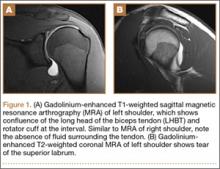

Three years after his initial visit, the patient returned to the office with a similar complaint of pain and limitation of function in his left shoulder after returning to full athletic competition. Once again, there was no history of injury, and history, physical examination, and MRI arthrogram (Figures 1A, 1B) evaluation proved to be very similar to this young athlete’s right shoulder work-up.

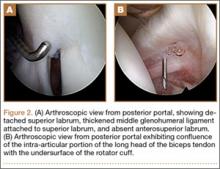

The patient once again underwent shoulder arthroscopy and treatment. Although this was now the left shoulder, the findings were essentially identical to the right shoulder. Once again, the labrum was detached from the 11-o’clock to 2-o’clock positions, and a Buford complex was present anteriorly (Figure 2A). The labral tear was easily displaceable from the glenoid with a probe, and placing the shoulder through a range of motion led to increased displacement of the labrum from the glenoid. There was also confluence of the intra-articular LHBT with the undersurface of the capsule within the rotator interval (Figure 2B). A radiofrequency wand, shaver, and elevator were used to define the biceps tendon and separate it from the undersurface of the capsule. The SLAP repair was performed using three 2.9-mm absorbable suture anchors with 2 posterior and 1 anterior to the biceps tendon insertion. The labral repair was observed while placing the shoulder through range of motion and the shoulder was seen to be free of any undue tension on the labrum.

Postoperatively, the patient’s sling and rehabilitation protocol was identical to that of the right shoulder. The patient progressed well, was released to full activity at 6 months, and has not returned with any further complaints of left or right shoulder pain. Approximately 3 years after treatment the patient was contacted via phone and asked about symptoms, pain, and activity. He denies current symptoms of clicking or instability and has no pain that he can identify as being related to previous pathology or treatment. Since the surgery, he has ceased competitive sports and weight lifting, which he attributes to deconditioning associated with postsurgical immobilization and lack of motivation.

Discussion

Of the 8 case reports in the literature that identified variable intra-articular biceps insertional anatomy, only 2 reports represented confluence of the biceps within the rotator interval.7 Interestingly, of the cases identified, the single case that presented a patient with similar pathology of a type II SLAP lesion had an almost identical anatomical variant presentation consisting of both the anomalous insertion of the LHBT into the undersurface of the rotator interval and a Buford variant of the anterosuperior glenohumeral ligament complex. To our knowledge, our bilateral case of an altered intra-articular biceps insertion and a concomitant SLAP tear supports the theory that this pattern of anomalous insertion may very well have altered the biomechanics of the tendon, resulting in acquired pathology to the superior labrum.

The literature reviewed showed the prevalence of anatomic variations of the LHBT ranged from 1.9% to 7.4%.13,14 These variations are generally considered benign; however, in some cases—as in the cases of the young athletes presented by Wahl and MacGillivray7 and in this report—anatomic variation may play an important role in pathogenesis of different injury patterns. The primary function of the LHBT is the stabilization of the glenohumeral joint during abduction and external rotation.15 When the insertion diverges from normal (eg, when the tendon is tethered to the undersurface of the rotator cuff), the biomechanical stresses on the tendon likely change. As a result of the anomalous position of the LHBT origin, there may be a change in the shoulder joint’s biomechanics, with increased strain on the glenohumeral ligament and its attachment onto the glenoid.16

This case report differs from publications on variable superior glenohumeral ligament attachments because a discrete superior glenohumeral ligament structure was isolated from the biceps tendon. Although a larger case series or patient cohort, as well as more involved biomechanical analysis, would certainly be necessary to prove our hypothesis, we believe that this case suggests certain anatomic LHBT and labral variations can contribute to the develop of SLAP tears in younger individuals.