Results

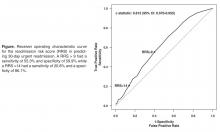

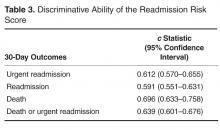

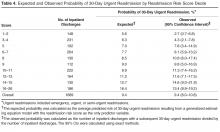

There were 1689 hospital inpatient discharges for 1515 patients during the study period. In this population, the mean age was 64 ± 17 years, 50% were female, and 87% were Caucasian. Additional characteristics are reported in Table 2 . Of the 1689 hospital inpatient discharges, 159 (9.4%) resulted in a 30-day urgent readmission and 190 (11.2%) resulted in any 30-day readmission. Among the 1515 patients, 57 (3.8%) died within 30 days of discharge.The RRS was significantly associated with 30-day urgent readmission (odds ratio [OR] for 1-point increase in the RRS, 1.07 [95% confidence interval {CI} 1.05–1.10]; P < 0.001). A c statistic of 0.612 (95% CI 0.570–0.655) indicates that the RRS has some ability to discriminate between those with and without a 30-day urgent readmission ( Figure, Table 3 ). The expected and observed probabilities of 30-day urgent readmission were similar in each decile of the RRS. The calibration ( Table 4 ) shows that although there is some deviation between the observed and expected probabilities,

the calibration is fairly good, particularly at the higher risk levels, making the tool more valuable for the high-risk patients.The RRS was also significantly associated with each of the secondary outcome measures. The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the RRS for any 30-day readmission was 1.06 (95% CI 1.03–1.09, P < 0.001) and the c statistic was 0.591 (95% CI 0.551–0.631, Table 2). The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the

RRS for 30-day death was 1.13 (95% CI 1.08–1.18, P < 0.001) and the c statistic was 0.696 (95% CI 0.633–0.758, Table 2). The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the RRS for 30-day death or 30-day urgent readmission was 1.09 (95% CI 1.07–1.12, P < 0.001) and the c statistic was 0.639 (95% CI 0.601–0.676, Table 2).Discussion

Our study provides evidence that the RRS has some ability to discriminate between patients who did and did not have a 30-day urgent readmission (c statistic 0.612 [95% CI 0.570–0.655]). More importantly the calibration appears to be good particularly in the higher risk patients, which are the most crucial to identify in order to target interventions.

In addition to predicting the risk of readmission, our method of risk evaluation has several other advantages. First, the risk score is assigned to each patient within 24 to 48 hours of admission by using elements available at the time of, or soon after, admission. This early evaluation during the hospitalization identifies patients who could benefit from interventions throughout the stay that could help mitigate the risks and allow for a safer transition. Other studies have used elements available only at discharge, such as lab values and length of stay [7,11]. Donze et al used 7 elements in a validated scoring system, but several of the elements were discharge values and the risk assessment system had a fair discriminatory value with a c statistic of 0.71, similar to our results. The advantage to having the score available at admission is that several of the factors used to compose the RRS could be addressed during the hospitalization, including increased education for those with greater than 7 medications, intensive care management intervention for those with a lack of social support, and increased or modified education for those with low health literacy.