Results

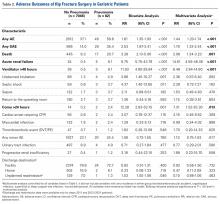

Of the 7128 geriatric hip fracture patients in this study, 82 (1.2%) had active pneumonia at time of surgery (Table 1). Age, BMI, preoperative uremia, history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, renal disease, and smoking were similar between groups. In addition, there was no difference in anesthesia type or fixation procedure between the pneumonia and no-pneumonia groups. Patients with preoperative pneumonia differed significantly with respect to sex, transfer from facility, preoperative functional dependence, anemia, confusion, dyspnea at rest, and history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Table 1).

Interval from admission to surgery was longer (P < .001) for geriatric hip fracture patients with preoperative pneumonia (mean, 6.8 days; 95% CI, 2.5-11.1 days) than for those without pneumonia (mean, 1.5 days; CI, 1.4-1.5 days). There was no difference (P = .124) in operative time between the pneumonia group (mean, 72.8 min; CI, 64.0-81.5 min) and the no-pneumonia group (mean, 66.1 min; CI, 61.2-67.0 min). Interval from surgery to discharge was longer (P < .001) for patients with preoperative pneumonia (mean, 10.1 days; CI, 6.9-13.4 days) than for those without pneumonia (mean, 6.3 days; CI, 6.1-6.4 days).

Adverse outcomes of geriatric hip fracture surgery are listed in Table 2. In the multivariate analysis, preoperative pneumonia was significantly associated with any AE (relative risk [RR]) = 1.44) and any SAE (RR = 1.79).

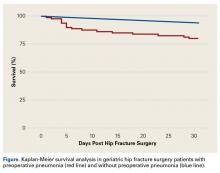

Specific AEs were also assessed. In terms of SAEs, patients with pneumonia were more likely to die (RR = 2.08), develop acute renal failure (RR = 14.61), become comatose for more than 24 hours (RR = 7.31), and require mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours after surgery (RR = 6.48). In terms of minor AEs, there were no significant differences between patients with and without pneumonia.Survival patterns diverged between patients with and without preoperative pneumonia (Figure). The unadjusted mortality rate was qualitatively higher in patients with preoperative pneumonia than in patients without pneumonia during the first days after hip fracture (slopes of unadjusted mortality curves in Figure). Of note, no patient under age 75 years with pneumonia at time of surgery died within the 30-day study period.

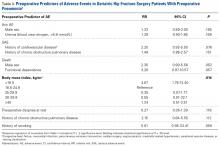

Among geriatric hip fracture patients with preoperative pneumonia, multivariate analyses revealed no significant association of any preoperative comorbidity with any AE or any SAE. Given the gravity of the death complication, however, death within 30 days after surgery was analyzed separately, and was found to be significantly associated (RR = 4.67) with being underweight (BMI, <18.5 kg/m2) (Table 3). Admission-to-surgery interval longer than 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours did not reach significance at the P < 0.2 level in the stepwise regressions and therefore was not associated with a higher or lower risk of any AE, SAE, or death.

Discussion

In the general US population, pneumonia accounts for 1.4% of deaths in people 65 years to 74 years old, 2.1% in people 75 years to 84 years, and 3.1% in people 85 years or older. In total, 3.4% of hospital inpatient deaths are attributed to pneumonia.25 In hospitalized general orthopedic surgical patients as well as hip fracture patients, pneumonia is strongly associated with increased mortality.26,27

We identified a preoperative pneumonia prevalence of 1.2%, which is comparable to the rates reported in the literature (0.3%-3.2%).1-3 To our knowledge, our study represents the largest series of patients with preoperative pneumonia at time of hip fracture repair, and the first to independently associate preoperative pneumonia with increased incidence of AEs, including death.

This study had its limitations. First, the ACS-NSQIP morbidity and mortality data, which are limited to the first 30 postoperative days, may be skewed because AEs that occurred after that interval are not captured. Second, coding of pneumonia in ACS-NSQIP does not convey specific information about the disease and its severity—infectious organism(s) responsible; acquisition setting (healthcare or community); treatment given, including antibiotic(s) selection, steroid use, dosing, and duration; and measures of treatment efficacy—limiting interpretation of the difference in delay to surgery. We cannot say whether the longer interval in patients with pneumonia reflects medical optimization, or whether the delay itself or any interventions during that time positively or negatively affected outcomes. In addition, despite using a large national database, we obtained a relatively small sample of patients (82) who had pneumonia before surgical hip fracture repair.

Multivariate analysis controlling for baseline demographics and comorbidities revealed that multiple SAEs were independently associated with preoperative pneumonia (overall SAE, RR = 1.79). Postoperative use of ventilator support for longer than 48 hours (RR = 6.48) and coma longer than 24 hours (RR = 7.31) are expected given the severity of pulmonary compromise in the study cohort.28,29 Acute renal failure (RR = 14.61) can occur in both hip fracture patients and community-acquired pneumonia patients and may be a multifactorial complication of the pulmonary infection, of the anesthesia, or of the surgical intervention in this cohort.30-32Unadjusted mortality in hip fracture takes months to a year to normalize to that of age-matched controls.32-34 In our series, the unadjusted death rate in the pneumonia cohort (Figure) was transiently elevated during the first weeks after surgery but then drew nearer the rate in the nondiseased hip fracture cohort by the end of the first month. Early death in the pneumonia group likely was multifactorial, potentially influenced by the increased burden of comorbidities in the pneumonia group at baseline, and the longer delay to surgery,35-38 as well as by the natural history of treated pneumonia in hospital patients, who, compared with age-matched hospitalized controls, also exhibit higher mortality during only the first 2 to 4 months of hospitalization for pneumonia.39 We regret that quality improvement strategies in the treatment of geriatric hip fracture surgery with pneumonia cannot be extrapolated from these results.

Similarly, the utility of BMI <18.5 kg/m2 as an actionable preoperative finding cannot be assessed from these results. However, we propose that underweight geriatric hip fracture patients with pneumonia may benefit from more aggressive preoperative optimization that does not delay surgery. Higher acuity of postoperative care, including more intensive nursing care and early coordination of care with respiratory therapists and medical comanagement teams, may also be beneficial.

Anesthesia type did not differ between patients with and without preoperative pneumonia and was not associated with AEs in patients with preoperative pneumonia. Consistent with our findings, multiple studies have reported no significant differences in short-term outcomes of hip fracture repair between general and spinal anesthesia, though no other study has compared the benefits of general and spinal anesthesia for patients with preoperative pneumonia.40-44 Although spinal anesthesia (relative to general anesthesia) has been reported to have benefits in hip and knee arthroplasty, these benefits appear not to translate to hip fracture repair.45-50 The results of the present study suggest that general and spinal anesthesia may be equivalent in terms of risk for the geriatric hip fracture patient with preoperative pneumonia.43,44Our attempt to evaluate the CURB-65 pneumonia severity score as a prognosticator of AEs was thwarted by the absence of required variables in the ACS-NSQIP dataset (confusion, uremia, dyspnea, and age were available; hypotension and blood pressure were not). In our analysis, we did include, individually, variables previously found to predict AEs in the medical pneumonia population (confusion, uremia, dyspnea at rest, anemia).9-11,32 However, these clinical findings are nonspecific in hip fracture patients, who may become anemic, confused, dyspneic, or uremic from a multitude of factors related to their injury and unrelated to pneumonia, including but not limited to hemorrhage, muscle damage, renal injury, and pulmonary embolism. It is not surprising that confusion, uremia, dyspnea at rest, and anemia were not individually predictive of AEs or death within 30 days after surgery in the cohort of geriatric hip fracture patients with pneumonia.

There is no literature that argues for or against delaying hip fracture surgery in geriatric hip fracture patients with pneumonia. The surgical delay observed in this population is ostensibly related to medical optimization of the pneumonia and/or underlying comorbidities. However, we did not find a morbidity or mortality detriment or benefit in delaying surgery by 1 to 4 days in this population. Delay of surgery is a poor covariate, given extensive confounding by medical management and preoperative optimizing of comorbid conditions (reflected in our independent variable and covariates) as well as institutional and surgeon variations in policy and behavior and other unaccounted influences. Although some authors have found no difference in mortality or major AEs between hip fracture patients who had a surgical delay and those who did not,31,51-53 other series and meta-analyses have suggested a mortality detriment in a surgical delay of more than 2 days36,54 or 4 days55 from admission. Given our data, we cannot recommend against immediate hip fracture repair in the subpopulation of geriatric hip fracture patients with pneumonia.

Our study findings suggest that preoperative pneumonia is a rare independent risk factor for AEs after hip fracture surgery in geriatric patients. Underweight BMI is predictive of death in geriatric hip fracture surgery patients who present with pneumonia, whereas early surgical repair appears not to be associated with adverse outcomes. Further investigation is warranted to determine if such patients benefit from specific preoperative and postoperative strategies for optimizing medical and surgical care based on these findings.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):E177-E185. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.