CASE 1 What procedures should accompany hysterectomy?

A.E., 44, mother of one, complains of heavy irregular bleeding with no sensation of a vaginal bulge. She has tried oral contraceptives, but they did not improve her bleeding pattern. She also has undergone dilatation and curettage and hysteroscopy (benign findings), also with no improvement.

Examination reveals a 9- to 10-week-size fibroid uterus, which is confirmed by ultrasonography. Pelvic support appears to be excellent.

After a discussion of the options, the patient elects to undergo vaginal hysterectomy. Are other procedures warranted?

Ask a gynecologic surgeon to name the most significant challenges he or she faces, and the answer is likely to include preventing pelvic organ prolapse after surgical intervention. Approximately one third of operations for pelvic organ prolapse involve patients whose prolapse has recurred after previous surgery.1 Although we have advanced our understanding of the anatomy of pelvic support and the pathophysiology of support defects, the various surgical strategies remain largely untested and unproven.

Even women with good pelvic support who are undergoing hysterectomy—like the patient described above—are vulnerable. One particular area of concern: the risk of enterocele or vaginal apical prolapse, or both, after hysterectomy. In this article, I describe a technique to reduce the risk of these defects after vaginal hysterectomy: high uterosacral suspension, or modified McCall culdoplasty.

Enterocele and apical prolapse do not always coexist

Enterocele and apical prolapse are distinct entities. The latter represents a deficiency in the level I supporting structures described by DeLancey2—primarily the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments (FIGURE 1). Enterocele, or peritoneocele, is a herniation of the cul-de-sac peritoneum, with or without intestinal contents. In women who have undergone hysterectomy, enterocele is usually caused by a lack of continuity of level II fibers, namely, the failure to approximate the pubocervical and rectovaginal connective tissues at the time of hysterectomy.3 Careful attention to the vaginal cuff and cul-de-sac at the time of hysterectomy is therefore imperative.

FIGURE 1 Three levels of support

The endopelvic fascia of a posthysterectomy patient divided into DeLancey’s biomechanical levels: level I—proximal suspension, level II—lateral attachment, and level III—distal fusion.

The McCall culdoplasty: 50 years “young”

In 1957, Milton McCall, MD, described a technique to manage the cul-de-sac at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.4 The McCall technique of posterior culdoplasty differs from other approaches by omitting dissection and excision of the hernia sac, or excess cul-de-sac peritoneum. The original McCall culdoplasty begins with the placement of several rows (average of 3) of nonabsorbable suture (“internal” McCall sutures), starting at the left uterosacral ligament about 2 cm above its cut edge, and proceeding across the redundant cul-de-sac to terminate in the right uterosacral ligament. Each subsequent row is placed superior to the first, by applying traction to the previously placed sutures.

Prior to the tying of these sutures, 3 “external” absorbable sutures are placed. These sutures incorporate posterior vaginal epithelium, each uterosacral ligament, and the contralateral vaginal epithelium in a mirror image of the first pass through the vagina. Again, several rows are placed, each more superior to the last, to move the newly created vaginal apex to the highest point on the uterosacral ligaments once all the sutures are tied.

Tying the internal sutures not only creates a firm, shelf-like midline structure, but obliterates the redundant cul-de-sac. The external sutures move the vaginal apex to the uterosacral bridge and are tied at the conclusion of the procedure (FIGURES 2 and 3).

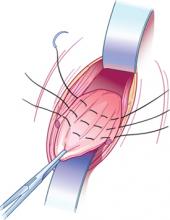

FIGURE 2 Internal McCall sutures

Traction on the most dependent portion of the cul-de-sac and posterior vaginal epithelium allows placement of 3 rows of sutures across the cul-de-sac from one uterosacral ligament to the other.

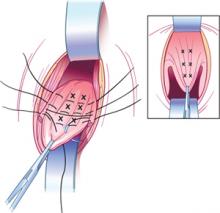

FIGURE 3 External McCall sutures

Three additional rows of absorbable sutures incorporate vaginal epithelium and uterosacral ligaments to move the vaginal cuff superiorly.

Modifications enhance durability and support

When the surgical indication is significant apical vaginal prolapse, the efficacy of the McCall procedure as both treatment and prevention is uncertain, because we lack adequate studies in this population. However, assuming that identifiable defects or breaks in the uterosacral ligaments lead to apical prolapse,3 use of the portion of the uterosacral ligament nearest the vagina appears unlikely to create a durable repair.