• What are common clinical presentations of RCC?

Most patients are asymptomatic until the disease becomes advanced. The classic triad of flank pain, hematuria, and palpable abdominal mass is seen in approximately 10% of patients with RCC, partly because of earlier detection of renal masses by imaging performed for other purposes.10 Less frequently, patients present with signs or symptoms of metastatic disease such as bone pain or fracture (as seen in the case patient), painful adenopathy, and pulmonary symptoms related to mediastinal masses. Fever, weight loss, anemia, and/or varicocele often occur in young patients (≤ 46 years) and may indicate the presence of a hereditary form of the disease. Patients may present with paraneoplastic syndromes seen as abnormalities on routine blood work. These can include polycythemia or elevated liver function tests (LFTs) without the presence of liver metastases (known as Stauffer syndrome), which can be seen in localized renal tumors. Nearly half (45%) of patients present with localized disease, 25% present with locally advanced disease, and 30% present with metastatic disease.11 Bone is the second most common site of distant metastatic spread (following lung) in patients with advanced RCC.

• What is the approach to initial evaluation for a patient with suspected RCC?

Initial evaluation consists of a physical exam, laboratory tests including complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel (calcium, serum creatinine, LFTs, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], and urinalysis), and imaging. Imaging studies include computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and chest imaging. A chest radiograph may be obtained, although a chest CT is more sensitive for the presence of pulmonary metastases. MRI can be used in patients with renal dysfunction to evaluate the renal vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) for thrombus or to determine the presence of local invasion.12 Although bone and brain are common sites for metastases, routine imaging is not indicated unless the patient is symptomatic. The value of positron emission tomography in RCC remains undetermined at this time.

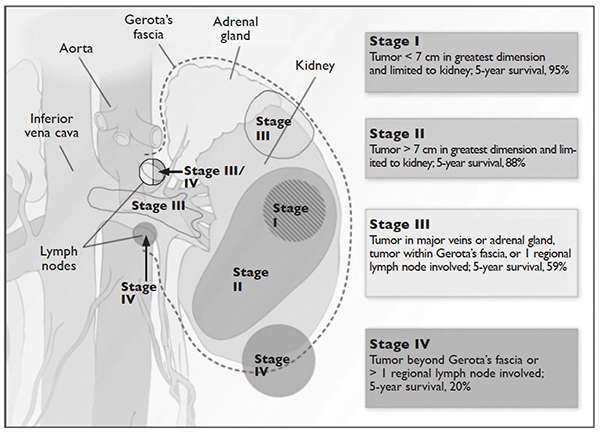

Staging is done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging classification for RCC; the Figure summarizes the staging and 5-year survival data based on this classification scheme.4,13

LIMITED-STAGE DISEASE

• What are the therapeutic options for limited-stage disease?

For patients with nondistant metastases, or limited-stage disease, surgical intervention with curative intent is considered. Convention suggests considering definitive surgery for patients with stage I and II disease, select patients with stage III disease with pathologically enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes, patients with IVC and/or cardiac atrium involvement of tumor thrombus, and patients with direct extension of the renal tumor into the ipsilateral adrenal gland if there is no evidence of distant disease. While there may be a role for aggressive surgical intervention in patients with distant metastatic disease, this topic will not be covered in this review.

SURGICAL INTERVENTION

Once patients are determined to be appropriate candidates for surgical removal of a renal tumor, the urologist will perform either a radical nephrectomy or a nephron-sparing nephrectomy, also called a partial nephrectomy. The urologist will evaluate the patient based on his or her body habitus, the location of the tumor, whether multiple tumors in one kidney or bilateral tumors are present, whether the patient has a solitary kidney or otherwise impaired kidney function, and whether the patient has a history of a hereditary syndrome involving kidney cancer as this affects the risk of future kidney tumors.

A radical nephrectomy is surgically preferred in the presence of the following factors: tumor larger than 7 cm in diameter, a more centrally located tumor, suspicion of lymph node involvement, tumor involvement with renal vein or IVC, and/or direct extension of the tumor into the ipsilateral adrenal gland. Nephrectomy involves ligation of the vascular supply (renal artery and vein) followed by removal of the kidney and surrounding Gerota’s fascia. The ipsilateral adrenal gland is removed if there is a high-risk for or presence of invasion of the adrenal gland. Removal of the adrenal gland is not standard since the literature demonstrates there is less than a 10% chance of solitary, ipsilateral adrenal gland involvement of tumor at the time of nephrectomy in the absence of high-risk features, and a recent systematic review suggests that the chance may be as low as 1.8%.14 Preoperative factors that correlated with adrenal involvement included upper pole kidney location, renal vein thrombosis, higher T stage (T3a and greater), multifocal tumors, and evidence for distant metastases or lymph node involvement. Lymphadenectomy previously had been included in radical nephrectomy but now is performed selectively. Radical nephrectomy may be performed as