The liability climate for Kentucky physicians has long been bleak, according to Bruce A. Scott, MD, president of the Kentucky Medical Association. Insurance premiums are high, few doctors want to relocate to the Bluegrass State, and an overriding fear of lawsuits weighs heavily on the minds of physicians practicing there.

So the physician community was encouraged when in 2017, Kentucky enacted a law requiring all new malpractice claims to go before a medical review panel. The panel, comprised of an attorney and three health care professionals, would review evidence and opine on whether defendants had breached the standard of care. Plaintiffs could then decide whether to drop or resolve the case, or whether to continue to court.

“We saw it as a modest step forward,” Dr. Scott said in an interview. “[The panel] was hopefully going to speed up justice. Those cases that had merit would be settled, and those cases that didn’t have merit would be eliminated to allow the trial court to move on to the cases that needed to be tried.”

The Kentucky Supreme Court disagreed. In November 2018, state justices struck down the panel law as unconstitutional. Requiring plaintiffs to go before a medical review panel delays access to the courts and impedes their right to a speedy trial, the court ruled.

The end to Kentucky’s short-lived medical review panel raises questions about whether such advisory committees are beneficial in medical liability cases. Do review panels help reduce frivolous claims? What effects do the panels have on case duration and court costs?

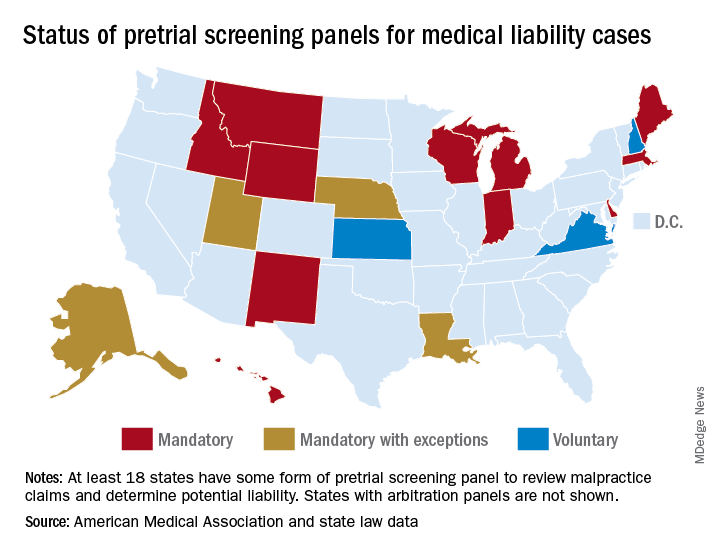

At least 17 states have some form of pretrial screening panel that evaluates claims against health care professionals. Most panels include legal experts and medical professionals who review evidence and make a determination about potential negligence. In some states, such as Indiana, a panel review is mandatory, whereas in others, like Kansas, the process is voluntary.* Most panel decisions are nonbinding, and parties can proceed to court if they prefer.

Maine: A success story

Maine has experienced marked success with its medical review panel, which has been active since 1986, said Andrew B. MacLean, an attorney and interim CEO for the Maine Medical Association (MMA). The three-person panel, which includes a judicial expert, an attorney, and a physician, addresses whether the defendant’s actions constitute a deviation from the standard of care, whether acts or omissions caused the alleged injury, and the degree to which potential negligence exists on the part of the health care professional and/or the patient.

“The vast majority of medical malpractice claims in Maine are resolved at or before the screening panel stage and our state’s relatively small medical malpractice bar has come to accept this and to work cooperatively within the panel process,” Mr. MacLean said in an interview. “This has not been easy, but we’ve achieved such a result through many years of negotiation among representatives of the judiciary, plaintiffs’ and defense bar, professional liability insurers, and the professional organizations of trial lawyers and physicians.”

From 1986 to 2002, pretrial panels in Maine analyzed 242 medical liability cases, according to MMA data. Panelists found unanimously for the defendant in 157 cases and unanimously for the plaintiff in 42. In 43 cases, panelists were split. Of the total 242 cases, 151 were ultimately dismissed, 61 cases were settled, and 30 cases went to trial. Of the 30 cases that went to trial, jurors found for the health care professional 26 times.

A medical panel review is a quicker way to determine liability, and the process generally benefits both parties, said Peter Michaud, MMA associate general counsel. Panel hearings last 1-2 days, whereas court trial can take weeks, said Mr. Michaud, who chaired Maine’s panel for 10 years. At the same time, the patient gets their “day in court” and a chance to share their side of the story, he added.