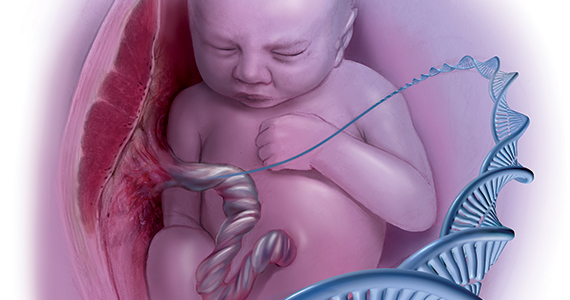

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common cause of severe neurodisability in children, and it occurs in about 2 to 3 per 1,000 births worldwide.1 This nonprogressive disorder is characterized by symptoms that include spasticity, dystonia, choreoathetosis, and/or ataxia that are evident in the first few years of life. While many perinatal variables have been associated with CP, in most cases a specific cause is not identified.

Other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as intellectual disability, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorder, are often associated with CP.2 These other neurodevelopmental disorders are often genetic, and this has raised the question as to whether CP also might have a substantial genetic component, although this has not been investigated in any significant way until recently. This topic is of great interest to the obstetric community, given that CP often is attributed to obstetric events, including mismanagement of labor and delivery.

Emerging evidence of a genetic-CP association

In an article published recently in JAMA, Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues sought to determine the diagnostic yield of exome sequencing for CP.3 This large cross-sectional study included results of exome sequencing performed in 2 settings. The first setting was a commercial laboratory in which samples were sent for analysis due to a diagnosis of CP, primarily in children (n = 1,345) with a median age of 8.8 years. A second cohort, recruited from a neurodevelopmental disorders clinic at Geisinger, included primarily adults (n = 181) with a median age of 41.9 years.

As is standard in exome sequencing, results were considered likely causative if they were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic based on criteria of the American College of Genetics and Genomics. In the laboratory group, 32.7% (440 of 1,345) had a genetic cause of the CP identified, while in the clinic group, 10.5% (19 of 181) had a genetic etiology found. Although most of the identified genetic variants were de novo (that is, they arose in the affected individual and were not clearly inherited), some were inherited from carrier parents.3

A number of other recent studies also have investigated genetic causes of CP and similarly have reported that a substantial number of cases are genetic. Several studies that performed chromosomal microarray analysis in individuals with CP found deleterious copy number variants in 10% to 31% of cases.4-6 Genomic variants detectable by exome sequencing have been reported in 15% to 20% of cases.3 In a recent study in Nature Genetics, researchers performed exome sequencing on 250 parent-child “trios” in which the child had CP, and they found that 14% of cases had an associated genetic variant that was thought to be causative.4 These studies all provide consistent evidence that a substantial proportion of CP cases are due to genetic causes.

Contributors to CP risk

Historically, CP was considered to occur largely as a result of perinatal anoxia. In 1862, the British orthopedic surgeon William John Little first reported an association between prematurity, asphyxia, difficult delivery, and CP in a paper presented to the Obstetrical Society of London.7 Subsequently, much effort has gone into the prevention of perinatal asphyxia and birth injury, although our ability to monitor fetal well-being remains limited. Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are nonspecific and can occur for many reasons other than fetal asphyxia. Studies of electronic fetal monitoring have found that continuous monitoring primarily leads to an increase in cesarean delivery with no decrease in CP or infant mortality.8

While some have attributed this to failure to accurately interpret the fetal heart rate tracing, it also may be because a substantial number of CP cases are due to genetic and other causes, and that very few in fact result from preventable intrapartum injury.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics agree that knowledge gaps preclude definitive determination that a given case of neonatal encephalopathy is attributable to an acute intrapartum event, and they provide criteria that must be fulfilled to establish a reasonable causal link between an intrapartum event and subsequent long-term neurologic disability.9 However, there continues to be a belief in the medical, scientific, and lay communities that birth asphyxia, secondary to adverse intrapartum events, is the leading cause of CP. A “brain-damaged infant” remains one of the most common malpractice claims, and birth injury one of the highest paid claims. Such claims generally allege that intrapartum asphyxia has caused long-term neurologic sequelae, including CP.

While it is true that prematurity, infection, hypoxia-ischemia, and pre- and perinatal stroke all have been implicated as contributing to CP risk, large population-based studies have shown that birth asphyxia accounts for less than 12% of CP cases.10 Specifically, recent data indicate that acute intrapartum hypoxia-ischemia occurs only in about 6% of CP cases. In other words, it does occur and may contribute to some cases, but this is likely a smaller percent than previously thought, and genetic factors now appear to be far more significant contributors.11

Continue to: Exploring a genetic etiology...