BOSTON – Many female physicians say that if they had to do it over again, they might have tried to have children sooner, chosen a different specialty, or elected to have embryos frozen "just in case" they had later fertility problems, an investigator said at the conjoint meeting of the International Federation of Fertility Societies and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Dr. Natalie A. Clark and her colleagues surveyed a random sample of female physicians in the United States to ask about their choices for timing of conception, their basic knowledge of reproductive limitations, and how reproductive choices factor into their professional and personal decision making. The investigators randomly selected 600 women who graduated from medical school from 1995 through 2000 from the American Medical Association (AMA) physicians’ database, and mailed surveys to them. A total of 333 (55.5%) responded.

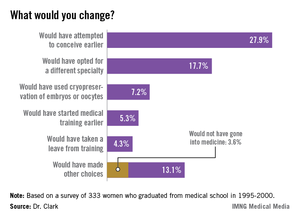

Asked whether they would in retrospect have changed anything about their reproductive choices, 27.9% said they would have attempted to conceive earlier, 17.7% would have opted for a different specialty, 7.2% would have used cryopreservation of embryos or oocytes, 5.3% would have started medical training earlier, and 4.3% would have taken a leave from training. Of the 13.1% who said they would have made other, unspecified choices, 3.6% independently reported that they would not have gone into medicine.

The survey of female physicians highlights the unique challenges that women of childbearing age face when trying to balance the demands of education, training, and career advancement, said Dr. Clark, a third-year resident at the University of Michigan department of obstetrics and gynecology in Ann Arbor.

"We have a number of highly educated patients who come into our clinic who have finished their MDs or PhDs, and have done a great amount of postgraduate work, and they present at very late reproductive ages. They say, "I’m ready to start reproducing, and I don’t want to be too aggressive, but what can I do?’ – not fully realizing that they’ve missed their ideal reproductive window," Dr. Clark said in an interview.

The majority of respondents (55%) work in specialties for women, children, and families, including family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, and pediatrics; 31% work in other medical specialties; 10% in hospital-based specialties; and 4% in surgical specialties.

In all, 80% of the respondents said they had attempted to conceive, and 77% had at least one biological child. The physicians on average had their first child 7.4 years later than did women in the general population, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

One-fourth (25%) of all respondents had been diagnosed with infertility. Ovulatory dysfunction was the most common cause, followed by male factor, age-related diminished ovarian reserve, endometriosis, tubal factor, and uterine factor.

"Despite having a medical background, 44% of infertile respondents were surprised about their diagnosis of infertility," Dr. Clark said. In every age range, physicians consistently underestimated their chances for conceiving, she added.

"I think that if we can change the culture of medicine such that we can support those decisions at a biologically advantageous time point, it could change the field of medicine," Dr. Clark said.

The study was supported by a grant from the AMA Joan F. Giambalvo Memorial Scholarship Fund. Dr. Clark was a 2012 recipient of a research award from the fund.