In 1978, Robert Neuwirth introduced loops to perform hysteroscopic myomectomy. The loop resectoscope was quickly followed by the rollerball to perform endometrial ablation. In the late 1990s, hysteroscopic bipolar cutting loops were introduced. This enabled use of ionic distension media saline, instead of nonionic media, thus decreasing risks related to hyponatremia.

In 2003, Mark Emanuel introduced hysteroscopic morcellation systems, which enabled more gynecologists to perform operative hysteroscopy safely. Resected tissue is removed immediately to allow superior visualization. The flexible hysteroscope coupled with vaginoscopy has enabled hysteroscopy to be done with minimal to no anesthesia in an in-office setting.

With advances in hysteroscopy over the past 35 years, hysteroscopic procedures such as polypectomy, myomectomy, lysis of adhesions, transection of endometriosis, evacuation of retained products of conception, and endometrial ablation/resection have become routine.

And now, the controversy

Since its inception, laparoscopic surgery has not been without controversy. In 1933, Karl Fervers described explosion and flashes of light from a combination of high frequency electric current and oxygen distension gas while performing laparoscopic adhesiolysis with the coagulation probe of the ureterocystoscope.

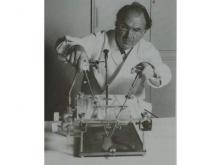

In the early 1970s, Professor Kurt Semm’s pioneering effort was not rewarded by his department, in Kiel, Germany, which instead recommended he schedule a brain scan and psychological testing.

Nearly 20 years later, in a 1992 edition of Current Science, Professor Semm, along with Alan DeCherney, stated that “over 80% of gynecological operations can now be performed by laparoscopy.” Shortly thereafter, however, Dr. Roy Pitkin, who at the time was president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, wrote an editorial in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology – “Operative Laparoscopy: Surgical Advance or Technical Gimmick?” (Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Mar;79[3]:441-2).

Fortunately, 18 years later, with the continued advances in laparoscopic surgery making it less expensive, safer, and more accessible, Dr. Pitkin did retract his statement (Obstet Gynecol. 2010 May;115[5]:890-1).

Currently, the gynecologic community is embroiled in controversies involving the use of the robot to assist in the performance of laparoscopic surgery, the incorporation of synthetic mesh to enhance urogynecologic procedures, the placement of Essure micro-inserts to occlude fallopian tubes, and the use of electronic power morcellation at time of laparoscopic or robot-assisted hysterectomy, myomectomy, or sacrocolpopexy.

After reading the 2013 article by Dr. Jason Wright, published in JAMA, comparing laparoscopic hysterectomy to robotic hysterectomy, no one can deny that the rise in a minimally invasive route to hysterectomy has coincided with the advent of the robot (JAMA. 2013 Feb 20;309[7]:689-98). On the other hand, many detractors, including Dr. James Breeden (past ACOG president 2012-2013), find the higher cost of robotic surgery very problematic. In fact, many of these detractors cite the paucity of data showing a significant advantage to use of robotics.

While certainly cost, more than ever, must be a major consideration, remember that during the 1990s, there were multiple articles in Ob.Gyn. News raising concerns about the cost of laparoscopic hysterectomy. Interestingly, studies over the past decade by Warren and Jonsdottir show a cost savings when hysterectomy is done laparoscopically as opposed to its being done by laparotomy. Thus, it certainly can be anticipated that with more physician experience, improved instrumentation, and robotic industry competition, the overall cost will become more comparable to a laparoscopic route.

In 1995, Ulf Ulmsten first described the use of tension-free tape (TVT) to treat stress urinary incontinence. In 1998, the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of the TVT sling in the United States. Since then, transobturator tension-free vaginal tape (TVT-O) and single incision mini-slings have been introduced. All of these techniques have been shown to be successful and have been well adapted into the armamentarium of physicians treating stress urinary incontinence.

With the success of synthetic mesh for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence, its use was extended to pelvic prolapse. In 2002, the first mesh device with indications for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse was approved by the FDA. While the erosion rate utilizing synthetic mesh for stress urinary incontinence has been noted to be 2%, rates up to 8.3% have been noted in patients treated for pelvic prolapse.

In 2008, the FDA issued a warning regarding the use of mesh for prolapse and incontinence repair secondary to the sequelae of mesh erosion. Subsequently, in 2011, the concern was limited to vaginal mesh to correct pelvic organ prolapse. Finally, on Jan. 4, 2016, the FDA issued an order to reclassify surgical mesh to repair pelvic organ prolapse from class II, which includes moderate-risk devices, to class III, which includes high-risk devices. Moreover, the FDA issued a second order to manufacturers to submit a premarket approval application to support the safety and effectiveness of synthetic mesh for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse.