CASE Broken down

Ms. E, age 20, is a college student who has had major depressive disorder for several years and a genetic bone disease (osteogenesis imperfecta, mixed type III and IV). She presents with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. She reports recent worsening of her depressive symptoms, including anhedonia, excessive sleep, difficulty concentrating, and feeling overwhelmed, hopeless, and worthless. She also describes frequent thoughts of suicide with the plan of putting herself in oncoming traffic, although she has no history of suicide attempts.

Previously, her primary care physician prescribed lorazepam, 0.5 mg, as needed for anxiety, and sertraline, 100 mg/d, for depression and anxiety. She experienced only partial improvement in symptoms, however.

In addition to depressive symptoms, Ms. E describes manic symptoms lasting for as long as 3 to 5 days, including decreased need for sleep, increased energy, pressured speech, racing thoughts, distractibility, spending excessive money on cosmetics, and risking her safety—given her skeletal disorder— by participating in high-impact stage-combat classes. She denies auditory and visual hallucinations, homicidal ideation, and delusions.

The medical history is significant for osteogenesis imperfecta, which has caused 62 fractures and required 16 surgeries. Ms. E is a theater major who, despite her short stature and wheelchair use, reports enjoying her acting career and says she does not feel demoralized by her medical condition. She describes overcoming her physical disabilities with pride and confidence. However, her recent worsening mood symptoms have left her unable to concentrate and feeling overwhelmed with school.

Ms. E is voluntarily admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder with rapid cycling, most recent episode mixed. Because of her bone fragility, the treatment team considers what would be an appropriate course of drug treatment to control bipolar symptoms while minimizing risk of bone loss.

Which medications are associated with decreased bone mineral density?

a) citalopram

b) haloperidol

c) carbamazepine

d) paliperidone

e) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a genetic condition caused by mutations in genes implicated in collagen production. As a result, bones are brittle and prone to fracture. Different classes of psychotropics have been shown to increase risk of bone fractures through a variety of mechanisms. Clinicians often must choose appropriate pharmacotherapy for patients at high risk of fracture, including postmenopausal women, older patients, malnourished persons, and those with hormonal deficiencies leading to osteoporosis.

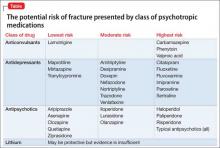

To assist our clinical decision-making, we reviewed the literature to establish appropriate management of a patient with increased bone fragility and new-onset bipolar disorder. We considered all classes of medications used to treat bipolar disorder, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, and anticonvulsants.

Antipsychotics

In population-based studies, prolactin-elevating antipsychotics have been associated with decreased bone mineral density and increased risk of fracture.1 Additional studies on geriatric and non-geriatric populations have supported these findings.2,3

The mechanism through which fracture risk is increased likely is related to antipsychotics’ effect on serum prolactin and cortisol levels. Antipsychotics act as antagonists on D2 receptors in the hypothalamic tubero-infundibular pathway, therefore preventing inhibition of prolactin. Long-term elevation in serum prolactin can cause loss of bone mineral density through secondary hypogonadism and direct effects on target tissues. Additional modifying factors include smoking and estrogen use.

The degree to which antipsychotics increase fracture risk might be related to the degree of serum prolactin elevation.4 Antipsychotics previously have been grouped by the degree of prolactin elevation, categorizing them as high, medium, and low or no potential to elevate serum prolactin.4 Based on this classification, typical antipsychotics, risperidone, and paliperidone have the highest potential to elevate prolactin. Accordingly, antipsychotics with the lowest fracture risk are those that have the lowest risk of serum prolactin elevation: ziprasidone, asenapine, quetiapine, and clozapine. Aripiprazole may lower prolactin in some patients. This is supported by studies noting reduced bone mineral density5,6 and increased risk of fracture1 with high-potential vs low- or no-potential antipsychotics. Because of these findings, it is crucial to consider the potential risk of prolactin elevation when treating patients at increased risk of fracture. Providers should consider low/no potential antipsychotic medications before considering those with medium or high potential (Table).

Antidepressants

In a meta-analysis, antidepressants were shown to increase fracture risk by 70% to 90%.2 However, the relative risk varies by antidepressant class. Several studies have shown that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are associated with a higher risk of fracture compared with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).7 In addition, antidepressants with a high affinity for the serotonin transporter, including citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, and imipramine, have been associated with greater risk of osteoporotic fracture compared with those with low affinity.8

The mechanisms by which antidepressants increase fracture risk are complex, although the strongest evidence implicates a direct effect on bone metabolism via the 5-HTT receptor. This receptor, found on osteoblasts and osteoclasts, plays an important role in bone metabolism; it is through this receptor that SSRIs might inhibit osteoblasts and promote osteoclast activity, thereby disrupting bone microarchitecture. Additional studies are needed to further describe the mechanism of the association among antidepressants, bone mineral density, and fracture risk.