Several other classification schemes exist. Jordan and colleagues24 described a classification scheme defining a meniscal type as complete or incomplete, also noting the presence of symptoms, tearing, and peripheral rim instability. They grouped stable types together, regardless of morphology, and then further classified them based on the presence of symptoms and tears. Similarly, the unstable types were grouped together and then subclassified in the same manner.17,24 Klingele and colleagues25 also described a contemporary classification scheme of discoid meniscus evaluating peripheral stability patterns that may be more clinically and surgically relevant. This classification is based on the type of discoid morphology (complete vs incomplete), the presence or absence of peripheral rim stability (stable vs unstable), and the presence or absence of a meniscal tear (torn vs untorn).5,25

EVALUATION

A stable discoid meniscus is often an incidental finding, seen either on advanced diagnostic imaging performed for another reason or at the time of arthroscopy to address another problem. Younger children with discoid meniscus tend to present with symptoms such as popping and snapping related to instability and the abnormal morphology of the discoid meniscus. Older patients tend to present with symptoms related to acute tears through the abnormal meniscal tissue. Although discoid menisci can become acutely symptomatic in the presence of a tear, the onset of symptoms may occur in the absence of a discrete traumatic event.1 Alternatively, some patients will report a clear history of injury, often a noncontact, rotational injury mechanism related to an athletic activity. Patients with torn discoid menisci may report pain, catching, locking, and/or giving way of the knee, and on examination may have limited extension, snapping, effusion, quadriceps atrophy, and joint line tenderness. Eponymous meniscal compression tests including the McMurray, Apley, and Thessaly tests, may also be performed when meniscal tear is suspected, although this may be tricky for younger children.1

Considering the high association of meniscal tears with ligamentous injuries, examination of knee stability is important. Plain radiographs of the knee should be taken, although the results will often be negative for osseous injury in the case of an isolated meniscal tear. Radiographs of a discoid knee may show subtle differences compared with radiographs of a non-discoid knee. A recent comparison of children with symptomatic lateral discoid menisci with age-matched controls found statistically significant increased lateral joint space, elevated fibular head, increased height of the lateral tibial spine, and increased obliquity of the tibial plateau.26 They did not find statistically significant increased squaring of the lateral femoral condyle or cupping of the lateral tibial plateau. Radiographic signs can be subtle and may not all be present in a patient with a discoid meniscus.

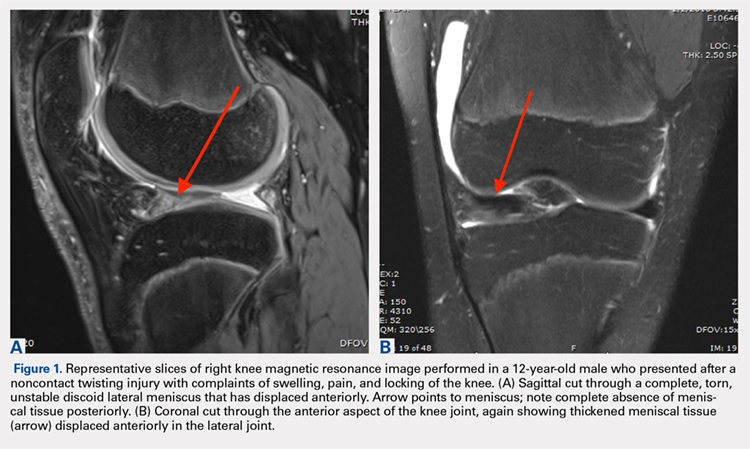

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the assessment technique of choice for the diagnosis of discoid meniscus, although MRI may not reliably identify a Wrisberg variant or incomplete discoid menisci (Figure 1).

Gans and colleagues27 examined preoperative MRI and clinical examination compared with pathology found during arthroscopy. Although they found that MRI and clinical examination had excellent diagnostic accuracy of 92.7% and 95.3%, respectively, the most common missed pathology on MRI later found on diagnostic arthroscopy was the presence of a lateral discoid meniscus, which occurred in 26.7% of missed diagnoses. Adult diagnostic criteria of discoid meniscus include ≥3 contiguous 5-mm sagittal cuts showing continuity between the anterior and posterior horns of the meniscus. Other criteria include a minimal meniscal width >15 mm on the coronal view or a minimum meniscal width that is >20% of the width of the maximal tibial width.28 These criteria are often applied to children as well. Additionally, if >50% of the lateral joint space is covered by meniscal tissue, a diagnosis of discoid meniscus should be considered.6

Continue to: TREATMENT