The term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) refers to the bothersome symptoms and physical findings associated with estrogen deficiency that involve the labia, vestibular tissue, clitoris, vagina, urethra, and bladder.1 GSM is associated with genital irritation, dryness, and burning; urinary symptoms including urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections; and sexual symptoms including vaginal dryness and pain. Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) represents a component of GSM.

GSM is highly prevalent, affecting more than three-quarters of menopausal women. In contrast to menopausal vasomotor symptoms, which often are most severe and frequent in recently menopausal women, GSM commonly presents years following menopause. Unfortunately, VVA symptoms may have a substantial negative impact on women’s quality of life.

In this 2020 Menopause Update, I review a large observational study that provides reassurance to clinicians and patients regarding the safety of the best-studied prescription treatment for GSM—vaginal estrogen. Because some women should not use vaginal estrogen and others choose not to use it, nonhormonal management of GSM is important. Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton provides details on a randomized clinical trial that compared the use of fractionated CO2 laser therapy with vaginal estrogen for the treatment of GSM. In addition, Dr. JoAnn Manson discusses recent studies that found lower health risks with vaginal estrogen use compared with systemic estrogen therapy.

Diagnosing GSM

GSM can be diagnosed presumptively based on a characteristic history in a menopausal patient. Performing a pelvic examination, however, allows clinicians to exclude other conditions that may present with similar symptoms, such as lichen sclerosus, Candida infection, and malignancy.

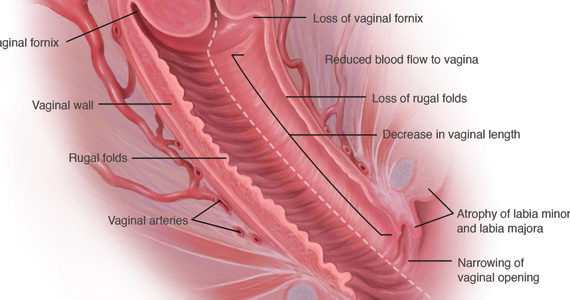

During inspection of the external genitalia, the clinician may note loss of the fat pad in the labia majora and mons as well as a reduction in labia minora pigmentation and tissue. The urethral meatus often becomes erythematous and prominent. If vaginal or introital narrowing is present, use of a pediatric (ultrathin) speculum reduces patient discomfort. The vaginal mucosa may appear smooth due to loss of rugation; it also may appear shiny and dry. Bleeding (friability) on contact with a spatula or cotton-tipped swab may occur. In addition, the vaginal fornices may become attenuated, leaving the cervix flush with the vaginal apex.

GSM can be diagnosed without laboratory assessment. However, vaginal pH, if measured, is characteristically higher than 5.0; microscopic wet prep often reveals many white blood cells, immature epithelial cells (large nuclei), and reduced or absent lactobacilli.2

Nonhormonal management of GSM

Water, silicone-based, and oil-based lubricants reduce the friction and discomfort associated with sexual activity. By contrast, vaginal moisturizers act longer than lubricants and can be applied several times weekly or daily. Natural oils, including olive and coconut oil, may be useful both as lubricants and as moisturizers. Aqueous lidocaine 4%, applied to vestibular tissue with cotton balls prior to penetration, reduces dyspareunia in women with GSM.3

Vaginal estrogen therapy

When nonhormonal management does not sufficiently reduce GSM symptoms, use of low-dose vaginal estrogen enhances thickness and elasticity of genital tissue and improves vaginal blood flow. Vaginal estrogen creams, tablets, an insert, and a ring are marketed in the United States. Although clinical improvement may be apparent within several weeks of initiating vaginal estrogen, the full benefit of treatment becomes apparent after 2 to 3 months.3

Despite the availability and effectiveness of low-dose vaginal estrogen, fears regarding the safety of menopausal hormone therapy have resulted in the underutilization of vaginal estrogen.4,5 Unfortunately, the package labeling for low-dose vaginal estrogen can exacerbate these fears.

Continue to: Nurses’ Health Study report...