From the Editor

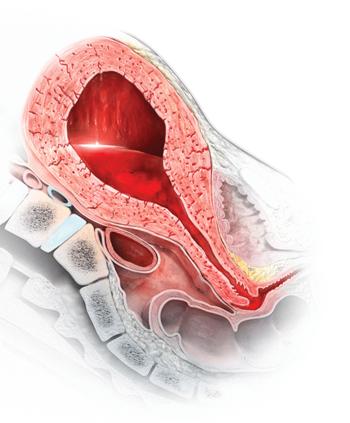

A stitch in time: The B-Lynch, Hayman, and Pereira uterine compression sutures

All three of these uterine compression sutures are effective at treating postpartum hemorrhage caused by uterine atony—remember to use them

Dr. Barbieri is Editor in Chief, OBG Management; Chair, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital; and Kate Macy Ladd Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Dr. Barbieri reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

For women who experience a postpartum hemorrhage, and already have received oxytocin as part of routine obstetric care, prioritize the use of parenteral uterotonics, including oxytocin, methylergonovine, and carboprost tromethamine, and avoid the use of rectal misoprostol

Uterine atony is failure of the uterus to contract following delivery and is a common cause of postpartum hemorrhage. The options for treating hemorrhage due to this cause are uterotonic agents, including additional oxytocin, carboprost tromethamine, methylergonovine, and misoprostol. Prioritizing the optimal therapy given the circumstances is imperative to maternal safety.

Most authorities recommend that, following delivery, all women should receive a uterotonic medication to reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).1 In the United States, the preferred uterotonic for this preventive effort is oxytocin—a low-cost, highly effective agent that typically is administered as an intravenous (IV) infusion or intramuscular (IM) injection. Unfortunately, even with the universal administration of oxytocin in the third stage of labor, PPH occurs in about 3% of vaginal deliveries.

A key decision in treating a PPH due to uterine atony is treatment with an optimal uterotonic. The options include:

Many obstetricians choose rectal misoprostol alone or in combination with oxytocin as the preferred treatment of PPH. However, evidence from clinical trials and pharmacokinetic studies suggest that rectal misoprostol is not an optimal choice if parenteral uterotonics are available. Here I pre-sent this evidence and urge you to stop the practice of using rectal misoprostol in efforts to manage PPH.

RCTs do not support the use of rectal misoprostolRandomized clinical trials (RCTs) have not demonstrated that misoprostol is superior to oxytocin for the treatment of PPH caused by uterine atony.2 For example, Blum and colleagues studied 31,055 women who received oxytocin (by IV or IM route) at vaginal delivery and observed that 809 (3%) developed a PPH.3 The women who developed PPH were randomly assigned to treatment with misoprostol 800 µg sublingual or oxytocin 40 U in 1,000 mL as an IV infusion over 15 minutes.

Both oxytocin and misoprostol had similar efficacy for controlling bleeding within 20 minutes (90% and 89%, respectively). Fewer women had blood loss of 1,000 mL or greater when treated with oxytocin compared with misoprostol (1% vs 3%, respectively; P = .062). In addition, oxytocin was associated with fewer temperature elevations of 38°C (100.4°F) or above (15% vs 22% for misoprostol, P = .007) and fewer temperature elevations of 40°C (104°F) or above (0.2% vs 1.2% for misoprostol, P = .11).

In another trial, women with a vaginal delivery who were not treated with a uterotonic in the third stage were monitored for the development of a PPH.4 PPH did develop in 1,422 women, who were then randomly assigned to receive oxytocin (10 U IV or IM) plus a placebo tablet or oxytocin plus misoprostol (600 µg sublingual).

Comparing oxytocin alone versus oxytocin plus misoprostol, there was no difference in blood loss of 500 mL or greater after treatment initiation (14% vs 14%). However, 90 minutes following treatment, temperature elevations occurred much more often in the women who received oxytocin plus misoprostol compared with the women who received oxytocin alone (temperature ≥38°C: 58% vs 19%; temperature ≥40°C: 6.8% vs 0.4%).

Bottom line: If you have access to oxytocin, there is no advantage to using misoprostol to treat a PPH due to uterine atony.5

Rectal misoprostol does not achieve optimal circulating concentrations of the drugMisoprostol tablets are formulated for oral administration, not rectal administration. The studies in the TABLE show that rectal administration of misoprostol results in lower circulating concentration of the medication compared to oral, buccal, or vaginal administration.6−8 After rectal administration it takes about 60 minutes to reach the peak circulating concentration of misoprostol.6,7 By contrast, parenteral oxytocin, methylergonovine, and carboprost tromethamine reach peak serum concentration much more quickly after administration.

In a study of misoprostol stimulation of uterine contractility as measured by an intrauterine pressure catheter, buccal administration resulted in higher peak uterine tone than rectal administration (49 vs 31 mm Hg).8 In addition, time to onset of uterine contractility was 41 minutes and 103 minutes, respectively, for buccal and rectal administration.

These studies show that rectal misoprostol is associated with lower serum concentrations, longer time to onset of uterine contraction, and less contractility than buccal administration. The one advantage of rectal administration is that it has a longer duration of action than the oral, buccal, or sublingual routes. In pharmacokinetic comparisons of buccal versus sublingual administration of misoprostol, the sublingual route results in greater peak concentration, which may cause more adverse effects.9,10

Worldwide, approximately one maternal death occurs every 7 minutes. Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a common cause of maternal death. Oxytocin, methylergonovine, and carboprost tromethamine should be stored in a refrigerated environment to ensure the stability and bioavailability of the drug. In settings in which reliable refrigeration is not available, misoprostol, a medication that is heat-stable, is often used to prevent and treat PPH.

One approach to preventing PPH is to provide 600 µg of misoprostol to women delivering at home without a skilled birth attendant that they can self- administer after the delivery.1,2 Another approach is to recommend that skilled birth attendants administer misoprostol following the delivery.3

Although I am recommending that we not use rectal misoprostol to treat PPH in the United States, it is clear that misoprostol plays an important role in preventing PPH in countries where parenteral uterotonics are not available. If a clinician in the United States was involved in a home birth complicated by PPH due to uterine atony, and if misoprostol was the only available uterotonic, it would be wise to administer it promptly.

References

All three of these uterine compression sutures are effective at treating postpartum hemorrhage caused by uterine atony—remember to use them

Administering the appropriate amount of oxytocin maximizes its benefits and minimizes its side effects. Regrettably, too little, too much or none...

Don’t waste valuable time waiting for coagulation studies to return from the lab—use your clinical judgment and start transfusing clotting factors...

Reach for the balloon often and, for greatest benefit, apply it early in the postpartum hemorrhage treatment algorithm