Failure of Endoscopic Therapy to Control Peptic Ulcer Bleeding

Bleeding recurs in as many as 10% to 20% of patients after initial endoscopic control of peptic ulcer bleeding.4,31 In this context, repeat upper endoscopy for hemostasis is preferred to surgery, as it leads to less morbidity while providing long-term control of bleeding in more than 70% of cases.31,32 Two potential endoscopic rescue therapies that may be employed are over-the-scope clips (OTSCs) and hemostatic powder.32,33

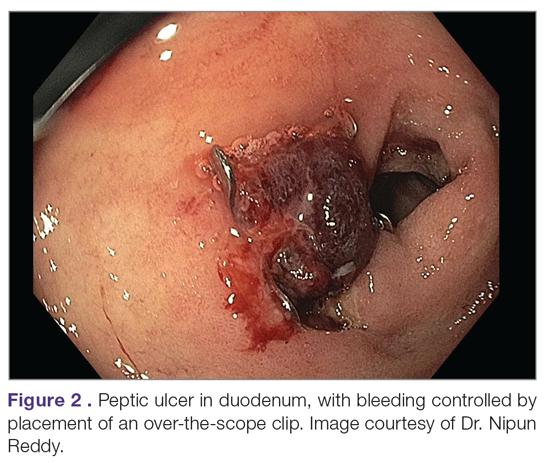

While through-the-scope (TTS) hemostatic clips are often used during endoscopy to control active peptic ulcer bleeding, their use may be limited in large or fibrotic ulcers due to the smaller size of the clips and method of application. OTSCs have several advantages over TTS clips; notably, their larger size allows the endoscopist to achieve deeper mucosal or submucosal clip attachment via suction of the targeted tissue into the endoscopic cap (Figure 2). In a systematic review of OTSCs, successful hemostasis was achieved in 84% of 761 lesions, including 75% of lesions due to peptic ulcer disease.34 Some have argued that OTSCs may be preferred as first-line therapy over epinephrine with TTS clips for hemostasis in bleeding from high-risk peptic ulcers (ie, those with visualized arterial bleeding or a visible vessel) given observed decreases in rebleeding events.35

Despite the advantages of OTSCs, endoscopists should be mindful of the potential complications of OTSC use, including luminal obstruction, particularly in the duodenum, and perforation, which occurs in 0.3% to 2% of cases. Additionally, retrieval of misplaced OTSCs presents a significant challenge. Careful decision-making with consideration of the location, size, and depth of lesions is required when deciding on OTSC placement.34,36

A newer endoscopic tool developed for refractory bleeding from peptic ulcers and other causes is hemostatic powder. Hemostatic powders accelerate the coagulation cascade, leading to shortened coagulation times and enhanced clot formation.37 A recent meta-analysis showed that immediate hemostasis could be achieved in 95% of cases of bleeding, including in 96% of cases of bleeding from peptic ulcer disease.38 The primary limitation of hemostatic powders is the temporary nature of hemostasis, which requires the underlying etiology of bleeding to be addressed in order to provide long-term hemostasis. In the above meta-analysis, rebleeding occurred in 17% of cases after 30 days.38

Hypotension and ulcer diameter ≥ 2 cm are independent predictors of failure of endoscopic salvage therapy.31 When severe bleeding is not controlled with initial endoscopic therapy or bleeding recurs despite salvage endoscopic therapy, transcatheter angiographic embolization (TAE) is the treatment of choice.4 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that compared TAE to surgery have shown that the rate of rebleeding may be higher with TAE, but with less morbidity and either decreased or equivalent rates of mortality, with no increased need for additional interventions.4,32 In a case series examining 5 years of experience at a single medical center in China, massive GIB from duodenal ulcers was successfully treated with TAE in 27 of 29 cases (93% clinical success rate), with no mucosal ischemic necrosis observed.39

If repeated endoscopic therapy has not led to hemostasis of a bleeding peptic ulcer and TAE is not available, then surgery is the next best option. Bleeding gastric ulcers may be excised, wedge resected, or oversewn after an anterior gastrostomy. Bleeding duodenal ulcers may require use of a Kocher maneuver and linear incision of the anterior duodenum followed by ligation of the gastroduodenal artery. Fortunately, such surgical management is rarely necessary given the availability of TAE at most centers.4

Conclusion

Peptic ulcer disease is a common health problem globally, with persistent challenges related to refractory ulcers, antiplatelet and anticoagulant use, and continued bleeding in the face of endoscopic therapy. These challenges should be met with adequate frequency and duration of PPI therapy, vigilant attention to and treatment of ulcer etiology, evidence-based handling of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications, and utilization of novel endoscopic tools to obtain improved clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgment: We thank Dr. Nipun Reddy from our institution for providing the endoscopic images used in this article.

Corresponding author: Adam L. Edwards, MD, MS; aledwards@uabmc.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.