, new research shows. Results of a retrospective study show that of almost 4,500 patients with COVID-19, 12% were diagnosed with TME. Of these, 78% developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission. Septic encephalopathy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and uremia were the most common causes, although multiple causes were present in close to 80% of patients. TME was also associated with a 24% higher risk of in-hospital death.

“We found that close to one in eight patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had TME that was not attributed to the effects of sedatives, and that this is incredibly common among these patients who are critically ill” said lead author Jennifer A. Frontera, MD, New York University.

“The general principle of our findings is to be more aggressive in TME; and from a neurologist perspective, the way to do this is to eliminate the effects of sedation, which is a confounder,” she said.

The study was published online March 16 in Neurocritical Care.

Drilling down

“Many neurological complications of COVID-19 are sequelae of severe illness or secondary effects of multisystem organ failure, but our previous work identified TME as the most common neurological complication,” Dr. Frontera said.

Previous research investigating encephalopathy among patients with COVID-19 included patients who may have been sedated or have had a positive Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) result.

“A lot of the delirium literature is effectively heterogeneous because there are a number of patients who are on sedative medication that, if you could turn it off, these patients would return to normal. Some may have underlying neurological issues that can be addressed, but you can›t get to the bottom of this unless you turn off the sedation,” Dr. Frontera noted.

“We wanted to be specific and try to drill down to see what the underlying cause of the encephalopathy was,” she said.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data on 4,491 patients (≥ 18 years old) with COVID-19 who were admitted to four New York City hospitals between March 1, 2020, and May 20, 2020. Of these, 559 (12%) with TME were compared with 3,932 patients without TME.

The researchers looked at index admissions and included patients who had:

- New changes in mental status or significant worsening of mental status (in patients with baseline abnormal mental status).

- Hyperglycemia or with transient focal neurologic deficits that resolved with glucose correction.

- An adequate washout of sedating medications (when relevant) prior to mental status assessment.

Potential etiologies included electrolyte abnormalities, organ failure, hypertensive encephalopathy, sepsis or active infection, fever, nutritional deficiency, and environmental injury.

Foreign environment

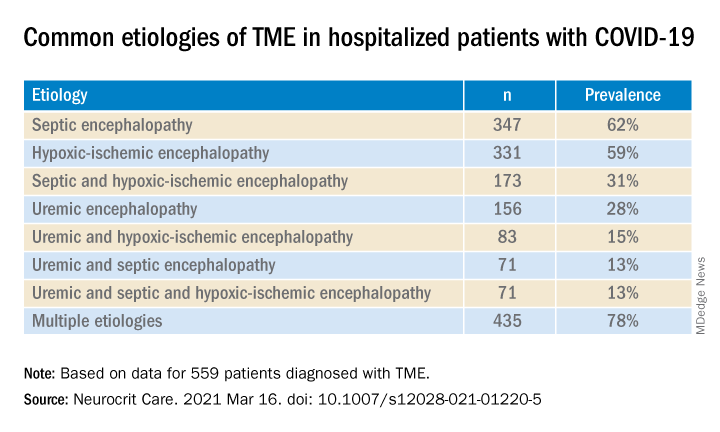

Most (78%) of the 559 patients diagnosed with TME had already developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission, the authors report. The most common etiologies of TME among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are listed below.

Compared with patients without TME, those with TME – (all Ps < .001):

- Were older (76 vs. 62 years).

- Had higher rates of dementia (27% vs. 3%).

- Had higher rates of psychiatric history (20% vs. 10%).

- Were more often intubated (37% vs. 20%).

- Had a longer length of hospital stay (7.9 vs. 6.0 days).

- Were less often discharged home (25% vs. 66%).

“It’s no surprise that older patients and people with dementia or psychiatric illness are predisposed to becoming encephalopathic,” said Dr. Frontera. “Being in a foreign environment, such as a hospital, or being sleep-deprived in the ICU is likely to make them more confused during their hospital stay.”

Delirium as a symptom

In-hospital mortality or discharge to hospice was considerably higher in the TME versus non-TME patients (44% vs. 18%, respectively).

When the researchers adjusted for confounders (age, sex, race, worse Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score during hospitalization, ventilator status, study week, hospital location, and ICU care level) and excluded patients receiving only comfort care, they found that TME was associated with a 24% increased risk of in-hospital death (30% in patients with TME vs. 16% in those without TME).

The highest mortality risk was associated with hypoxemia, with 42% of patients with HIE dying during hospitalization, compared with 16% of patients without HIE (adjusted hazard ratio 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.00; P = .001).

“Not all patients who are intubated require sedation, but there’s generally a lot of hesitation in reducing or stopping sedation in some patients,” Dr. Frontera observed.

She acknowledged there are “many extremely sick patients whom you can’t ventilate without sedation.”

Nevertheless, “delirium in and of itself does not cause death. It’s a symptom, not a disease, and we have to figure out what causes it. Delirium might not need to be sedated, and it’s more important to see what the causal problem is.”

Independent predictor of death

Commenting on the study, Panayiotis N. Varelas, MD, PhD, vice president of the Neurocritical Care Society, said the study “approached the TME issue better than previously, namely allowing time for sedatives to wear off to have a better sample of patients with this syndrome.”

Dr. Varelas, who is chairman of the department of neurology and professor of neurology at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, emphasized that TME “is not benign and, in patients with COVID-19, it is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality.”

“One should take all possible measures … to avoid desaturation and hypotensive episodes and also aggressively treat SAE and uremic encephalopathy in hopes of improving the outcomes,” added Dr. Varelas, who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting on the study, Mitchell Elkind, MD, professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University in New York, who was not associated with the research, said it “nicely distinguishes among the different causes of encephalopathy, including sepsis, hypoxia, and kidney failure … emphasizing just how sick these patients are.”

The study received no direct funding. Individual investigators were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The investigators, Dr. Varelas, and Dr. Elkind have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.