Persistent Infection. Persistent H. pylori infection, due either to initial false-negative testing or ongoing infection despite first-line therapy, is another cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease.1,15 Because antibiotics and PPIs can reduce the number of H. pylori bacteria, use of these medications concurrent with H. pylori testing can lead to false-negative results with several testing modalities. When suspicion for H. pylori is high, 2 or more diagnostic tests may be needed to effectively rule out infection.15

When H. pylori is detected, successful eradication is becoming more difficult due to an increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance, leading to persistent infection in many cases and maintained risk of peptic ulcer disease, despite appropriate first-line therapy.8 Options for salvage therapy for persistent H. pylori, as well as information on the role and best timing of susceptibility testing, are beyond the scope of this review, but are reviewed by Lanas and Chan1 and in the American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the treatment of H. pylori infection.8

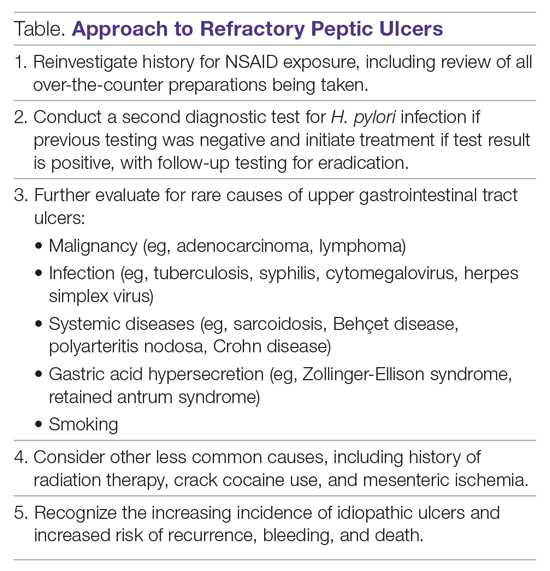

Other Causes. In a meta-analysis of rigorously designed studies from North America, 20% of patients experienced ulcer recurrence at 6 months, despite successful H. pylori eradication and no NSAID use.20 In addition, as H. pylori prevalence is decreasing, idiopathic ulcers are increasingly being diagnosed, and such ulcers may be associated with high rates of GIB and mortality.1 In this subset of patients with non-H. pylori, non-NSAID ulcers, increased effort is required to further evaluate the differential diagnosis for rarer causes of upper GI tract ulcer disease (Table). Certain malignancies, including adenocarcinoma and lymphoma, can cause ulcer formation and should be considered in refractory cases. Repeat biopsy at follow-up endoscopy for persistent ulcers should always be obtained to further evaluate for malignancy.1,15 Infectious diseases other than H. pylori infection, such as tuberculosis, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus, are also reported as etiologies of refractory ulcers, and require specific antimicrobial treatment over and above PPI monotherapy. Special attention in biopsy sampling and sample processing is often required when infectious etiologies are being considered, as specific histologic stains and cultures may be needed for identification.15

Systemic conditions, including sarcoidosis,21 Behçet disease,22 and polyarteritis nodosa,15,23 can also cause refractory ulcers. Approximately 15% of patients with Crohn disease have gastroduodenal involvement, which may include ulcers of variable sizes.1,15,24 The increased gastric acid production seen in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome commonly presents as refractory peptic ulcers in the duodenum beyond the bulb that do not heal with standard doses of PPIs.1,15 More rare causes of acid hypersecretion leading to refractory ulcers include idiopathic gastric acid hypersecretion and retained gastric antrum syndrome after partial gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis.15 Smoking is a known risk factor for impaired tissue healing throughout the body, and can contribute to impaired healing of peptic ulcers through decreased prostaglandin synthesis25 and reduced gastric mucosal blood flow.26 Smoking should always be addressed in patients with refractory peptic ulcers, and cessation should be strongly encouraged. Other less common causes of refractory upper GI tract ulcers include radiation therapy, crack cocaine use, and mesenteric ischemia.15

Managing Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications

Use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants, alone or in combination, increases the risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. In patients who continue to take aspirin after a peptic ulcer bleed, recurrent bleeding occurs in up to 300 cases per 1000 person-years. The rate of GIB associated with aspirin use ranges from 1.1% to 2.5%, depending on the dose. Prior peptic ulcer disease, age greater than 70 years, and concurrent NSAID, steroid, anticoagulant, or dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) use increase the risk of bleeding while on aspirin. The rate of GIB while taking a thienopyridine alone is slightly less than that when taking aspirin, ranging from 0.5% to 1.6%. Studies to date have yielded mixed estimates of the effect of DAPT on the risk of GIB. Estimates of the risk of GIB with DAPT range from an odds ratio for serious GIB of 7.4 to an absolute risk increase of only 1.3% when compared to clopidogrel alone.27

Many patients are also on warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC). In a study from the United Kingdom, the adjusted rate ratio of GIB with warfarin alone was 1.94, and this increased to 6.48 when warfarin was used with aspirin.28 The use of warfarin and DAPT, often called triple therapy, further increases the risk of GIB, with a hazard ratio of 5.0 compared to DAPT alone, and 5.38 when compared to warfarin alone. DOACs are increasingly prescribed for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolism, and by 2014 were prescribed as often as warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation in the United States. A meta-analysis showed the risk of major GIB did not differ between DOACs and warfarin or low-molecular-weight heparin, but among DOACs factor Xa inhibitors showed a reduced risk of GIB compared with dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor.29

The use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants in the context of peptic ulcer bleeding is a current management challenge. Data to guide decision-making in patients on antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy who experience peptic ulcer bleeding are scarce. Decision-making in this group of patients requires balancing the severity and risk of bleeding with the risk of thromboembolism.1,27 In patients on antiplatelet therapy for primary prophylaxis of atherothrombosis who develop bleeding from a peptic ulcer, the antiplatelet should generally be held and the indication for the medication reassessed. In patients on antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention, the agent may be immediately resumed after endoscopy if bleeding is found to be due to an ulcer with low-risk stigmata. With bleeding resulting from an ulcer with high-risk stigmata, antiplatelet agents employed for secondary prevention may be held initially, with consideration given to early reintroduction, as early as day 3 after endoscopy.1 In patients at high risk for atherothrombotic events, including those on aspirin for secondary prophylaxis, withholding aspirin leads to a 3-fold increase in the risk of a major adverse cardiac event, with events occurring as early as 5 days after aspirin cessation in some cases.27 A randomized controlled trial of continuing low-dose aspirin versus withholding it for 8 weeks in patients on aspirin for secondary prophylaxis of cardiovascular events who experienced peptic ulcer bleeding that required endoscopic therapy demonstrated lower all-cause mortality (1.3% vs 12.9%), including death from cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events, among those who continued aspirin therapy, with a small increased risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding (10.3% vs 5.4%).30 Thus, it is recommended that antiplatelet therapy, when held, be resumed as early as possible when the risk of a cardiovascular or cerebrovascular event is considered to be higher than the risk of bleeding.27

When patients are on DAPT for a history of drug-eluting stent placement, withholding both antiplatelet medications should be avoided, even for a brief period of time, given the risk of in-stent thrombosis. When DAPT is employed for other reasons, it should be continued, if indicated, after bleeding that is found to be due to peptic ulcers with low-risk stigmata. If bleeding is due to a peptic ulcer with high-risk stigmata at endoscopy, then aspirin monotherapy should be continued and consultation should be obtained with a cardiologist to determine optimal timing to resume the second antiplatelet agent.1 In patients on anticoagulants, anticoagulation should be resumed once hemostasis is achieved when the risk of withholding anticoagulation is thought to be greater than the risk of rebleeding. For example, anticoagulation should be resumed early in a patient with a mechanical heart valve to prevent thrombosis.1,27 Following upper GIB from peptic ulcer disease, patients who will require long-term aspirin, DAPT, or anticoagulation with either warfarin or DOACs should be maintained on long-term PPI therapy to reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding.9,27