Managing attempted pregnancy in the era of Zika virus

Oduyebo T, Igbinosa I, Petersen EE, et al. Update: interim guidance for health care providers caring for pregnant women with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, July 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(29):739-744.

Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, et al. Update: interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, September 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1077-1081.

US Food and Drug Administration. Donor Screening Recommendations to Reduce the Risk of Transmission of Zika Virus by Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/Tissue/UCM488582.pdf. Published March 2016. Accessed January 12, 2017.

National Institutes of Health. Zika: Overview. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/zika/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed January 12, 2017.

World Health Organization. Prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus interim guidance. WHO reference number: WHO/ZIKV/MOC/16. 1 Rev. 3, September 6, 2016.

Zika Virus Guidance Task Force of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Rev. 13, September 2016.

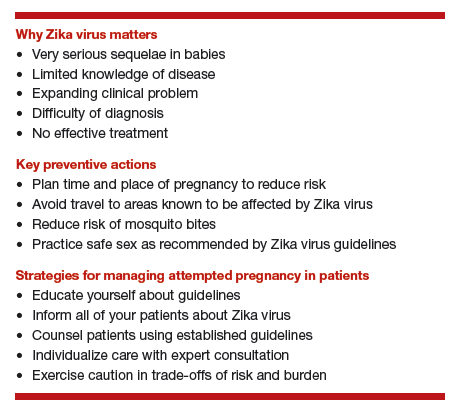

Zika virus presents unique challenges to physicians managing the care of patients attempting pregnancy, with or without fertility treatment. Neonatal Zika virus infection sequelae only recently have been appreciated; microcephaly was associated with Zika virus in October 2015, followed by other neurologic conditions including brain abnormalities, neural tube defects, and eye abnormalities. Results of recent studies involving the US Zika Pregnancy Registry show that 6% of women with Zika at any time in pregnancy had affected babies, but 11% of those who contracted the disease in the first trimester were affected.

Diagnosis is difficult because symptoms are generally mild, with 80% of affected patients asymptomatic. Possible Zika virus exposure is defined as travel to or residence in an area of active Zika virus transmission, or sex without a condom with a partner who traveled to or lived in an area of active transmission. Much is unknown about the interval from exposure to symptoms. Testing availability is limited and variable, and much is unknown about sensitivity and specificity of direct viral RNA testing, appearance and disappearance of detectable immunoglobulin (Ig) M and IgG antibodies that affect false positive and false negative test results, duration of infectious phase, risk of transmission, and numerous other factors.

Positive serum viral testing likely indicates virus in semen or other bodily fluids, but a negative serum viral test cannot definitively preclude virus in other bodily fluids. Zika virus likely can be passed from any combination of semen and vaginal and cervical fluids, but validating tests for these fluids are not yet available. It is not known if sperm preparation and assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures that minimize risk of HIV transmission are effective against Zika virus or whether or not cryopreservation can destroy the virus.

Pregnancy timing

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends that all men with possible Zika virus exposure who are considering attempting pregnancy with their partner wait to get pregnant until at least 6 months after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible Zika virus exposure (if asymptomatic). Women with possible Zika virus exposure are recommended to wait to get pregnant until at least 8 weeks after symptom onset (if symptomatic) or last possible Zika virus exposure (if asymptomatic).

Women and men with possible exposure to Zika virus but without clinical symptoms of illness should consider testing for Zika viral RNA within 2 weeks of suspected exposure and wait at least 8 weeks after the last date of exposure before being re-tested. If direct viral testing (using rRT-PCR) results initially are negative, ideally, antibody testing would be obtained, if available, at 8 weeks. However, no testing paradigm will absolutely guarantee lack of Zika virus infectivity.

Virus management problems are dramatically compounded in areas endemic for Zika. Women and men who have had Zika virus disease should wait at least 6 months after illness onset to attempt reproduction. The temporal relationship between the presence of viral RNA and infectivity is not known definitively, and so the absolute duration of time to wait before attempting pregnancy is unknown. Male and female partners who become infected should avoid all forms of intimate sexual conduct or use condoms for the same 6 months. There is no evidence Zika will cause congenital infection in pregnancies initiated after resolution of maternal Zika viremia. However, any testing performed at a time other than the time of treatment might not reflect true viral status, particularly in areas of active Zika virus transmission.

Prevention

Women and men, especially those residing in areas of active Zika virus transmission, should talk with their physicians regarding pregnancy plans and avoid mosquito bites using the usual precautions: avoid mosquito areas, drain standing water, use mosquito repellent containing DEET, and use mosquito netting. Some people have gone so far as to relocate to nonendemic areas.

Those contemplating pregnancy should be advised to consider what they would do if they become exposed to or have suspected or confirmed Zika virus during pregnancy. Additional considerations are gamete or embryo cryopreservation and quarantine until a subsequent rRT-PCR test result is negative in both the male and female and at least 8 weeks have passed from gamete collection.

Patient counseling essentials

Counsel patients considering reproduction about:

- Zika virus as a new reproductive hazard

- the significance of the hazard to the fetus if infected

- the areas of active transmission, and that they are constantly changing

- avoidance of Zika areas if possible

- methods of transmission through mosquito bites or sex

- avoidance of mosquito bites

- symptoms of Zika infection

- safe sex practices

- testing limitations and knowledge deficiency about Zika.

Not uncommonly, clinical situations require complex individualized management decisions regarding trade-offs of risks, especially in older patients with decreased ovarian reserve. Consultation with infectious disease and reproductive specialists should be obtained when complicated and consequential decisions have to be made.

All practitioners should inform their patients, especially those undergoing fertility treatments, about Zika, and develop language in their informed consent that conveys the gap in knowledge to these patients.

Read how obesity specifically affects reproduction in an adverse way