Isolated brachialis muscle atrophy has been rarely reported. Among the few cases in the literature, 1 was attributed to a presumed compartment syndrome,1 1 to a displaced clavicle fracture,2 and 3 to neuralgic amyotrophy.3,4 We present a case of isolated brachialis muscle atrophy of unknown etiology, the presentation of which is consistent with neuralgic amyotrophy, also known as Parsonage-Turner syndrome or brachial plexitis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 37-year-old right-handed highway worker presented for evaluation of right-arm muscle atrophy. One year earlier, while lifting heavy bags at work, he felt a painful strain in his right arm, although there was no bruising or swelling. Approximately 4 weeks after this incident, he developed right shoulder pain and began to notice a slight decrease in the muscle mass of his right anterior arm. On evaluation at an outside facility, the physician noted some brachialis muscle atrophy. His shoulder pain was attributed to acromioclavicular joint problems. After an initial trial of physical therapy that did not alleviate this joint pain, an acromioclavicular joint resection was performed, and his pain improved. The brachialis muscle atrophy continued to progress, however. Over the course of the next 6 months, the patient noticed a continually decreasing muscle mass in his right arm, as well as arm fatigue with routine recreational activities. On follow-up, again at an outside institution, the treating physicians noted continued atrophy of the distal arm corresponding to the region of the brachialis musculature. Magnetic resonance imaging showed continuity of the brachialis muscle and tendon, with muscle atrophy. The patient was able to return to work, although with a subjective decrease in right elbow flexion strength.

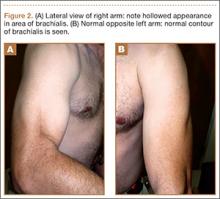

On presentation at our institution, the patient complained of right arm weakness with heavy use but did not have pain or sensory complaints. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable. Physical examination revealed obvious wasting of the right brachialis muscle, most notable on the lateral aspect of the distal arm (Figures 1, 2A, 2B). His biceps muscle was functioning with full strength and had a normal bulk. He had a normal range of active and passive motion, including full extension and flexion of both elbows, as well as complete pronosupination of the forearms. There was no focal tenderness. Manual muscle testing of both upper extremities was completely normal except for 4/5 flexion strength of the right elbow. Neurovascular examination also revealed normal findings, including intact sensation over the radiolateral forearm. A second magnetic resonance image showed that the brachialis muscle had completely atrophied. Because the clinical examination and imaging studies both indicated isolated brachialis atrophy without deficit elsewhere along the musculocutaneous nerve, electromyography was not performed. The patient was fully functional and working at his usual occupation, and no further intervention was recommended.

Discussion

Isolated wasting of the brachialis muscle is extremely rare with few reports in the literature. Farmer and colleagues1 reported a case of brachialis atrophy that was presumed to have resulted from exercise-induced chronic compartment syndrome. In that case, the patient developed a prodrome of arm pain followed by brachialis muscle atrophy. This patient was treated with oral anti-inflammatory agents with improvement in pain but without recovery of the brachialis muscle. While this case was attributed to compartment syndrome, it is likely that it represented neuralgic amyotrophy because there was no evidence of elbow flexion contracture, which would have accompanied true necrosis of the brachialis muscle as seen in compartment syndrome. However, acute compartment syndrome of the brachialis muscle after minor trauma has been reported.5 In that case, full-scale compartment syndrome was treated with rapid fasciotomy, with complete recovery of the brachialis.

Isolated brachialis atrophy has also been described in the setting of a displaced midshaft clavicle fracture in an elite athlete.2 Two fracture fragments were thought to have injured the brachial plexus, separately causing brachialis atrophy and altered sensation over the clavicular head of the deltoid muscle. Atrophy remained 1 year after injury.

Although it had been occasionally reported, the first large series of patients with sporadic neuralgic amyotrophy in the upper extremity was reported by Parsonage and Turner6 in 1948. They described 136 patients who developed flaccid paralysis and atrophy of various muscles of the shoulder girdle and/or upper extremity. This was generally preceded by acute pain in the shoulder girdle, often associated with antecedent viral infection, stress, illness, or other precipitating factors.

To our knowledge, there have been 3 other reported cases of neuralgic amyotrophy of the brachialis muscle. Watson and colleagues3 presented 2 patients with nonspecific, neurogenic shoulder pain after which an indolent, progressive atrophy of the brachialis muscle ensued.3 Van Tongel and colleagues4 described a more traditional case of Parsonage-Turner syndrome, with bilateral wasting of the shoulder girdle that also exhibited unilateral brachialis atrophy without affecting other muscles in the arm.4 Our case, with shoulder pain followed by muscle atrophy, fits the pattern of neuralgic amyotrophy.