.

The updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children, published in the Feb. 15 edition of Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085), address changes in management and diagnosis of the infection, and include recommendations for pediatric infection. The guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America were lasted published in 2010.

One of the strongest recommendations was on the use of FMTs to treat recurrent C. difficile infection after the failure of antibiotic therapy.

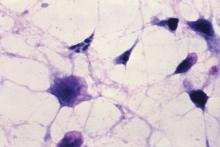

Courtesy CDC/Dr. Gilda Jones

Courtesy CDC/Dr. Gilda Jones

The Clostridium difficile enterotoxin, CPE, is the principal toxin involved in C. difficile foodborne illness. C. difficile is a spore forming bacteria which can be part of the normal intestinal flora in as many as 50% of children under age two. C. difficiCourtesy CDC/Dr. Gilda Jones

“Anecdotal treatment success rates of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent CDI [C. difficile infection] have been high regardless of route of instillation of feces, and have ranged between 77% and 94% with administration via the proximal small bowel; the highest success rates (80%-100%) have been associated with instillation of feces via the colon,” they wrote.

The guidelines also addressed what the authors described as the “evolving controversy” over the best methods for diagnosis, pointing out that there is little consensus about the best laboratory testing method.

“Given these various conundrums and the paucity of large prospective studies, the recommendations, while strong in some instances, are based upon a very low to low quality of evidence,” the authors said.

That aside, they advised that patients with unexplained and new-onset diarrhea (three or more unformed stools in 24 hours) were the preferred target population for testing for C. difficile infection. The most sensitive method of diagnosis in patients with clinical symptoms likely to be C. difficile infection was a nucleic acid amplification test, or a multistep algorithm, rather than a toxin test alone.

The guidelines committee also strongly advised against repeat testing within 7 days during the same episode of diarrhea, and against testing stool from asymptomatic patients, except for the purpose of epidemiologic study. They also noted there was insufficient evidence for the use of biologic markers such as fecal lactoferrin as an adjunct to testing.

The guidelines’ authors found there was not enough evidence to recommend discontinuing proton pump inhibitors to reduce the incidence of C. difficile infection, despite epidemiologic evidence of an association between proton pump inhibitor use and C. difficile infection. Similarly, there was a lack of evidence for the use of probiotics for primary prevention, but the authors noted that meta-analyses suggest probiotics may help prevent C. difficile infection in patients on antibiotics without a history of C. difficile infection.

With respect to antibiotic treatment, they recommended that patients diagnosed with C. difficile infection should first discontinue the inciting antibiotic treatment and then begin therapy with either vancomycin or fidaxomicin. For recurrent infection, they advised a tapered and pulsed regimen of oral vancomycin or a 10-day course of fidaxomicin. If patients had received metronidazole for the primary episode, they should be given a standard 10-day course of vancomycin for recurrent infection, the authors said.

In terms of diagnosis and management of pediatric C. difficile, the guidelines advised against routinely testing infants under 2 years of age with diarrhea, as the rate of C. difficile colonization even among asymptomatic infants can be higher than 40%. Even in children older than age 2, there was only a “weak” recommendation for C. difficile testing in patients with prolonged or worsening diarrhea and other risk factors such as inflammatory bowel disease or recent antibiotic exposure.

Children with a first episode or first recurrence of nonsevere C. difficile should be treated with either metronidazole or vancomycin, the authors wrote, but in the case of more severe illness or second recurrence, oral vancomycin was preferred over metronidazole.

The authors also suggested clinicians consider FMTs for children with recurrent infection that had failed to respond to antibiotics, but noted the quality of evidence for this was very low.

The guidelines were funded by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Six authors declared grants, consultancies, board positions, and other payments from the pharmaceutical industry outside the submitted work. One author also held patents relating to the treatment and prevention of C. difficile infection.

SOURCE: McDonald CL et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Feb 15. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085.