Take-Home Points

- Hip capsule provides static stabilization for the hip joint.

- Capsular management must weigh visualization to address underlying osseous deformity but also repair/plication of the capsule to maintain biomechanical characteristics.

- T-capsulotomy provides optimal visualization with a small interportal incision with a vertical incision along the femoral neck.

- Extensile interportal capsulotomy is the most widely used capsulotomy and size may vary depending on capsular and patient characteristics.

- Orthopedic surgeons should be equipped to employ either technique depending on the patients individual hip pathomorphology.

Hip arthroscopy has emerged as a common surgical treatment for a number of hip pathologies. Surgical treatment strategies, including management of the hip capsule, have evolved. Whereas earlier hip arthroscopies often involved capsulectomy or capsulotomy without repair, more recently capsular closure has been considered an important step in restoring the anatomy of the hip joint and preventing microinstability or gross macroinstability.

The anatomy of the hip joint includes both static and dynamic stabilizers designed to maintain a functioning articulation. The osseous articulation of the femoral head and acetabulum is the first static stabilizer, with variations in offset, version, and inclination of the acetabulum and the proximal femur. The joint capsule consists of 3 ligaments—iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral—that converge to form the zona orbicularis. Other soft-tissue structures, such as the articular cartilage, the labrum, the transverse acetabular ligament, the pulvinar, and the ligamentum teres, also provide static constraint.1 The surrounding musculature provides the hip joint with dynamic stability, which contributes to overall maintenance of proper joint kinematics.

Management of the hip capsule has evolved as our understanding of hip pathology and biomechanics has matured. Initial articles on using hip arthroscopy to treat labral tears described improvement in clinical outcomes,2 but the cases involved limited focal capsulotomy. Not until the idea of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) was introduced were extensive capsulotomies and capsulectomies performed to address the underlying osseous deformities and emulate open techniques. Soon after our ability to access osseous pathomorphology improved with enhanced visualization and comprehensive resection, cases of hip instability after hip arthroscopy surfaced.3-5 Although frank dislocation after hip arthroscopy is rare and largely underreported, it is a catastrophic complication. In addition, focal capsular defects were also described in cases of failed hip arthroscopy and thought to lead to microinstability of the hip.6 Iatrogenic microinstability is thought to be more common, but it is also underrecognized as a cause of failure of hip arthroscopy.7Microinstability is a pathologic condition that can affect hip function. In cases of recurrent pain and unimproved functional status after surgery, microinstability should be considered. In an imaging study of capsule integrity, McCormick and colleagues6 found that 78% of patients who underwent revision arthroscopic surgery after hip arthroscopic surgery for FAI showed evidence of capsular and iliofemoral defects on magnetic resonance angiography. Frank and colleagues8 reported that, though all patients showed preoperative-to-postoperative improvement on outcome measures, those who underwent complete repair of their T-capsulotomy (vs repair of only its longitudinal portion) had superior outcomes, particularly increased sport-specific activity.

For patients undergoing hip arthroscopy, several predisposing factors can increase the risk of postoperative instability. Patient-related hip instability factors include generalized ligamentous laxity, supraphysiologic athletics (eg, dance), and borderline or true hip dysplasia. Surgeon-related factors include overaggressive acetabular rim resection, excessive labral débridement, and lack of capsular repair.5,9 Although there are multiple techniques for accessing the hip joint and addressing capsular closure at the end of surgery,9-14 we think capsular closure is an important aspect of the case.

Surgical Technique

For a demonstration of this technique, click here to see the video that accompanies this article. The patient is moved to a traction table and placed in the supine position. Induction of general anesthesia with muscle relaxation allows for atraumatic axial traction. The anesthetized patient is assessed for passive motion and ligamentous laxity. Well-padded boots are applied, and a well-padded perineal post is used for positioning. Gentle traction is applied to the contralateral limb, and axial traction is applied through the surgical limb with the hip abducted and minimally flexed. The leg is then adducted and neutrally extended, inducing a transverse vector cantilever moment to the proximal femur. The foot is internally rotated to optimize femoral neck length on an anteroposterior radiograph. The circulating nursing staff notes the onset of hip distraction in order to ensure safe traction duration.

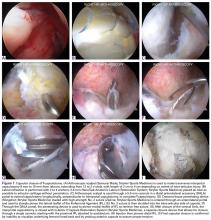

Bony landmarks are marked with a sterile marking pen. Under fluoroscopic guidance, an anterolateral (AL) portal is established 1 cm proximal and 1 cm anterior to the AL tip of the greater trochanter. Standard cannulation allows for intra-articular visualization with a 70° arthroscope. A needle is used to localize placement of a modified anterior portal. After cannulation, the arthroscope is placed in the modified anterior portal to confirm safe entry of the portal without labral violation. An arthroscopic scalpel (Samurai Blade; Stryker Sports Medicine) is used to make a transverse interportal capsulotomy 8 mm to 10 mm from the labrum and extending from 12 to 2 o’clock; length is 2 cm to 4 cm, depending on the extent of the intra-articular injury (Figure 1A).

The capsule adjacent to the acetabulum is exposed from the anterior inferior iliac spine (2 o’clock) anteromedially to the direct head of the rectus femoris origin posterolaterally (12 o’clock).The acetabular rim is trimmed with a 5.0-mm arthroscopic burr. Distal AL accessory (DALA) portal placement (4-6 cm distal to and in line with the AL portal) allows for suture anchor–based labral refixation. Generally, 2 to 4 anchors (1.4-mm NanoTack Anatomic Labrum Restoration System; Stryker Sports Medicine) are placed as near the articular cartilage as possible without penetration (Figure 1B). On completion of labral refixation, traction is released, and the hip is flexed to 20° to 30°.