or mucinous ovarian cancer. Furthermore, approximately 70% of lung adenocarcinomas are TTF-1 positive and 60%-80% are napsin A positive. The negative findings in this patient's case make the diagnosis of metastatic lung cancer less likely.

Examination for the presence (or absence) of well-established biomarkers for breast cancer can potentially be helpful in suggesting the site of origin or in helping to define subsequent therapy. These markers include estrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2 overexpression. An additional biomarker, mammaglobin, has been reported to be expressed in 48% of breast cancers but is absent in cancers of the lung, gastrointestinal tract, ovary, and head and neck region.[2]

Of note, mammaglobin was found to be expressed in this patient. Although only 2% of the cells were reported to stain for the estrogen receptor, this finding is still considered positive and supports breast cancer as the correct diagnosis.

Recognized relevant prognostic factors in CUP include baseline performance status, the number and location of metastatic lesions, and the response to cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Unfortunately, the overall prognosis associated with a diagnosis of CUP is poor, with median survival in various series reported to be less than 6 months. However, important exceptions to this outcome include women who present with an isolated metastatic axillary mass, as described in this case.

Previous reports of axillary adenopathy as the initial presentation of cancer in women revealed that the majority had evidence of cancer in the breast at the time of subsequent mastectomy.[3,4] As a result, in the absence of other indications found during routine workup (eg, a single pulmonary lesion suggestive of a primary lung cancer, pathologic findings inconsistent with breast cancer), an isolated adenocarcinoma in the breast (with no evidence of metastatic cancer elsewhere) should be treated as either stage II or stage III breast cancer. Note that this recommendation specifically relates to female patients. If a male patient has CUP with an isolated axillary mass, it is generally assumed that the lung is the origin of the malignancy.

In a female patient with negative mammographic findings, breast MRI can be helpful. In one series, 28 of 40 women (70%) with evidence of cancer in the axilla and a normal mammogram were found to have a breast abnormality on MRI.[5] Of note, and of considerable relevance to subsequent disease management, five of the 12 women with negative findings in this series underwent surgery, and in four of the cases no cancer was found. Although the number of participants in this series is limited, the absence of an MRI abnormality in the patient in this case can reasonably be considered in her future treatment plans.

Specifically, it might be suggested in this case that treatment include surgical removal of the axillary mass (if possible) followed by radiation to this area and the breast (rather than performing a mastectomy). Alternatively, treatment might begin with chemotherapy (a neoadjuvant approach) followed by surgery to remove any residual axillary mass and local/regional radiation or local/regional radiation alone. Adjuvant chemotherapy and/or hormonal therapy would then be administered.

The presence of a possible small pleural effusion is a concern because it potentially indicates more widespread metastatic disease, as does the mild elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase level (eg, suggesting metastatic disease in bone or the liver). In the absence of other evidence of tumor spread, PET would not be unreasonable. A negative scan for evidence of metastatic disease would support a "curative" approach to the management of local disease in the axilla and presumably the breast, whereas a finding of other metastatic sites would lead to the conclusion that treatment should probably be delivered with more palliative intent.

The family history of cancer (father, paternal aunt with breast cancer, paternal grandmother with possible ovarian cancer) is intriguing and would suggest a role for genetic counseling and possibly genetic testing (eg, for BRCA mutation).

The patient in this case underwent PET. The only abnormality observed was in the left axilla. The axillary mass was subsequently resected. This was followed by curative radiation to both the axilla and left breast, adjuvant chemotherapy, and 5 years of hormonal therapy. The patient has showed no evidence of recurrence 2 years after completion of the hormonal treatment.

Discussion

The correct answer: Lung

The lungs are generally assumed to be the site of origin of the cancer in a male patient who has CUP with an isolated axillary mass. In contrast, the majority of women with axillary adenopathy as the initial presentation of cancer were found to have evidence of cancer in the breast at the time of subsequent mastectomy.[3,4]

Discussion

The correct answer: MRI

Breast MRI can be helpful in a female patient with negative mammographic findings. In one series, MRI detected a breast abnormality in 28 of 40 women (70%) with evidence of cancer in the axilla and a normal mammogram.[5]