Results

ARCR Outcomes

After ARCR, there was significant improvement in patient-reported pain and subjective strength scores. Mean (SD) pain score improved from 5.9 (2.3) to 1.3 (2.3) after ARCR (P < .001), and mean (SD) strength improved from 46% (22%) of normal to 84% (17%) of normal (P < .001).

Importance of Post-ARCR Pain Relief and Strength Return

Analysis of preoperative questionnaire responses

revealed that, of 60 patients, 29 (48.3%) considered pain relief and strength return equally important, 20 (33.3%) valued postoperative strength return was more important, and 11 patients (18.3%) rated pain relief was more important than strength return. After a mean (SD) follow-up of 5.2 (0.2) years, 33 patients (55 %) valued pain relief and strength return as equally important, 17 patients (28.3%) preferred a strength recovery, and 10 patients (16.7%) preferred pain relief.

Overall patient ratings were significantly higher for strength return compared to pain relief before surgery, mean (SD), 9.2 (2.1) and 8.6 (2.3) (P = .02), and afterward, 8.9 (1.9) and 8.2 (3.1) (P = .03) (Table 1).

Although SPD was lower after surgery (relative increase in importance of analgesia at postoperative time point), the value was not significant (P = .73). There was a weak positive correlation between patient-reported preoperative pain and importance of pain relief ratings (r = 0.05, P < .001), but there was no significant correlation between postoperative values (r = 0.01, P = .73). Also, there was no significant correlation between importance of strength return rating and strength deficits reported before surgery (r = 0.22, P = .09) or afterward (r = 0.21, P = .11).Subgroup Analyses

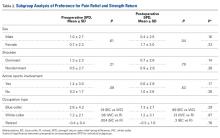

Sex and Age. Of the 60 patients, 43 were male and 17 female. Mean (SD) preoperative SPD was 1.0 (2.7) for males and 0.7 (2.3) females; the difference was not significant (P = .61). After surgery, females emphasized strength return over pain relief more than males did: Mean (SD) SPD was significantly higher (P = .04) for females, 1.7 (3.0), than for males, 0.4 (2.5). There were no preoperative–postoperative differences (P = .33) for males or females (Table 2).

Before surgery, increasing age was associated with lower SPD, indicating a stronger preference for pain relief over strength return (r = 0.33, P = .01). There was no association between age and SPD after surgery (r = 0.2, P = .12).Hand Dominance. RCT was found in the dominant shoulder of 31 patients (52%). Shoulder dominance did not affect SPD: Mean (SD) preoperative SPD was 1.3 (2.3) for dominant shoulders and 0.5 (2.7) for nondominant shoulders (P = .21), and postoperative SPD was 0.7 (2.6) for dominant and 0.9 (2.8) for nondominant (P = .79). SPD did not change from before surgery to after surgery for dominant (P = .14) or nondominant (P = .28) shoulders (Table 2).

Active Sports Participation. Thirty-two patients (53%) reported preoperative involvement in sports; 35 (58%) reported postoperative involvement (P = .37). Mean (SD) preoperative SPD was 1.4 (3.0) for involved patients and 0.3 (1.7) for uninvolved patients (P = .09), and postoperative SPD was 0.6 (2.8) for involved patients and 1.0 (2.6) for uninvolved patients (P = .53). SPD did not change from before surgery to after surgery for involved (P = .17) or uninvolved (P = .26) patients (Table 2).

Occupation Type. There were 9 blue-collar workers (15%), 32 white-collar workers (53%), and 19 retirees (32%). Mean (SD) preoperative SPD was 2.8 (4.2) for blue-collar workers, 1.2 (2.1) for white-collar workers, and –0.4 (0.4) for retirees. There were no significant differences in preoperative SPD between blue-collar and white-collar workers (P = .19) or between white-collar workers and retirees (P = .06), but there was a significant difference between blue-collar workers and retirees (P = .004). Mean (SD) postoperative SPD was 1.3 (2.7) for blue-collar workers, 1.2 (3.1) for white-collar workers, and –0.3 (1.6) for retirees. There were no significant differences between blue-collar and white-collar workers (P = .99), white-collar workers and retirees (P = .13), or blue-collar workers and retirees (P = .3).

Discussion

In this study, we wanted to determine patients’ pre- and postoperative preferences for pain relief and strength return after ARCR. Preoperative and postoperative preference analysis of the 60 patients who underwent ARCR revealed that the majority valued pain relief and strength return equally. However, overall, there was higher ratings for strength return in long term after ARCR, irrespective of age, sex, preoperative levels of shoulder pain and weakness, and preoperative and postoperative sports involvement.

Patients’ preoperative expectations are a function of their assessment of their symptoms, their perceptions of expected surgical outcomes, and their understanding of preoperative discussion with their surgeons. In this study, patients self-assessed their shoulder symptoms and their effect on their occupational and personal life. They also rated the importance of post-ARCR pain relief and strength return relative to each other. To assess whether surgical outcomes affected perceptions of pain relief and strength return, patients completed the questionnaire before and after surgery. Overall, patients rated postoperative strength return over pain relief on long-term (5 years).

Subgroup analysis revealed a weak positive correlation between patient-reported preoperative pain scores and ratings of the importance of pain relief after surgery, but there was no correlation between postoperative pain scores and ratings of the importance of pain relief after surgery. This finding was surprising because we thought pain relief would be more important than strength return for patients with higher pain scores.1-3,16-21 We would like to clarify a point about this study: That patients preferred strength return over pain relief does not mean they did not care about pain relief. A substantial subset of patients (~50%) valued pain relief and strength return equally. In rotator cuff pathology, pain and weakness are to an extent interrelated. Shoulder pain that limits a patient’s ability to perform a strenuous task can be perceived as shoulder weakness, which may explain why, despite having higher pain scores, patients preferred strength return over pain relief. Increasing age showed a positive correlation with preference for pain relief, which explains the finding that retirees preferred pain relief over strength return. We used SPD to express the preference for strength return over pain relief before and after ARCR. Unfortunately, SPD may not be used to quantitatively define the preference for strength return over pain relief.

Patient satisfaction after RCR involves multiple factors and has been well studied. In a retrospective analysis of 112 patients, Tashjian and colleagues10 found that patient satisfaction was affected by preoperative expectations, marital status, disability status, preoperative pain function, and general health status after RCR. They also found a positive but weak correlation between patient satisfaction and functional outcome scores, including visual analog scale (VAS), Simple Shoulder Test (SST), and Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) scores. Henn and colleagues11 evaluated 125 patients who underwent primary RCR for a chronic RCT. Higher preoperative expectations correlated with better postoperative VAS, SST, DASH, and Short Form 36 performance, irrespective of worker compensation status, symptom duration, number of patient comorbidities, tear size, repair technique, and number of previous operations. In a prospective cohort analysis of 311 RCR patients, O’Holleran and colleagues12 found that decreased patient satisfaction was associated with postoperative pain and dysfunction. Furthermore, willingness to recommend surgery to another person was significantly related to patient satisfaction. In the present study, we did not correlate preoperative expectations with postoperative outcome scores or evaluate the effect of other known factors on RCR outcomes. Our main goal was to understand ARCR patients’ preoperative and postoperative evaluations of the importance of pain relief and strength return relative to each other. Improved understanding of patients’ expectations will allow us to identify disparities between expectations and outcomes.

Our study had several limitations. First, our questionnaire was not validated. However, we used it only as an assessment tool, to collect data, and do not propose using it to assess ARCR outcomes. Second, objective strength measurements were not performed, before or after surgery, and therefore patients’ perceptions of weakness were not tested. Third, we did not correlate preoperative or postoperative shoulder outcome scores with patients’ expectations. Our intention was to understand how ARCR patients rate the importance of pain relief and strength return relative to each other. Fourth, we did not correlate patients’ expectations of strength return and pain relief with preoperative tear size or postoperative retear status.

Our observational study results showed that, before undergoing ARCR, most patients valued postoperative pain relief and strength return equally. However, there was an overall preference for strength return over pain relief. Furthermore, this preference held up irrespective of age, sex, sports involvement, or preoperative symptom severity. These findings add to our understanding of patients’ preoperative expectations of ARCR.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(4):E244-E250. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.